Baby Yoneda 3: Know Your Limits

Packaging Objects

In the previous article, we looked at virtual objects and their representations in more detail. The goal of today’s article will be to go through some of the most important examples of representable virtual objects - meets and joins.

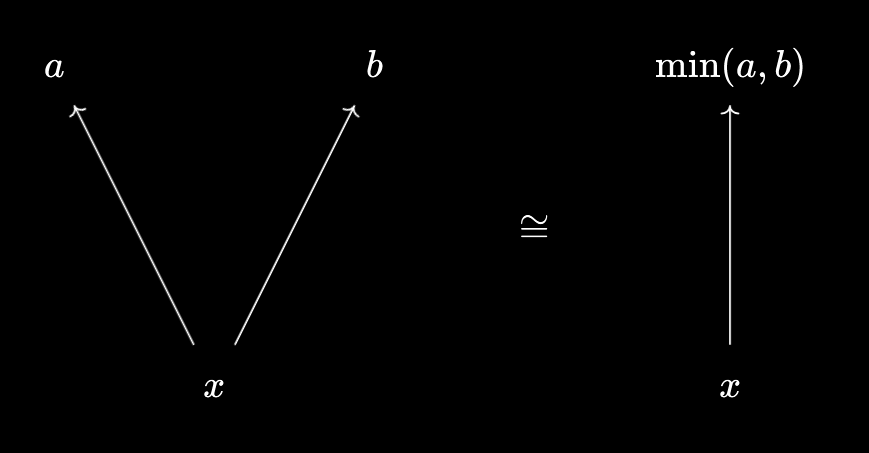

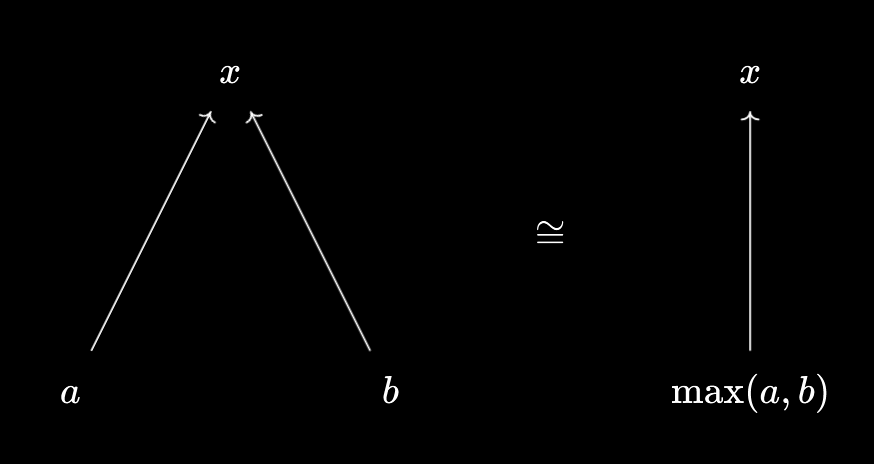

A lot of the content here naturally follows from Products, Categorically, but I’ll give a brief refresher. We can view lots of mathematical constructions as “packagers”, which simultaneously package/compress objects and relationships together. Good examples are min and max:

These illustrate the universal properties:

$x \leq \min(a, b) \iff x \leq a \text{ and } x \leq b$, $\max(a, b) \leq x \iff a \leq x \text{ and } b \leq x$.

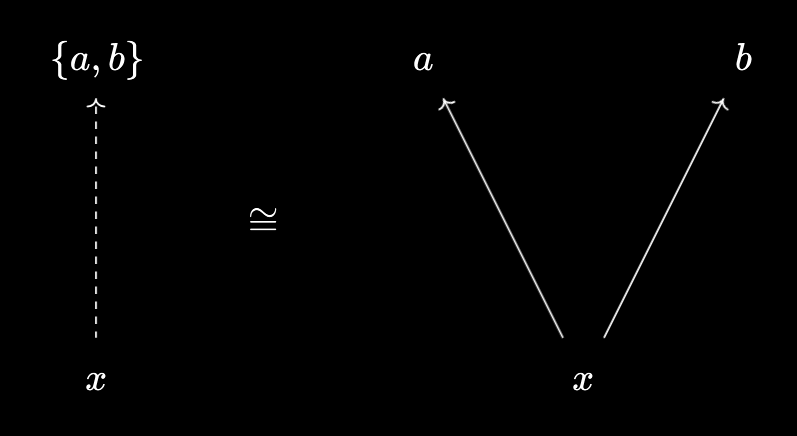

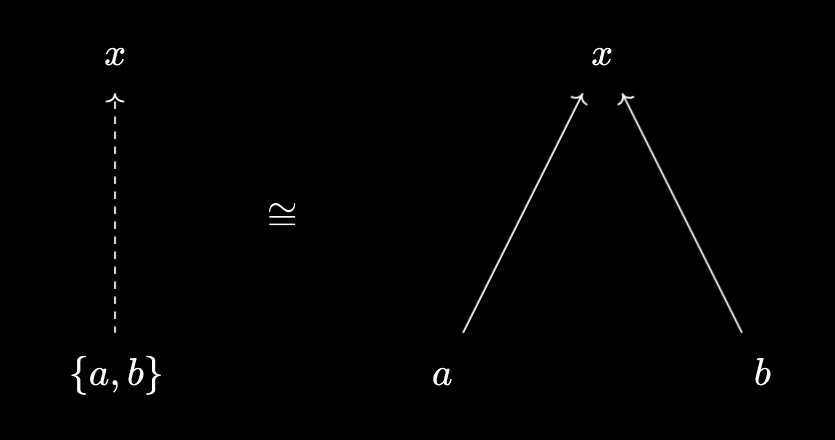

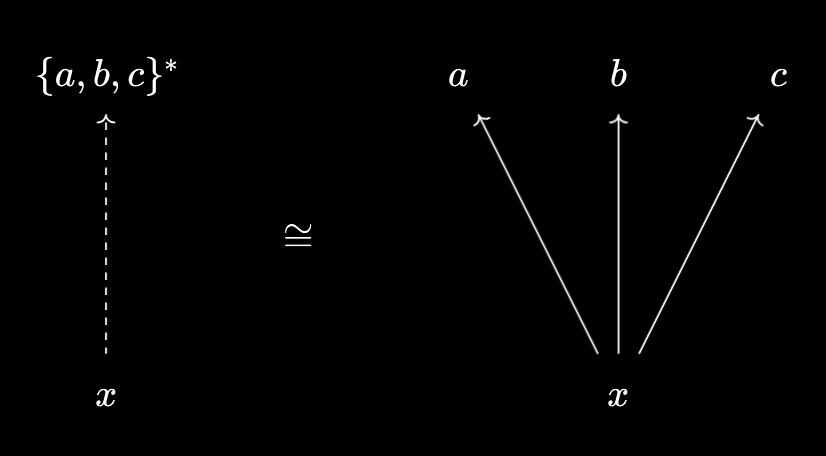

In this case, we can view the set \(\{a, b\}\) as a virtual object over/under our ordered set of numbers. Define \(x \prec \{a, b\} := x \leq a \text{ and } x \leq b\) to view it as a virtual object over our set, and \(\{a, b\} \prec x := a \leq x \text{ and } b \leq x\) to view it as a virtual object under our set:

In the language of the previous article, both of these virtual objects are representable. If we view \(\{a, b\}\) as a virtual object over our set, then it is representable by $\min(a, b)$. Indeed, we know that \(x \leq \min(a, b) \iff x \prec \{a, b\}\), which by Baby Yoneda (i.e. following the identity) implies that $\min(a, b)$ and \(\{a, b\}\) are equivalent, and thus $\min(a, b)$ represents \(\{a, b\}\). Dually, if we view \(\{a, b\}\) as a virtual object under our set, then it is representable by $\max(a, b)$.

We can generalise these observations in two directions - to arbitrary ordered sets $X$, and arbitrary subsets $S \subset X$. More precisely:

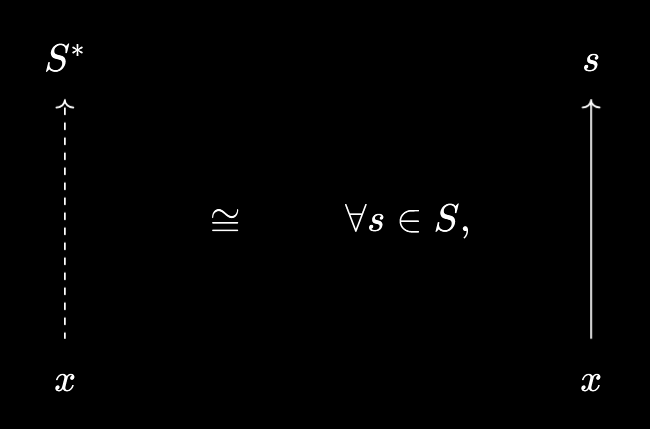

- We can view $S$ as a virtual object over $X$, \(S^*\), by defining \(x \prec S^* := \forall s \in S, x \leq s\).

- We can view $S$ as a virtual object under $X$, \(S_*\), by defining \(S_* \prec x := \forall s \in S, s \leq x\).

If \(S^*\) is representable, we call the representation the meet of all elements in $S$, denoted by $\bigwedge_{s \in S} s$. If \(S_*\) is representable, we call the representation the join of all elements in $S$, denoted by $\bigvee_{s \in S} s$. For example, $\min(a, b) = a \wedge b$, and $\max(a, b) = a \vee b$. For $P(A)$ viewed as a preorder (the powerset of $A$), we have $S \cap T = S \wedge T$, and $S \cup T = S \vee T$ for subsets $S, T \subset A$, which helps explain the “meet” and “join” terminology. Note that, by the results in the previous article, the meet and join are unique up to equivalence (and thus, in a partial order, strictly unique).

In the rest of today’s article, we’ll explore the concept of meets and joins in more detail - how they interact with each other, how they interact with virtual objects, and how they can be used to compute representations when they exist!

Empty Meets and Joins

The simplest possible case to consider is when $S = \emptyset$. In this case, the virtual object \(\emptyset^*\) is defined by \(x \prec \emptyset^* := \forall s \in \emptyset, x \leq s\). But the right-hand side is always true, vacuously. Hence, \(\forall x \in X, x \prec \emptyset^*\). Similarly, we have that \(\forall x \in X, \emptyset_* \prec x\).

What would it mean for these virtual objects to be representable? Well, if \(\emptyset^*\) is representable by some $t \in X$, then we must necessarily have $\forall x \in X, x \leq t$. This definition may look familiar - it’s precisely what it means for $t$ to be the greatest element of $X$. For example, if $X = P(A)$ for some set $A$, ordered by set inclusion, then \(\emptyset^*\) is representable by $A$ itself, since, for every subset $S \in P(A)$, we necessarily have $S \subset A$.

Similarly, if \(\emptyset_*\) is representable by some $b \in X$, then we must necessarily have $\forall x \in X, b \leq x$. This is what it means for $b$ to be the least element of $X$. For the preceding example, the empty set (regarded as a subset of $A$) is the least element of $P(A)$. Since, for every subset $S \in P(A)$, we necessarily have $\emptyset \subset A$.

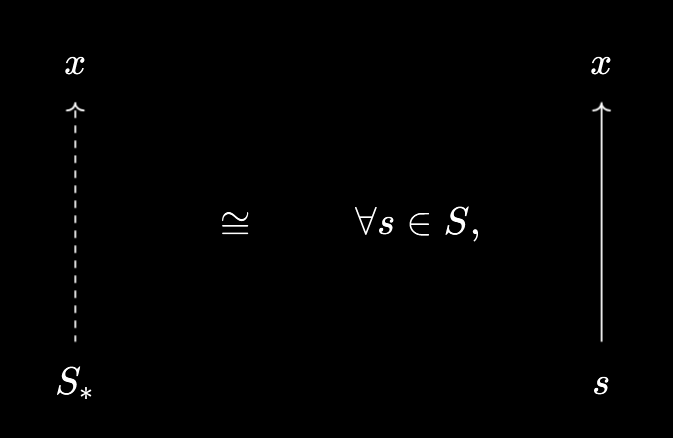

This also relates to how representations of virtual objects may be regarded as universal relationships. Recall that a representation for a virtual object $v$ over $X$ may be regarded as an element $x \in X$ together with the statement $x \prec v$, such that for any $y \in X$ satisfying $y \prec v$ we necessarily have $y \leq x$:

In this case, we may regard the relationship $x \prec v$ as the greatest relationship from an element of $X$ to $v$. For any other such relationship $y \prec v$, we have that $y \leq x$, after all. Similarly, a representation for a virtual object $w$ under $X$ may be viewed as the least relationship from $w$ to an element of $X$.

Finite Meets and Joins

We’ve already met the notion of binary meets and joins, which represent the virtual objects \(\{a, b\}^*\) and \(\{a, b\}_*\) respectively. In the universal relationship point of view, a meet of $a, b$ is an object $a \wedge b$ satisfying $a \wedge b \leq a \text{ and } a \wedge b \leq b$; and moreover, whenever $x \leq a \text{ and } x \leq b$, we necessarily have $x \leq a \wedge b$. Thus, $a \wedge b$ has a “greatest” relationship to the virtual object \(\{a, b\}^*\).

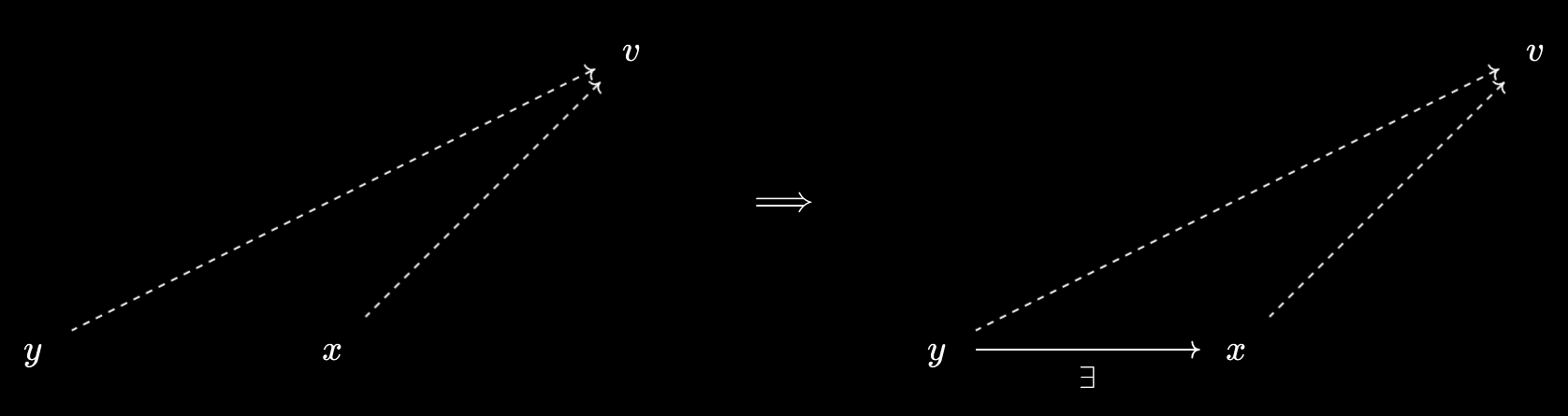

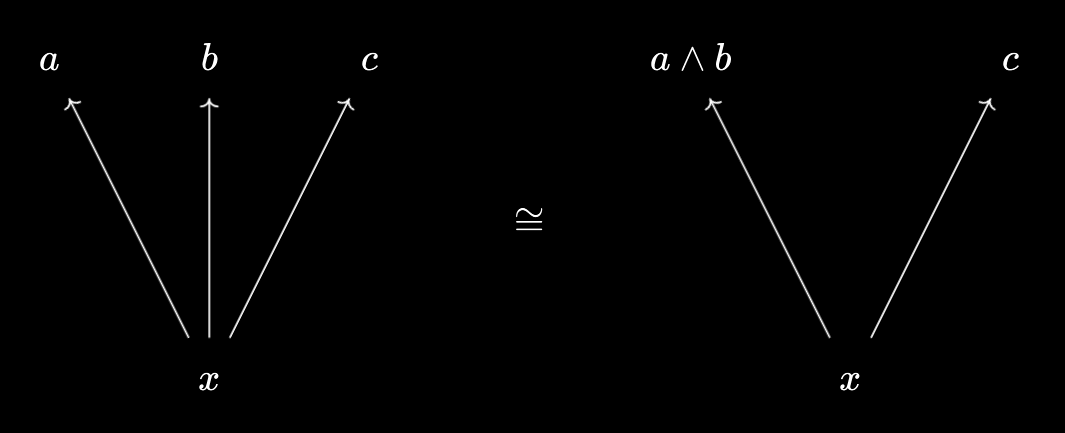

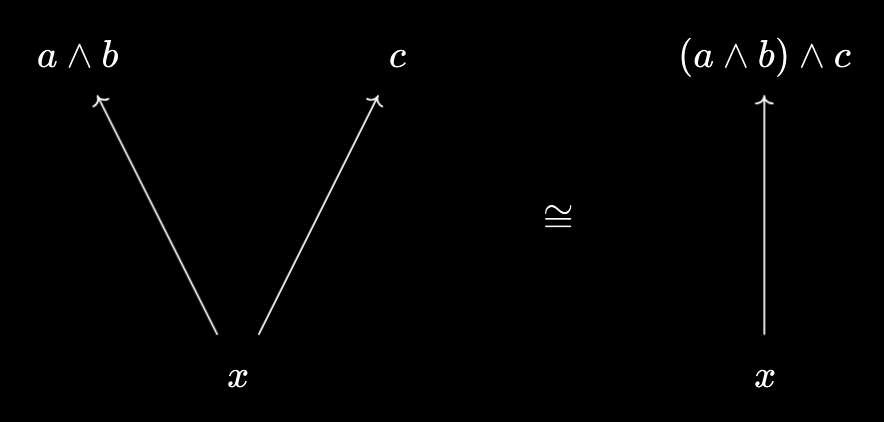

It turns out that the existence of binary meets and joins implies the existence of all finite (nonempty) meets and joins! It’s a similar strategy to how we computed the greatest common divisor of 3 numbers back in Products, Categorically, finding $\text{gcd}(a, b, c) = \text{gcd}(\text{gcd}(a, b), c)$. Let’s see how this works in general, for representing the virtual object \(\{a, b, c\}^*\):

- The virtual object \(\{a, b, c\}^*\) is defined by \(x \prec \{a, b, c\}^* := x \leq a \text{ and } x \leq b \text{ and } x \leq c\).

- Assuming we have binary meets, we can package $x \leq a \text{ and } x \leq b$ into $x \leq a \wedge b$. Thus we obtain the following equivalence:

- Then, we can further package $x \leq a \wedge b \text{ and } x \leq c$ into $x \leq (a \wedge b) \wedge c$. This gives the following equivalence:

- Thus, we’ve demonstrated that \(x \prec \{a, b, c\}^* \iff x \leq (a \wedge b) \wedge c\). Applying Baby Yoneda, we deduce that \(\{a, b, c\}^*\) and $(a \wedge b) \wedge c$ are equivalent objects, meaning $(a \wedge b) \wedge c$ is a representation of \(\{a, b, c\}^*\), as required.

A very similar argument shows that we can represent a virtual object \(F^*\) corresponding to a (nonempty) finite subset $F$ by repeatedly taking binary meets, and dually represent \(F_*\) by repeatedly taking binary joins. Thus, binary meets/joins suffices to guarantee the existence of (nonempty) finite meets and joins!

Arbitrary Meets and Joins

Iterated Meets

For arbitrary meets and joins, we can use a similar technique as the previous section to help compute larger meets/joins in terms of iterated smaller ones. Namely, we have the following result:

Let $S \subset X$, and \((S_i)_{i \in I}\) be a family of subsets with \(\bigcup_{i \in I} S_i = S\). Suppose each $S_i$ has a meet $m_i$, and moreover the collection \((m_i)_{i \in I}\) has a meet $m$. Then $m$ is a meet of $S$.

The proof is analogous to the result that finite meets may be computed from binary meets:

- By definition, $x \leq m \iff \forall i \in I, x \leq m_i$

- Using the definition of $m_i$, that’s $\iff \forall i \in I, \forall s \in S_i, x \leq s$

- And since \(\bigcup_{i \in I} S_i = S\), that’s $\iff \forall s \in S, x \leq s$.

- Thus, $x \leq m$ is equivalent to \(x \prec S^*\), meaning $m$ represents \(S^*\). So $m$ is a meet of $S$!

Cofinality

Besides partitioning, there are other helpful ways to compute meets and joins. As a silly example, if $S$ has a least element $b$, then $b$ works as a meet of $S$ - conversely, if $S$ has a greatest element $t$, then $t$ works as a join of $S$. This is because $x \leq b \implies \forall s \in S, x \leq s$ by transitivity, and $[\forall s \in S, x \leq s] \implies x \leq b$ since in particular $b \in S$.

We can generalise this observation to help compute meets and joins of large subsets by computing meets/joins of specially-chosen smaller subsets:

A subset $T \subset S$ is called cofinal if $\forall s \in S, \exists t \in T, s \leq t$. It is called coinitial if $\forall s \in S, \exists t \in T, t \leq s$.

Note that a singleton subset \(\{t\}\) is cofinal if and only if $t$ is a greatest element of $S$, and a singleton subset \(\{b\}\) is coinitial if and only if $b$ is a least element of $S$. As another example, under the usual ordering, a subset of $\mathbb{N}$ is cofinal if and only if it is infinite, while it is coinitial if and only if it contains $0$.

Then, here’s the key result:

If $T \subset S$ is cofinal, then $T$ has a join if and only if $S$ has a join. If either of these are satisfied, then the join of $T$ equals the join of $S$. Dually, if $T \subset S$ is coinitial, then $T$ has a meet if and only if $S$ has a meet. If either of these are satisfied, then the meet of $T$ equals the meet of $S$.

The strategy for proving this is to show the corresponding virtual objects are equivalent. We’ll demonstrate this for \(T_*\) and \(S_*\) for $T \subset S$ cofinal - the other case follows analogously:

- Suppose $\forall s \in S, s \leq x$. Then since $T \subset S$, we know that $\forall t \in T, t \leq x$, since this is a weaker condition.

- Conversely, suppose that $\forall t \in T, t \leq x$. We need to show that, given an arbitrary $s \in S$, we must have $s \leq x$.

- By cofinality, there exists some $t \in T$ for this $s$ such that $s \leq t$.

- And since we know that $\forall t \in T, t \leq x$, we can use transitivity to conclude $s \leq x$, as required.

So \(T_*\) and \(S_*\) are equivalent virtual objects! Thus, one is representable if and only if the other is, and they have the same representations.

Interactions between Meets and Joins

We know that “iterated” meets produce larger meets, and iterated joins produce larger joins. How about the interactions of meets with joins? The main result we’ll prove along these lines is the following:

Let $f : A \times B \to X$ be a function into an ordered set $X$. Then \(\bigvee_{a \in A} \bigwedge_{b \in B} f(a, b) \leq \bigwedge_{b \in B} \bigvee_{a \in A} f(a, b)\).

As an example, we have that for real-valued functions, $\sup_a \inf_b f(a, b) \leq \inf_b \sup_a f(a, b)$.

To prove this, we’ll rely on the corresponding universal properties for meets and joins:

- \(\bigvee_{a \in A} \bigwedge_{b \in B} f(a, b) \leq \bigwedge_{b' \in B} \bigvee_{a' \in A} f(a', b')\) if and only if \(\forall a \in A, \bigwedge_{b \in B} f(a, b) \leq \bigwedge_{b' \in B} \bigvee_{a' \in A} f(a', b')\), using the universal property for joins.

- Then, that’s if and only if \(\forall a \in A, \forall b' \in B, \bigwedge_{b \in B} f(a, b) \leq \bigvee_{a' \in A} f(a', b')\).

- For this, we appeal to the “univeral relationship” form. Namely, \(\forall a \in A, \forall b' \in B, \bigwedge_{b \in B} f(a, b) \leq f(a, b')\). And \(f(a, b') \leq \bigvee_{a' \in A} f(a', b')\). Thus, we can establish the previous relationship by transitivity!

One intuition I like to use for this is that meets correspond to “products” while joins correspond to “sums”. Then the inequality says that a sum of products is less than or equal to the corresponding product of sums - which, if you imagine expanding out the product of sums using a distributive law, seems sensible.

Relation to Representability

Respecting Meets and Joins

Meets and joins are simple examples of representable virtual objects. However, it turns out that they can be used to both check whether a virtual object might be representable, as well as compute the associated representation if it exists. In this section, we’ll see how!

The first important result is that, if a virtual object $w$ under $X$ is representable, it must respect meets:

Suppose $w$ is a virtual object under $X$ that is representable. Then \([w \prec \bigwedge_{s \in S} s] \iff \forall s \in S, w \prec s\).

Note that if $w$ was an actual object, this is just the definition of what meets are supposed to be. But, while $w$ may not be an actual object, being representable means it is equivalent to one - thus, we can transport the relationships along the equivalence to deduce the property above.

Similarly, if a virtual object $v$ over $X$ is representable, it must respect joins:

Suppose $v$ is a virtual object over $X$ that is representable. Then \([\bigvee_{s \in S} s \prec v] \iff \forall s \in S, s \prec v\).

So, respecting meets/joins is a necessary condition for a virtual object under/over $X$ to be representable. But it turns out that, if $X$ has enough meets/joins, this is in fact sufficient!

Computing Representations

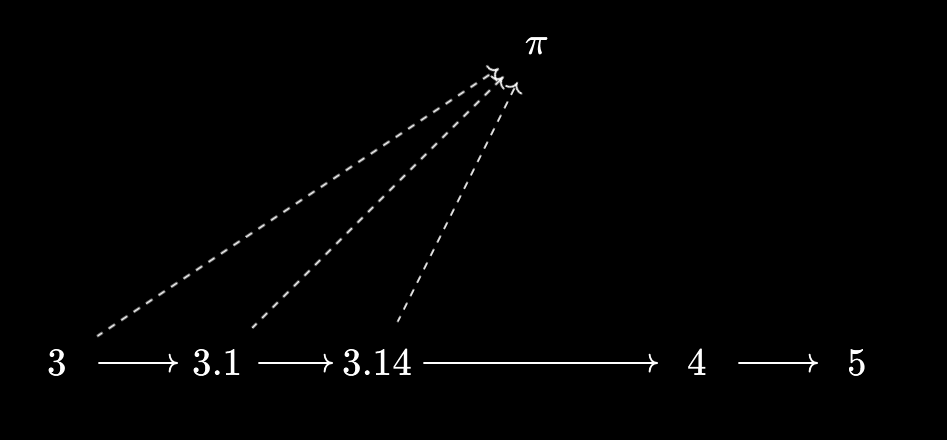

To see why, it helps to recall the example of real numbers as dedekind cuts from The Baby Yoneda Lemma:

Part of the point of dedekind cuts is to help “complete” the rationals by adding in suprema, which we now know are joins. When we extend to real numbers, $\pi$ is then equal to the supremum of all real numbers below it.

The notation suggests a strategy to compute a representation for a virtual object $v$ over an ordered set $X$ that has joins - namely, we take the join of all $x \in X$ “below” $v$! More precisely, a candidate representation is \(\bigvee_{x \in X, x \prec v} x\).

Does this work? Let’s try to check whether this really is equivalent to $v$:

- Let \(S = \{x \in X \mid x \prec v\}\). We want to show $v$ is equivalent to $S$, and we’ll break this up into two sections.

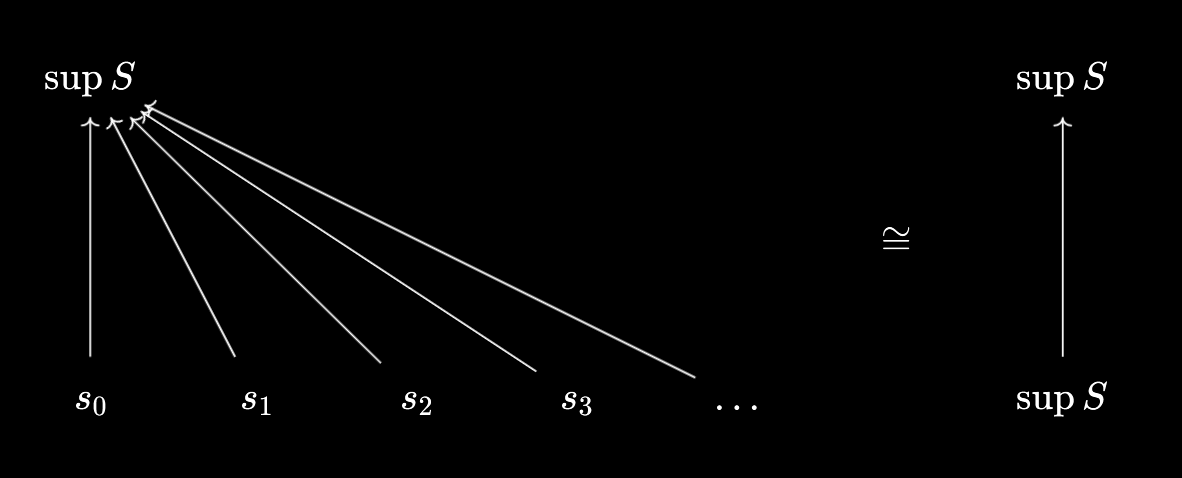

- First, let’s show \(v \prec \bigvee_{s \in S} s\). By definition, that means \(\forall y \in X, y \prec v \implies y \leq \bigvee_{s \in S} s\).

- Well, suppose $y \prec v$. That implies $y \in S$.

- But that necessarily implies \(y \leq \bigvee_{s \in S} s\), by the “universal relationship” form of joins! This is a bit easier to see if we denote \(\bigvee_{s \in S} s\) by $\sup S$:

- Explicitly, \(\bigvee_{s \in S} s\) must be an upper bound of $S$, so \(y \in S \implies y \leq \bigvee_{s \in S} s\).

- Conversely, let’s show \((\bigvee_{s \in S} s) \prec v\). Because $v$ respects joins, this is equivalent to showing $\forall s \in S, s \prec v$

- But the definition of $S$ is precisely the subset of elements of $X$ that are below $v$! So this is true.

Hence, we have the following result:

Suppose $v$ is a virtual object over $X$ that respects joins, and that the join \(\bigvee_{x \in X, x \prec v} x\) exists. Then this object represents $v$. Dually, if $w$ is a virtual object under $X$ that respects meets, and the meet \(\bigwedge_{x \in X, w \prec x} x\) exists, then this represents $w$.

This explains results like “the subgroup generated by a subset is the intersection of all subgroups containing that subset”:

- More precisely, if $S \subset G$ is a subset, for $G$ a group, we may view it as a virtual object under the collection of subgroups of $G$, defining $S \prec H := S \subset H$ for $H \leq G$ a subgroup.

- Note that meets in the collection of subgroups are just intersections, since the intersection of two subgroups is a subgroup.

- So $S \prec H \wedge K \iff S \subset H \cap K \iff S \subset H \text{ and } S \subset K \iff S \prec H \text{ and } S \prec K$. This means $S$ respects (binary) meets! The case of arbitrary meets follows analogously.

- Thus, we may compute the representation of $S$ as \(\bigwedge_{H \leq G, H \supset S} H\), i.e. the intersection of all subgroups containing $S$.

Dually, this also explains results like the interior of a subset $S$ of a topological space being the union (join) of all open sets $U$ with $U \subset S$. We’re simply using joins to compute the representation of $S$ as a virtual object!

Another important application of this result is the ability to compute joins in terms of meets, and vice-versa. Namely, we have the following result:

Suppose $X$ is an ordered set that has all meets. Then it also has all joins.

Here’s the idea:

- We take a subset $S \subset X$, and consider the virtual object \(S_*\) under $X$, defined by \(S_* \prec x := \forall s \in S, s \leq x\).

- Note that \(S_*\) respects meets! Namely, if we have $T \subset X$, then \(S_* \prec \bigwedge_{t \in T} t := \forall s \in S, s \leq \bigwedge_{t \in T} t \iff \forall s \in S, \forall t \in T, s \leq t\). Which is \(\iff \forall t \in T, S_* \prec t\), as required.

- Thus, we can compute the representation of \(S_*\) by taking the meet of all elements above it! In other words, \(\bigvee_{s \in S} s\) is \(\bigwedge_{x \in X, S_* \prec x} x\).

This allows us to define, for example, the “join” of two subgroups $H, K$ of a group $G$, even though the set-theoretic join $H \cup K$ is almost never a subgroup. We simply take the intersection of all subgroups $L \leq G$ such that $H \subset L, K \subset L$. This turns out to just be the subgroup generated by $H$ and $K$!

Why are these called “Limits”?

In more general category theory, meets and joins generalise to limits and colimits respectively. The terminology evokes the notion of limit from real analysis - for example, if we have a sequence $(a_n)$, then it converges to a limit $L$ if and only if \(\forall \epsilon > 0, \exists N \in \mathbb{N}, \forall n \geq N, \mid a_n - L \mid < \epsilon\).

As a student of category theory myself, I always wondered where the connection between these two notions of “limit” came from. Was it possible to realise analysis limits as categorical limits in some souped-up category, for example? After much careful thought, the conclusion I’ve come to is the following:

Limits in category theory and limits in analysis are instances of a common, underlying concept. The role of a limit is to summarise/compress/package the behaviour of an entire collection into a single object.

We’ve already seen the categorical side of this in Products, Categorically, where we can phrase categorical products as “packaging” a collection of objects into a single object, allowing any relationships to come along for the ride. The goal of this section is to demonstrate how this works for analytical limits.

To start with, it’ll help significantly to borrow some terminology from A Precise Notion of Approximation. Recall that we may define eventual truth as follows:

A predicate $p$ on $\mathbb{N}$ is said to be eventually true, or hold eventually, if $\exists N \in \mathbb{N}, \forall n \geq N, p(n)$.

As an exercise, you can show that $p$ is eventually true if and only if $p$ is true for all but finitely many natural numbers. We can then rephrase the limit definition as follows:

\(\forall \epsilon > 0, L - \epsilon < a_n < L + \epsilon \text{ eventually }\).

This gives us a hint towards determining the “universal property” associated with a limit. Suppose we take some arbitrary real $K$, not necessarily equal to $L$, and consider the proposition \(\forall \epsilon > 0, a_n < K + \epsilon \text{ eventually }\). By standard limit laws, this implies that \(\forall \epsilon > 0, L \leq K + \epsilon\), which actually implies \(L \leq K\).

This is promising because the final relationship is exactly what we’d need to consider viewing $L$ as a virtual object under $\mathbb{R}$. We’ve shown the implication \([\forall \epsilon > 0, a_n < K + \epsilon \text{ eventually }] \implies L \leq K\). It turns out that, for convergent sequences, the converse holds too! So we have the equivalence:

\(L \leq K \iff [\forall \epsilon > 0, a_n < K + \epsilon \text{ eventually }]\).

For the forward direction, we know that $\forall \epsilon > 0, a_n < L + \epsilon \text{ eventually }$, so we can use transitivity together with $L \leq K$ to conclude the right-hand side.

How about if $(a_n)$ is not convergent? The right-hand side still defines a virtual object under $\mathbb{R}$, and it turns out to be representable so long as $(a_n)$ is bounded from above. In fact, this is precisely what the limit supremum of $(a_n)$ does:

$\limsup_{n \to \infty} a_n \leq K \iff [\forall \epsilon > 0, a_n < K + \epsilon \text{ eventually }]$

In other words, the limit supremum of $(a_n)$ is an eventual upper bound of $(a_n)$, up to an $\epsilon$ of room (borrowing a phrase from Terence Tao). A similar universal property holds for the limit infimum:

$K \leq \liminf_{n \to \infty} a_n \iff [\forall \epsilon > 0, K - \epsilon < a_n \text{ eventually }]$

This tells us what the limit of a convergent sequence does, how it relates to other real numbers. It summarises/compresses/packages the eventual behaviour of the sequence into a single number, up to an $\epsilon$ of room! In this way, it’s not so different from a categorical limit.

Closing Thoughts

One of my longest articles to date! But I think it’s important to discuss joins and meets seriously, as this article has hopefully demonstrated.

I’ve got 2 more planned for this “Baby Yoneda” series. The next one is going to be on adjunctions, another powerful concept within category theory. And, much like the link between analytical and categorical limits, I will aim to explain the link between the categorical notion of “adjoint functor” with the notion of “adjoint linear map” from linear algebra!