Products, Categorically

Packaging Objects

The modern foundations of mathematics are set theory, most commonly ZFC. This introduces the concept of a set as a primitive notion, informally a collection of (mathematical) things. Much like the 1s and 0s of binary, it’s possible to encode all other mathematical structures purely in terms of souped-up sets.

Philosophically, this suggests the notion of bundling together disparate objects into a single place is fundamental to the practice of mathematics. Indeed, this aligns well with Henri Poincaré’s adage: “Mathematics is the art of giving the same name to different things.” We don’t think of elements of a set as equal per se; instead, giving a single name to the entire collection allows us to manipulate it as a unit, and build further concepts on top. In short - sets are really useful!

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that this concept of “packaging together objects” plays a major role within Category Theory. This is the subject of today’s article - a way to view categorical products as packagers. The key insight will turn out to be that it isn’t sufficient to only package objects together; instead, following the spirit of category theory, we must also ensure that we can package morphisms.

Packaging Inequalities

Let’s start with an elementary example - minima and maxima! Given two numbers, say $3$ and $5$, their minimum is defined to be the smaller of the two, while the maximum is defined to be the larger of the two. Thus, $\min(3, 5) = 3$ while $\max(3, 5) = 5$.

Of course, if you know the actual values, it’s (hopefully) obvious what the min and max are! Thus, they tend to be more useful as operations you can do on variables, i.e. as functions. Anyone who’s had some experience with real analysis proofs will be familiar with needing to take $\min(\delta_1, \delta_2)$ or $\max(N_1, N_2)$, for example.

That tells us what $\min$ and $\max$ “are”. However, their universal property focuses on what they do - how they interact with and relate to other numbers, and what you can use them for. Notice that the following holds:

Let $a,b, x$ be numbers. If $x \leq \min(a, b)$ then certainly $x \leq a$ and $x \leq b$. But the converse is true - if $x \leq a$ and $x \leq b$, then $x \leq \min(a, b)$, since $\min(a, b)$ has to be one of $a$ or $b$.

In symbols, we can write this as $x \leq \min(a, b) \iff x \leq a \land x \leq b$. So this is what $\min(a, b)$ does - it lets you package inequalities together, in a reversible way! Not only do the individual numbers $a$ and $b$ get compressed into a single number $\min(a, b)$, but so do their relationships with other numbers.

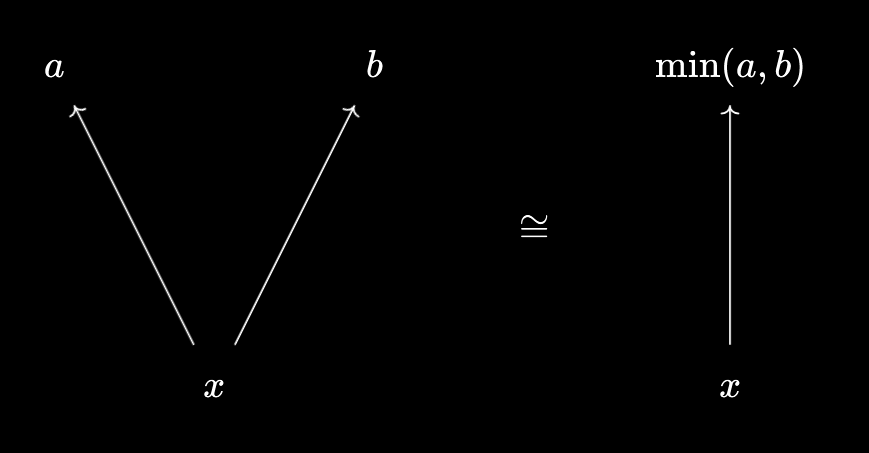

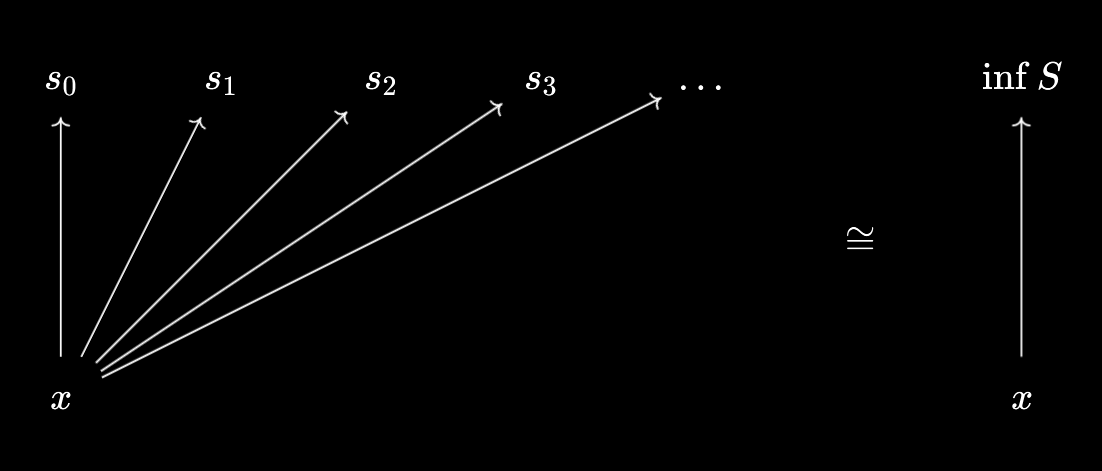

We can illustrate this diagrammatically as follows:

Here, we visualise the relationship $x \leq a$ by an arrow from $x$ to $a$. As we can see, $\min(a, b)$ allows us to package both the objects $a$ and $b$ together, as well as their relationships with other numbers! In a reversible way.

Within analysis, the reason why $\min(\delta_1, \delta_2)$ is often used is to ensure that two conditions hold simultaneously - for one condition, you need $\mid x - a \mid < \delta_1$, and for the other you need $\mid x - a\mid < \delta_2$. The observation above shows that this is no coincidence - $\min(\delta_1, \delta_2)$ is precisely the construction you need to “package” or “compress” the two conditions into a single one.

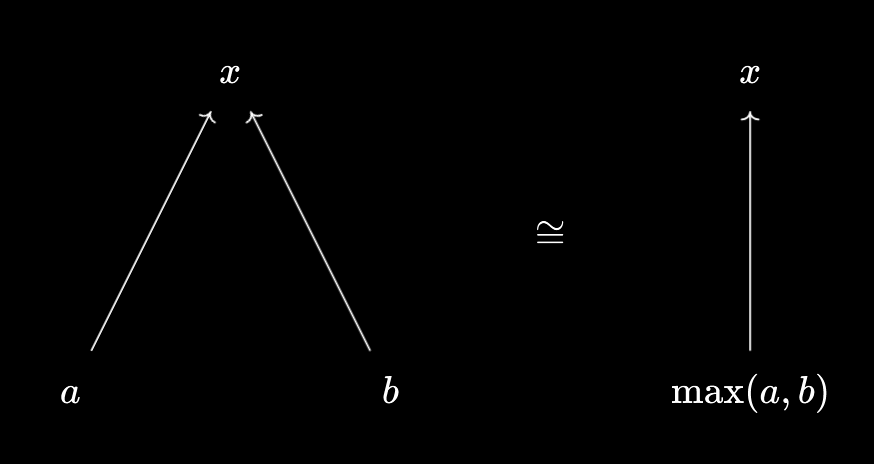

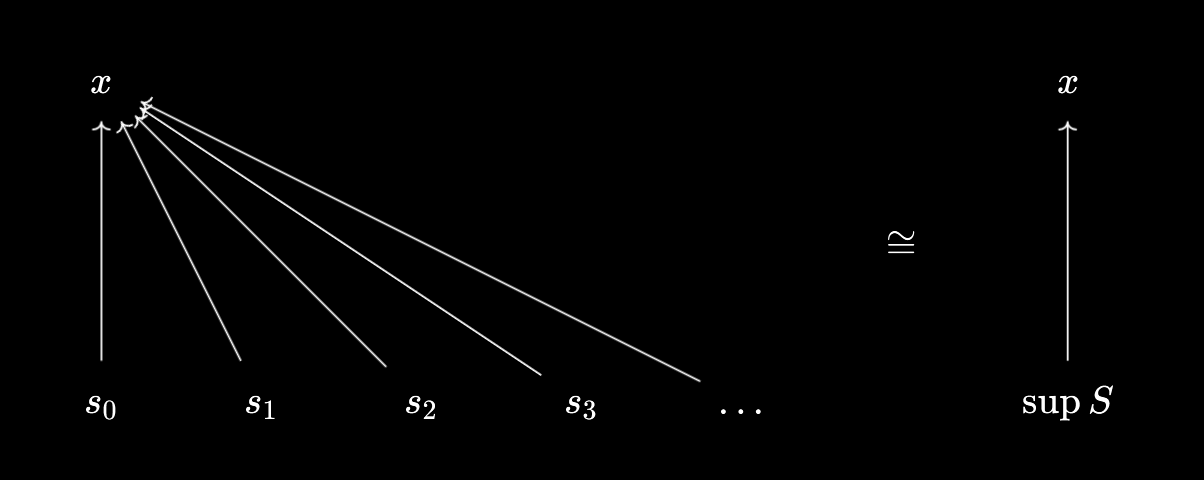

A similar property holds for maxima:

$x \geq \max(a, b) \iff x \geq a \land x \geq b$.

So, $\max(a, b)$ “does” a pretty similar thing to $\min(a, b)$ in terms of allowing you to package inequalities together. We’re just dealing with $\geq$ relations rather than $\leq$ relations. When working with sequences, you might need $n \geq N_1$ and $n \geq N_2$ simultaneously, and $\max$ is designed so that we can replace this with the equivalent condition $n \geq \max(N_1, N_2)$.

And again, we can visualise this diagrammatically as follows:

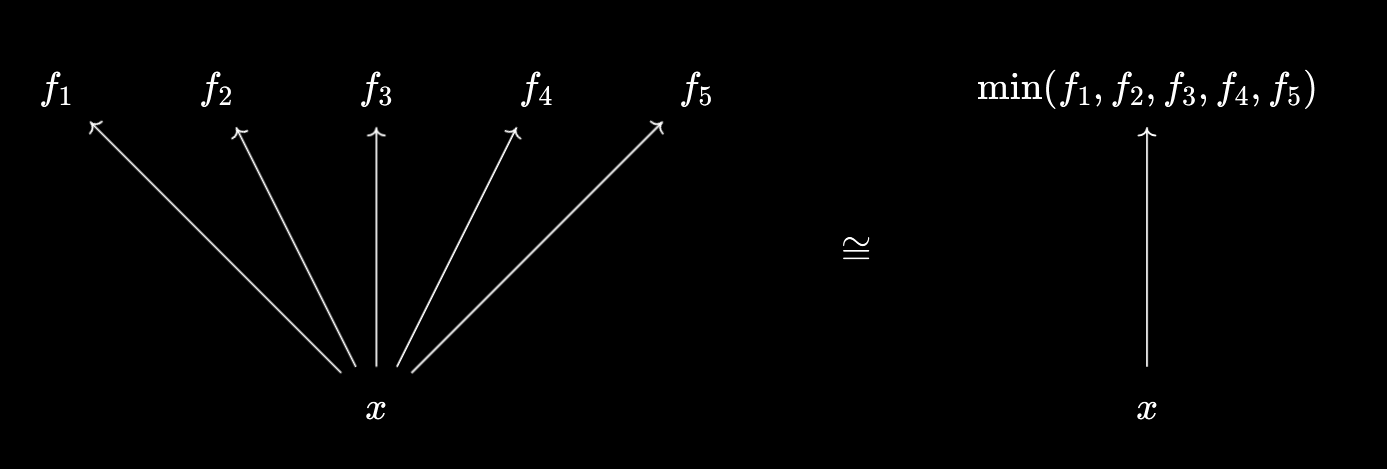

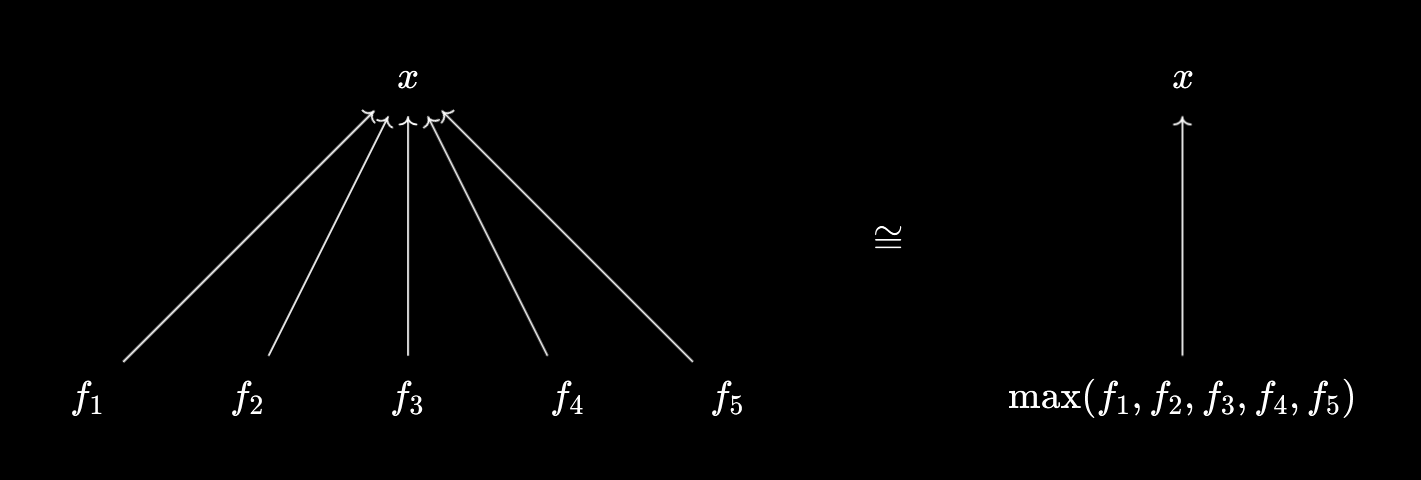

We can extend this to larger collections of numbers. For example, $x \leq \min(a, b, c) \iff x \leq a \land x \leq b \land x \leq c$, and $x \geq \max(a, b, c) \iff x \geq a \land x \geq b \land x \geq c$. In general, if $F$ is a finite set, we have:

$x \leq \min F \iff \forall f \in F, x \leq f$, and $x \geq \max F \iff \forall f \in F, x \geq f$.

So, what more general minima and maxima “do” is allow us to compress finitely many inequalities into a single one, in a reversible way:

How about if we try generalising to larger sets? This turns out to be exactly what suprema and infima are designed to do! Namely, we have the following property:

$x \leq \inf S \iff \forall s \in S, x \leq s$, and $x \geq \sup S \iff \forall s \in S, x \geq s$.

Let’s unpack the supremum property:

- If we have that, for all $s \in S$, $x \geq s$, then $x$ is an upper bound of $S$. So, since the supremum is meant to be the least upper bound, we have $x \geq \sup S$.

- Conversely, suppose $x \geq \sup S$. Since $\sup S$ is an upper bound, we have that $\forall s \in S, \sup S \geq s$. Thus, by transitivity, we can conclude $\forall s \in S, x \geq s$.

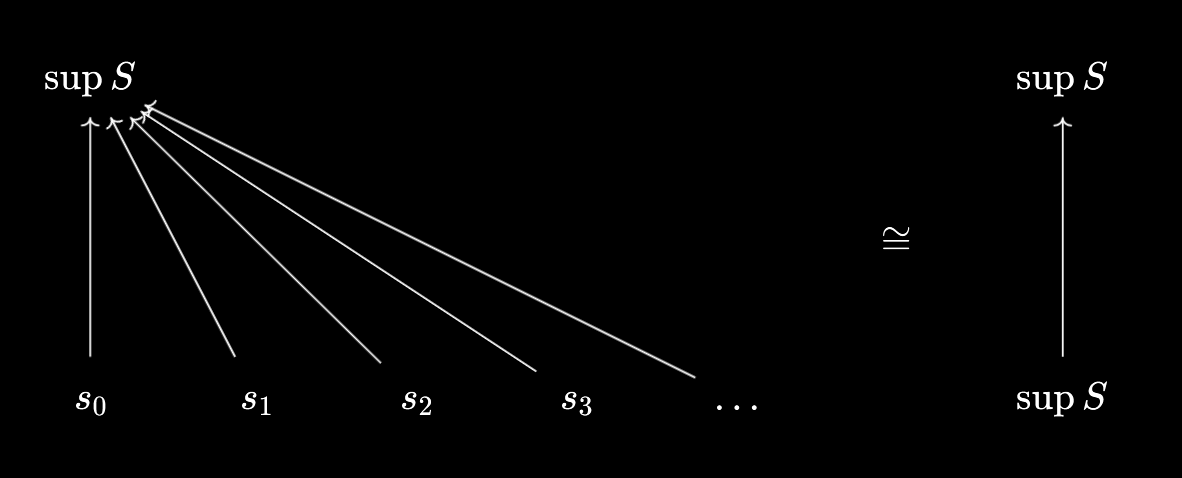

So these really are equivalent! Even though the definitions of suprema and infima are a little more involved than maxima and minima, we see that they’re all “doing” the same thing - packaging and unpackaging inequalities together:

There’s also an interesting interpretation of why $\sup S$ must be an upper bound of $S$ itself. We know that $\sup S \geq \sup S$ trivially - so, by applying the “unpackaging” property, we see that we can conclude $\forall s \in S, \sup S \geq s$.

Packaging Relationships

What other kinds of relationships might we be able to package/compress? Other than inequalities, another way in which two numbers may be related is divisibility - for example, $3$ is a factor of $30$, while $80$ is a multiple of $16$. We’ll use the notation $a \mid b$ to represent “a divides b” - formally, that there exists an integer $k \in \mathbb{Z}$ such that $b = ak$. So $3 \mid 30$ while $16 \mid 80$.

You may recall the notion of a “greatest common divisor” from school - the largest among all common divisors of two numbers. In symbols, we can write $\text{gcd}(a, b) = \max {d \in \mathbb{Z} \mid d \mid a \land d \mid b }$. This implies that $d \mid a \land d \mid b \implies d \leq \text{gcd}(a, b)$.

However, we can use a little bit of number theory to strengthen this statement. Bézout’s identity says that there exist integers $x, y \in \mathbb{Z}$ such that $\text{gcd}(a, b) = ax + by$. So if $d \mid a \land d \mid b$, then certainly $d \mid ax + by$, so $d \mid \text{gcd}(a, b)$, which is more information than simply knowing $d \leq \text{gcd}(a, b)$. In fact, this becomes an equivalence so that we have:

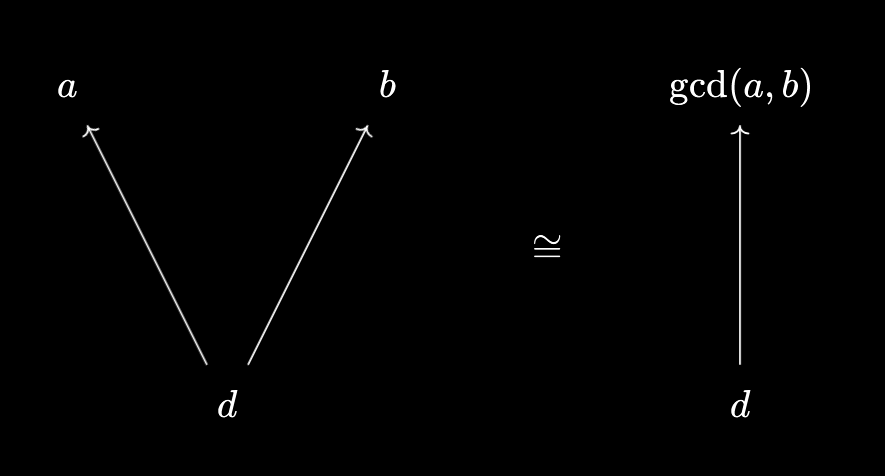

$d \mid \text{gcd}(a, b) \iff d \mid a \land d \mid b$

So, what $\text{gcd}(a, b)$ “does” is allow you to package divisibility relations! Similarly, we have the property:

$\text{lcm}(a, b) \mid m \iff a \mid m \land b \mid m$

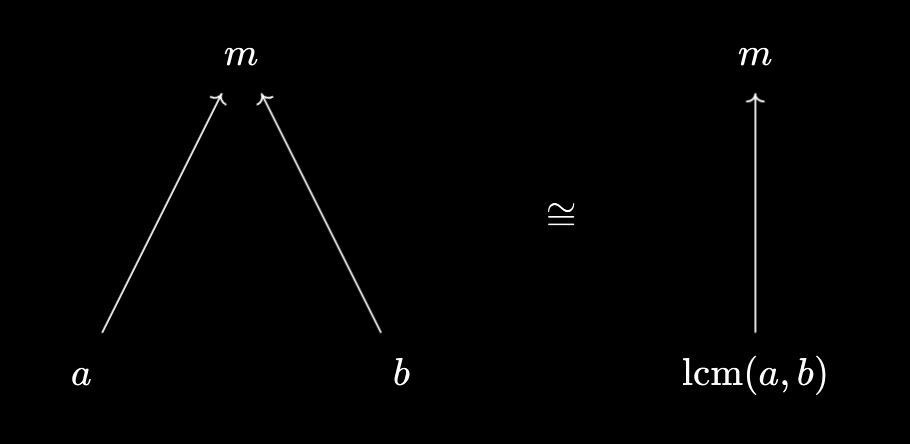

Thus, the lowest common multiple allows you to package together two divisibility relations in the other direction, in a reversible way. Again, if we represent divisibility as an arrow, we have familiar packaging diagrams:

These properties also hold for the natural generalisations of $\text{gcd}$ and $\text{lcm}$ to sets of 3 or more numbers. In my childhood, I remember coming up with a different strategy for computing $\text{gcd}(a, b, c)$ that didn’t require me to list out all common divisors of $a, b, c$. If I wanted to find $\text{gcd}(24, 15, 54)$ for example, I would first compute $\text{gcd}(24, 15) = 3$, followed by $\text{gcd}(3, 54) = 3$.

This seems to suggest the following relationship - $\text{gcd}(a, b, c) = \text{gcd}(\text{gcd}(a, b), c)$. In fact, we can use the universal property to prove this! We make the following manipulations:

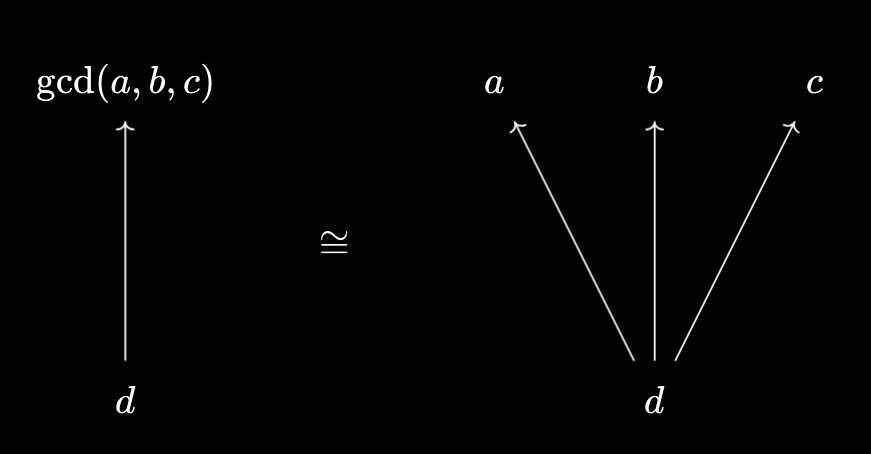

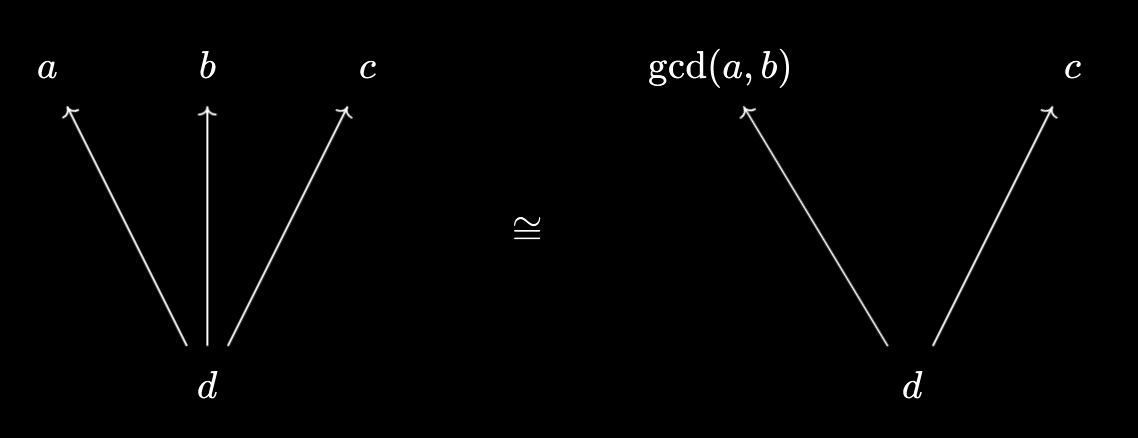

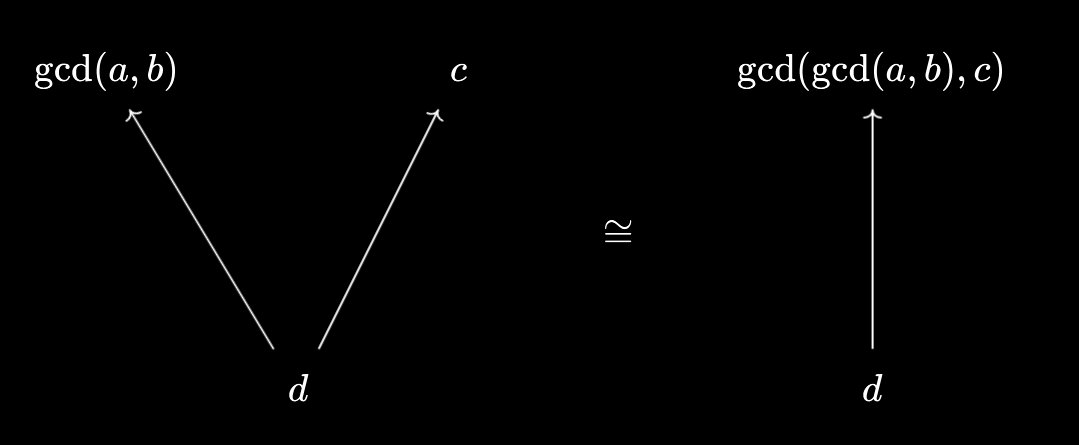

- $d \mid \text{gcd}(a, b, c) \iff d \mid a \land d \mid b \land d \mid c$

- $d \mid a \land d \mid b \land d \mid c \iff d \mid \text{gcd}(a, b) \land d \mid c$

- $d \mid \text{gcd}(a, b) \land d \mid c \iff d \mid \text{gcd}(\text{gcd}(a, b), c)$

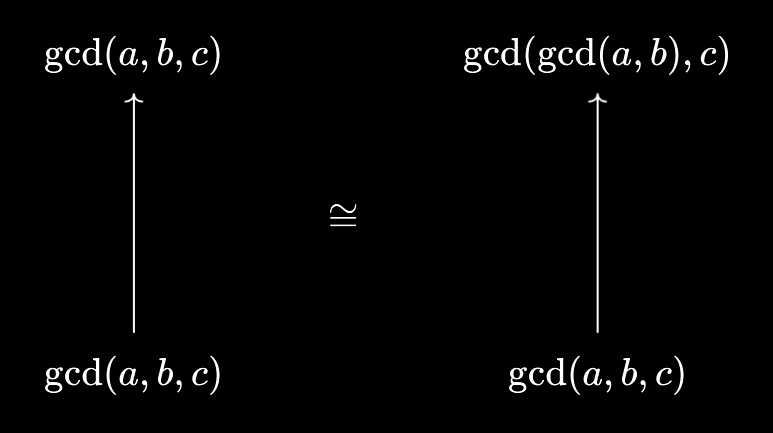

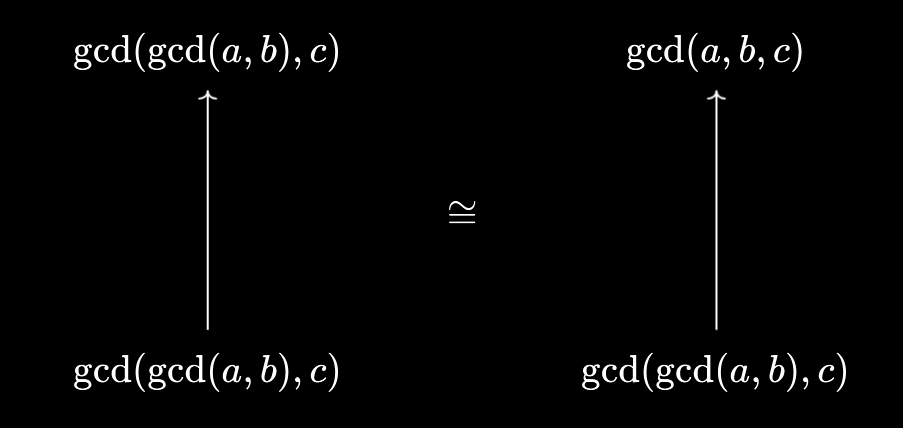

Visually, this corresponds to:

Thus, we’ve demonstrated $d \mid \text{gcd}(a, b, c) \iff d \mid \text{gcd}(\text{gcd}(a, b), c)$. But it’s generally true that if $d \mid x \iff d \mid y$, then we must necessarily have $x = y$! To see this, we can substitute $d = x$ to deduce $x \mid y$, and then substitute $d = y$ to deduce $y \mid x$, from which we deduce $x = y$. Again, we see the utility of “following the identity” through these packaging/unpackaging operations:

Essentially the same proof shows that we can find the $\text{gcd}$ and $\text{lcm}$ of any finite set by repeatedly applying the corresponding binary operation.

Further Examples

For sets, we have $A \subset B \cap C \iff A \subset B \land A \subset C$, and $X \cup Y \subset Z \iff X \subset Z \land Y \subset Z$

For sets-of-sets, we have $A \subset \bigcap \mathcal{F} \iff \forall F \in \mathcal{F}, A \subset F$. And $\bigcup \mathcal{G} \subset Z \iff \forall G \in \mathcal{G}, G \subset Z$. Similarly, for indexed families, we have $A \subset \bigcap_{i \in I} F_i \iff \forall i \in I, A \subset F_i$, and $\bigcup_{i \in I} G_i \subset Z \iff \forall i \in I, G_i \subset Z$.

So, what intersections and unions “do” is allow you to package together subset relations in a reversible way.

For propositions, we have $[p \implies (q \land r)] \iff [(p \implies q) \land (p \implies r)]$. And $[(q \lor r) \implies p] \iff [(q \implies p) \land (r \implies p)]$.

For predicates, we have $\forall x. [p(x) \implies (\forall y . q(x, y))] \iff \forall x \forall y. [p(x) \implies q(x, y)]$, and $\forall x . [(\exists y . q(x, y)) \implies p(x)] \iff \forall x \forall y. [q(x, y) \implies p(x)]$.

Thus, what AND and OR “do” is let you package logical implications in a reversible way - and this naturally generalises to universal and existential quantification.

Packaging Functions

You may be wondering why this notion of “packager” is called the categorical product - none of the examples we’ve seen so far seem like products in the usual sense, after all. For that, we’ll have to return to set theory, and consider cartesian products of sets.

Given two sets $A$ and $B$, what the cartesian product $A \times B$ “is” is the collection of ordered pairs $(a, b)$ with $a \in A, b \in B$. But as we’ve gotten used to, its universal property focuses on what it “does”, how it relates to and interacts with other sets, what we can use it for.

So, let’s take another set $Z$, and consider a function $f : Z \to A \times B$. Then at a particular $z \in Z$, we have an output value $f(z) = (g(z), h(z))$ for $g(z) \in A, h(z) \in B$. Thus, we may “unpackage” $f$ into a pair of functions $g : Z \to A$ and $h : Z \to B$.

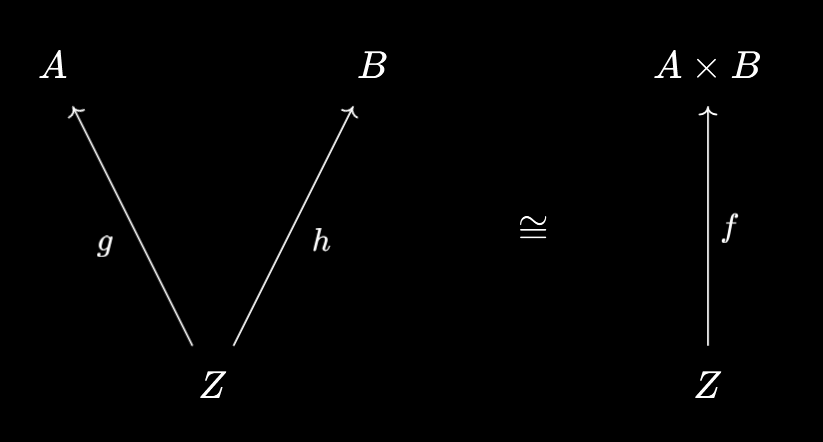

However, the converse also holds! If we have a pair of functions $g : Z \to A$ and $h : Z \to B$, then we may “package” them together into a single function $f : Z \to A \times B$ given by $f(z) := (g(z), h(z))$ for each $z \in Z$. Thus, we have the following property:

Functions $Z \to A \times B$ naturally correspond to pairs of functions $Z \to A, Z \to B$

The cartesian product is a packager! Except, instead of just packaging ordinary relationships, we’ve packaged functions together.

In fact, essentially every product you’ve met in math “does” the same thing - it lets you package and unpackage structure-preserving functions. So:

- Direct products of groups let you package and unpackage group homomorphisms.

- Direct products of vector spaces let you package and unpackage linear maps.

- Products (even infinite) of topological spaces let you package and unpackage continuous maps.

- Products of categories let you package and unpackage functors.

- Products of graphs, however you choose to define them, should be able to package and unpackage graph homomorphisms, however you choose to define those.

- Products of smooth manifolds let you package and unpackage smooth functions.

And the list goes on! The constructions vary quite a lot between different areas of math - minima and maxima, greatest common divisors, unions of sets, products of smooth manifolds. The “is” changes quite rapidly. And yet, they all seem to “do” the same thing - much like sets, categorical products let you package objects together, but in a way that also allows you to package any morphisms that come along for the ride!

The Universal Property

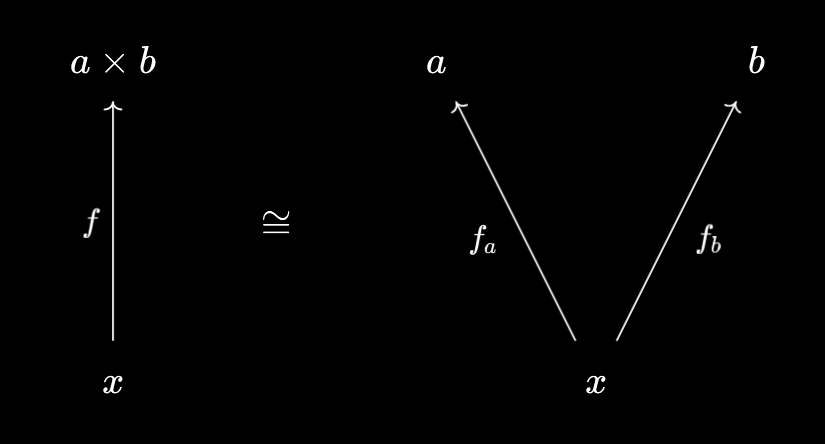

So far, we’ve seen that the categorical product can be thought of as a “packager”, that allows you to simultaneously compress objects and morphisms together. Given objects $a, b$ in a category, what the product $a \times b$ “does” is allow you to interconvert between morphisms $x \to a \times b$ and pairs of morphisms $x \to a, x \to b$:

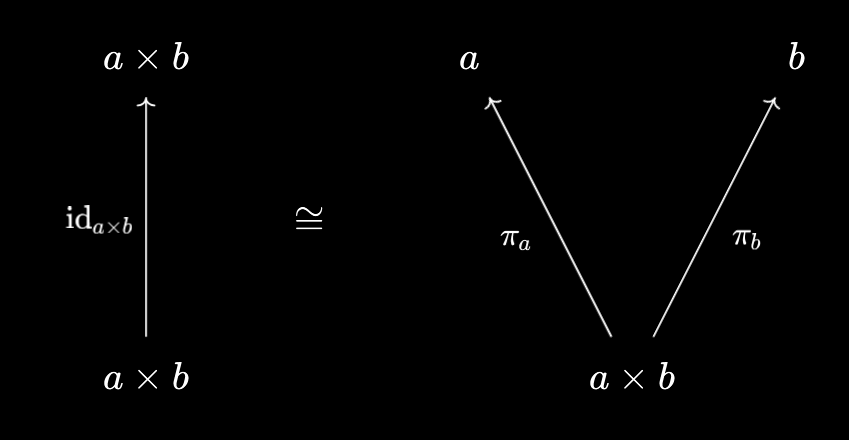

As we’ve seen in previous sections, we often get useful results from “following the identity” through these manipulations. In general, the result of unpackaging the identity \(\text{id}_{a \times b} : a \times b \to a \times b\) are the canonical/universal projections:

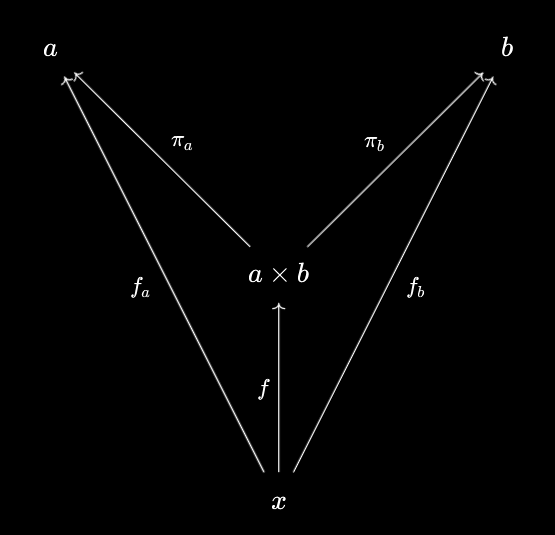

In all of the examples we’ve seen, these play a special role in the unpackaging process. The uncompressed components $f_a : x \to a$ and $f_b : x \to b$ always take the form $f_a = \pi_a \circ f, f_b = \pi_b \circ f$, which we can illustrate with the following (commutative) diagram:

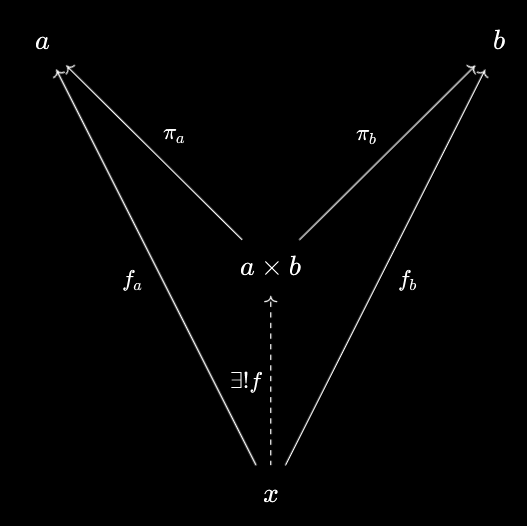

How about the packaging process? If we have a pair of morphisms $f_a : x \to a$ and $f_b : x \to b$, then we know we can package them into a single $f : x \to a \times b$. Furthermore, since packaging and unpackaging are inverses of each other, we must have that $f_a = \pi_a \circ f$ and $f_b = \pi_b \circ f$ - and moreover, $f$ is unique with that property, being the packaging of $f_a$ and $f_b$. We can illustrate this situation with this diagram:

If you’ve seen the universal property of the product before, then this diagram should be familiar! For any pair $f_a : x \to a$ and $f_b : x \to b$, there exists a unique $f : x \to a \times b$ that makes the diagram commute. So we see that the traditional form of the universal property is really just encoding the packaging nature of the categorical product, from a different perspective.

Further Reading

As an exercise, if you’ve read my post on Infinitary Cartesian Products, you might want to try proving whether this works as a packager. Is it true that functions $Z \to \prod_{i \in I} A_i$ naturally correspond to families of functions $Z \to A_i$, i.e. to elements of $\prod_{i \in I} [Z \to A_i]$?

I’ve also cheated a little bit here and used the word “natural” in this last section without formally defining it. I’m planning to release another article going through my own intuition for naturality, but personally speaking I don’t think this is essential to understand what products really are, categorically. So I’ve chosen to omit it from this article.

As always, for more details the nlab is a good place to start.