The Baby Yoneda Lemma

Following The Identity

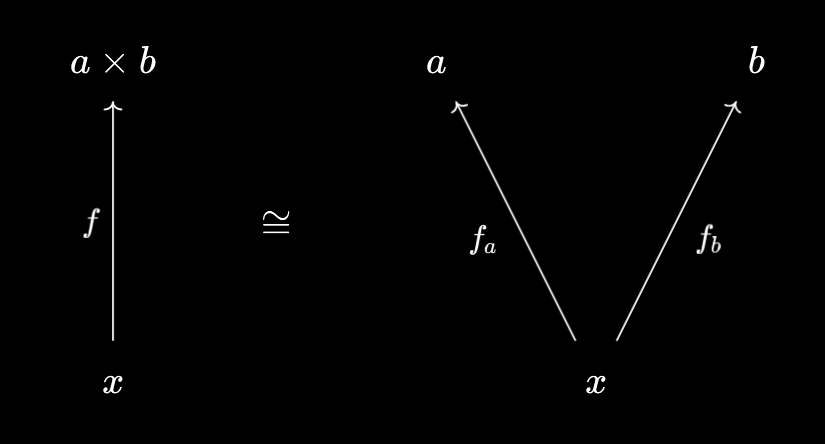

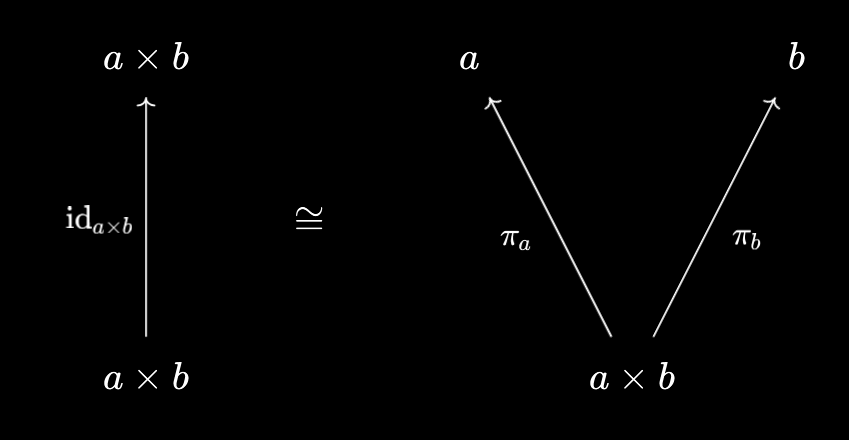

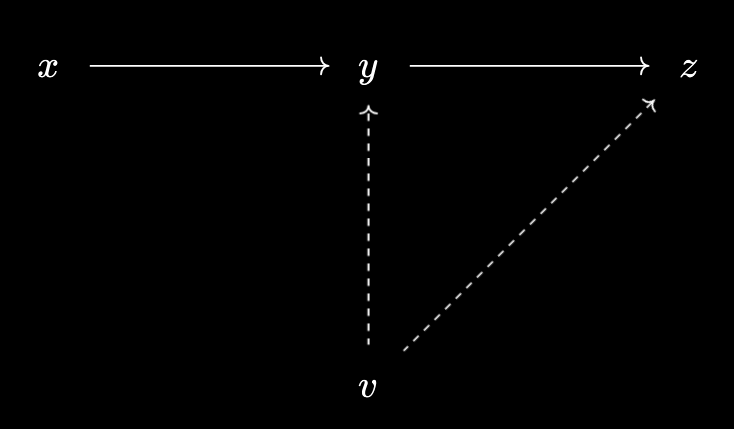

In quite a few of my recent articles, we’ve used this trick of “following the identity”. For example, we’ve seen in Products, Categorically that products can be thought of as “packagers” for morphisms:

Following the identity then gives us the universal projections, which help us unpackage general morphisms into the product:

This trick was also helpful for our “associativity of greatest common divisor” argument - in that case, we showed that $\text{gcd}(a, b, c) = \text{gcd}(\text{gcd}(a, b), c)$ indirectly, by proving $d \mid \text{gcd}(a, b, c) \iff d \mid \text{gcd}(\text{gcd}(a, b), c)$. It also made an appearance in Subset Images, Categorically, via the universal property of direct image:

$f(A) \subset B \iff A \subset f^{-1}(B)$

Taking $B = f(A)$ gives us $A \subset f^{-1}(f(A))$, so that the right-hand side can be viewed as a set-theoretic “closure” operation. Conversely, taking $A = f^{-1}(B)$ gives us $f(f^{-1}(B)) \subset B$, so that the left-hand side can be viewed as a set-theoretic “interior” operation.

As it turns out, all of these are applications of the yoneda lemma, the fundamental theorem of category theory. It has quite a reputation, from what I’ve observed; some dismiss it as a trivial result without content, some find the proof easy but the interpretation mysterious, and I’ve met lots of category theorists who say that Yoneda is crucial for the subject.

But I’m none of those - I’m a physicist! As such, I’ve got a physics-based interpretation of Yoneda that I’ve found extremely helpful in both applying and understanding it. In a sense, the style of thinking that flows from Yoneda is not that unfamiliar to a scientist, though the usual statement definitely doesn’t make this clear.

The goal of today’s article, then, is to explore a simplified version of the lemma, which I’ve affectionately titled the “Baby Yoneda Lemma”. My hope is that this will be sufficiently elementary to understand, while still capturing a lot of the “essence” of the yoneda philosophy, in a rigorous fashion. We’ll meet lots of familiar concepts along the way, like:

- Floor and ceiling of real numbers.

- Dedekind cuts.

- Interior and closure operators.

- Why is the subgroup generated by a set equal to the intersection of all subgroups containing it? Why does this trick also work for topological closure, span of a collection of vectors, topology generated by a basis?

- Orthogonal complements.

Let’s dive in!

Is-Does Duality

I’ve used the words “is” and “does” informally in some of my previous articles, and it’ll be helpful to be a bit more precise about how I’m using them.

Often, these manifest as two types of perspectives you can take on an object:

- What it “is”. The internals, how it works, what defines it, how it exists “passively”.

- What it “does”. The externals, how it interacts with other things, what it gets used for, how it exists “actively”.

For example, the “is” of a word corresponds to its definition, which dictionaries are meant to compile. These are helpful when you learn a new word from a book, say, but obviously you can’t use this when you’re first learning language! You’ll run into a circularity problem.

Instead, it can be helpful to correspond to what the word “does”, in terms of how to use it. Looking at example sentences, trying to see which words or concepts it occurs together with, figuring out the role it plays within the language. I might not be able to give a sensible definition of “chair”, but I know that I can use it to sit down!

This same phenomenon occurs quite frequently. The “is” of a machine like a train corresponds to how it works, while the “does” correspond to why you’d use it - public transportation and freight, for example. Often, money “is” just fancy paper, or disk-shaped pieces of metal, or 1s and 0s on a bank computer somewhere. But what money “does” is allow you to trade for goods and services; in that way, it gains value beyond its intrinsic, physical worth.

Physicists, too, tend to spend a lot more time in the “does” world than the “is” world. Take the electron - in some models it’s a particle, in some it’s a wave, in some it’s a wavefunction, in some it’s an excitation of a quantum field, and in condensed matter it can even cease to be a fundamental particle! What the electron “is” changes quite rapidly. However, what the electron “does” tends to stay a lot more consistent - it repels other electrons, it forms chemical bonds, it conducts electricity. Perhaps this doesn’t come as a surprise, since science is inherently empirical. Experiments only give us access to what objects “do”, and it’s up to us to tell a story of what they “are” which explains it.

Of course, this duality manifests in mathematics, too. A matrix “is” just a grid of numbers, but what it “does” is represent/induce a linear transformation. A vector “is” just an arrow in space, but what it “does” is represent a translation operation. You can view numbers on a number line “actively” as sliding transformations $x \mapsto x + k$, or perhaps scaling transformations $x \mapsto k x$. An algebraic expression like $x^3 + 4x - 2$ “is” just a sequence of letters, numbers and operators. But what it “does”, actively, is represent a function $x \mapsto x^3 + 4x - 2$. An equation like $4x + 2 = 10$ can be viewed “actively” as a function that takes in a guess for $x$, and outputs “True” or “False”, depending on whether not the guess $g$ satisfies $4g + 2 = 10$. Solving the equation amounts to finding the collection of all guesses that give an output of “True” - the rules of algebra then help find equivalent presentations of the same function, e.g. $4x = 8$, to make solving easier.

Cayley’s theorem, too, can be seen as an instance of this. One may view an element $g \in G$ of a group $G$ “actively” via its action on other elements, by sending $x \mapsto gx$. Thus, a group element induces a permutation on $G$. Note that we also have a way to go back from “does” to “is”, by following the identity element.

By this, I mean that if you’ve got a map of the form $x \mapsto gx$, but you’ve forgotten what $g$ is, you can recover it by evaluating at the identity $e$. Since you’ll have $e \mapsto g e = g$! You can recover a vector from its translation operation by following where the zero vector goes; you can recover a number from its scaling transformation by following where “1”, the mutliplicative unit, goes. In general, any identity element plays an important role in converting back from “does” to “is”, via evaluating your induced function at the identity!

Some operations can be easier in one world than another. Matrix multiplication, for example, is easier conceptually in the “does” perspective, since it becomes composition of linear maps. It thus inherits properties like associativity, or a lack of commutativity, from the corresponding properties of function composition. So it’s quite helpful to have a bridge between the two worlds, allowing you to focus on whichever is more convenient for your problem. In a strong sense, this “is-does duality” forms the essence of the Yoneda philosophy.

Orthogonal Considerations

Let’s get a little more concrete. For the remainder of this article, we’ll restrict to the way in which Yoneda manifests for ordered sets. These definitions will be relevant:

A preoder is a set $X$ together with a relation $\leq \space \subset X \times X$ that is reflexive and transitive, so $\forall x \in X, x \leq x$ and $\forall x, y, z \in X, x \leq y \text{ and } y \leq z \implies x \leq z$.

A partial order is a preorder $(X, \leq)$ that is additionally antisymmetric, meaning $x \leq y \text{ and } y \leq x \implies x = y$.

We’ve already seen quite a few examples of this structure - the natural numbers with $\leq$, the natural numbers with divisbility, subsets with inclusion. You could even take $X$ to be a set of propositions, where $p \leq q$ if and only if $p \implies q$.

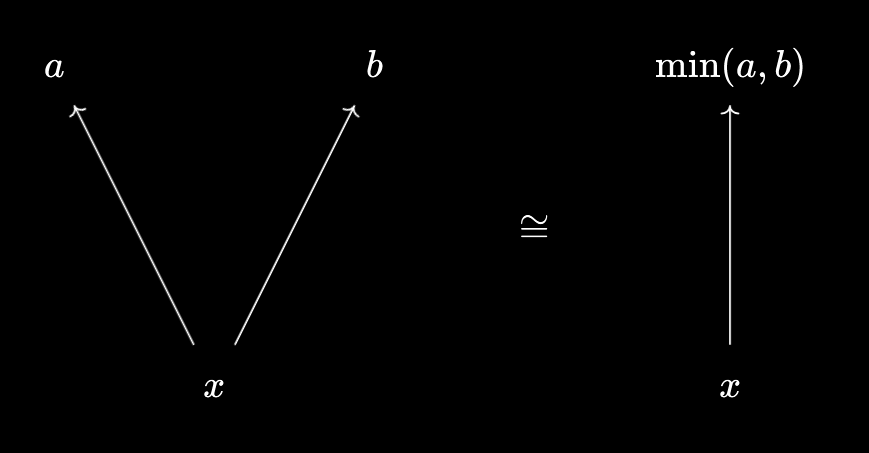

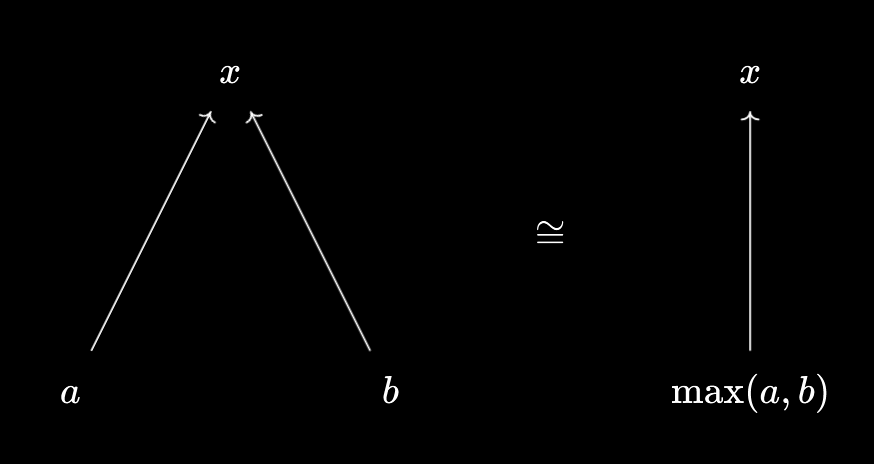

From Products, Categorically, it’s often helpful to consider what an element $x \in X$ “does”, in terms of how it relates to other elements. Namely, we get two natural comparison predicates, $p(y) = (y \leq x)$ and $q(y) = (x \leq y)$. For example, we saw the universal properties of min and max being expressed as:

$x \leq \min(a, b) \iff x \leq a \text{ and } x \leq b, \max(a, b) \leq x \iff a \leq x \text{ and } b \leq x$.

This falls into the general pattern of how is-does duality manifests in mathematics, where you consider functions induced by an object. We can also “comprehend” these predicates to get subsets, a la Indexed-Fibred Duality, \(L = \{y \in X \mid y \leq x\}\) and \(U = \{y \in X \mid x \leq y\}\). You might recognise these as the “lower” and “upper” sets corresponding to $x$.

That takes care of the points of our ordered set. What about the relationships? What does an assertion like $a \leq b$ “do”, in this perspective? Well, analogously to how the “does” of a point was a function on points, the “does” of a relationship ends up being a function on relationships.

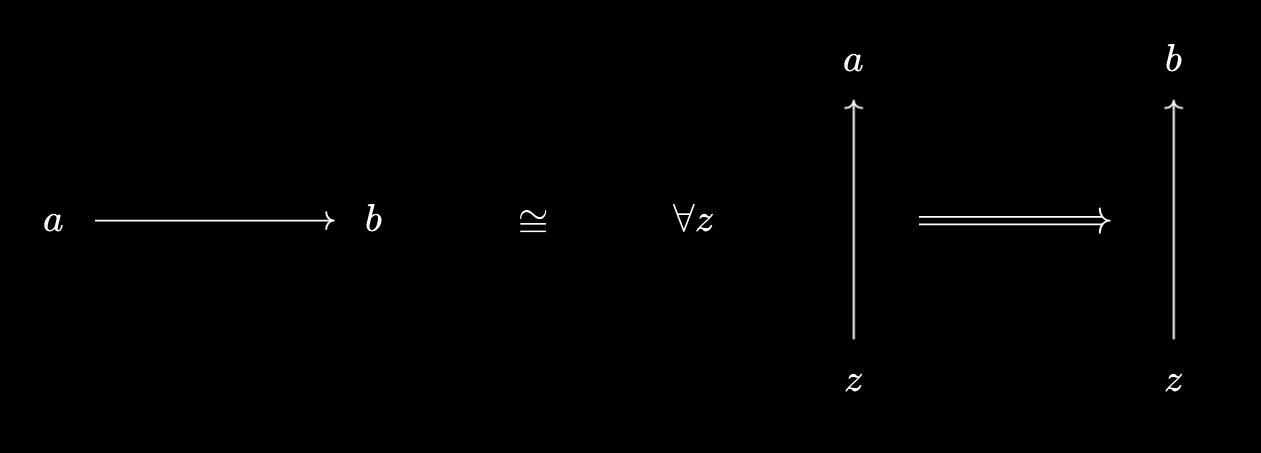

Here’s the idea. Suppose $a \leq b$. Then, for any $z \in X$, transitivity guarantees that $z \leq a \implies z \leq b$ - so, what $a \leq b$ “does” is allow you to transform the relationship $z \leq a$ into $z \leq b$. Conversely, suppose we have such a translation, i.e. we know that $\forall z \in X, z \leq a \implies z \leq b$. Then substituting $z = a$, we obtain $a \leq a \implies a \leq b$. But reflexivity guarantees $a \leq a$, so by “following the identity” we obtain $a \leq b$!

There’s also a nice way to interpret this in terms of “orthogonal complements”. In linear algebra, we say that subspaces $U, W$ of a vector space $V$ are orthogonal complements if and only if the following is true:

- If a vector $v \in V$ is orthogonal to everything in $U$, then it must be in $W$.

- Conversely, if a vector $v \in V$ is orthogonal to everything in $W$, then it must be in $U$.

Thus, one can replace “being in $U$” by “being orthogonal to all of $W$”. An analogous thing has happened here - instead of considering the relationship $a \leq b$ “directly”, as something out of $a$, we consider it “indirectly” via $z \leq a \implies z \leq b$, considering arrows into $a$. A relationship “orthogonal to” every arrow into $a$ must take the form of an arrow out of $a$.

A dual statement also holds by considering the other direction of comparison predicates:

So, a relationship “orthogonal to” every arrow out of $b$ must take the form of an arrow into $b$, because of reflexivity and transitivity.

This gives us some explanation of our trick of “following the identity” from before, as allowing us to interconvert between the “active” and “passive” perspectives of objects and relationships in an ordered set. In the case of $\text{gcd}(a, b, c) = \text{gcd}(\text{gcd}(a, b), c)$, antisymmetry shows that it suffices to prove inequalities both ways - and by viewing these inequalities “actively”, it suffices to prove $d \mid \text{gcd}(a, b, c) \iff d \mid \text{gcd}(\text{gcd}(a, b), c)$. In fact, this is generally true:

$a \leq b$ and $b \leq a$ in a preorder $X$ if and only if $\forall x \in X, x \leq a \iff x \leq b$, and if and only if $\forall x \in X, a \leq x \iff b \leq x$. For a partial order, we may replace the first condition by $a = b$, using antisymmetry.

However, it doesn’t get us all the way there. The universal property of minimum says that $x \leq \min(a, b) \iff x \leq a \text{ and } x \leq b$. While the left-hand side is a standard comparison predicate, the right-hand side is not - we’ve taken a conjunction of two of them. This gives us a hint that a little more flexibility is required…

Virtual Objects

One advantage of the “does” perspective is that it often allows you to generalise beyond the behaviour you see in the “is” world. For example, you can identify a function $f$ by what it “does” to other functions $g$, via the map $g \mapsto \int_{\mathbb{R} } f(x) g(x) dx$ (ignoring issues of convergence for now). We can then generalise to distributions, which are defined purely by what they “do” to other functions. More precisely, a distribution $\alpha$ is a functional $g \mapsto \alpha(g)$ which mimicks some of the properties of integration functionals, like linearity.

We can do a similar thing with ordered sets! Sometimes it’s helpful to consider “virtual objects” that aren’t directly part of our set $X$, but can nonetheless be compared to elements of $X$ in some way. A good example to keep in mind is real numbers and rational numbers:

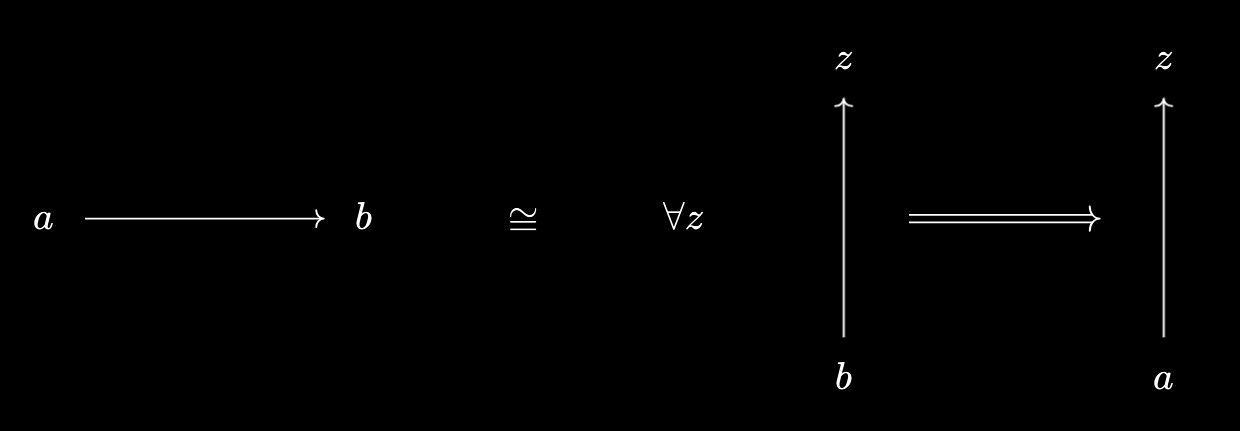

Indeed, the whole idea of Dedekind cuts, as a construction of real numbers, is to view them as “virtual” numbers that may be probed by/compared with ordinary rational numbers, via a comparison predicate “$q \leq \pi$”. We then axiomatise the properties that such a virtual comparison predicate needs to satisfy, and identify $\mathbb{R}$ with the set of valid comparison predicates (alternatively, by turning predicates into subsets, with the set of dedekind cuts).

In general, these virtual objects $v$ are defined purely by what they do, how they interact with elements of our base ordered set $X$. There are two ways we can specify them:

- A virtual object over our ordered set $X$, via a virtual comparison predicate $p(x) = (x \prec v)$

- A virtual object under our ordered set $X$, via a virtual comparison predicate $q(x) = (v \prec x)$

Another example of a virtual object is a collection of objects from our base ordered set. For example, we can consider the pair $(a, b)$ as a virtual object over $X$, a “cloud” of two objects that we can probe by objects from our base set. In this case, we define $x \prec (a, b)$ by $x \leq a \text{ and } x \leq b$, as a predicate. It also works as a virtual object under $X$ by defining $(a, b) \prec x$ by $a \leq x \text{ and } b \leq x$.

What properties does such a virtual predicate need to satisfy? There’s not really a way to make sense of “reflexivity”, since the whole point is that $v$ might not be an object of our ordered set. However, we can make sense of transitivity! Namely, if $x \prec v$ and $y \leq x$, then we should require that $y \prec v$ as well - in terms of the virtual predicate, this says $p(x) \text{ and } y \leq x \implies p(y)$ for virtual objects over $X$. Similarly, if $v \prec x$ and $x \leq y$, we should have $v \prec y$ too, meaning $q(x) \text{ and } x \leq y \implies q(y)$ for virtual objects under $X$. Much like distributions, we define virtual objects this way, as virtual predicates satisfying one of these consistency checks, depending on their type.

Formally, then, the definition of virtual objects is as follows:

A virtual object over $X$ consists of a predicate $p$ on $X$ such that $[y \leq x \text{ and } p(x)] \implies p(y)$. We may denote $p(x)$ by $x \prec v$ to write this condition as $[y \leq x \text{ and } x \prec v] \implies y \prec v$.

A virtual object under $X$ consists of a predicate $q$ on $X$ such that $[q(x) \text{ and } x \leq y] \implies q(y)$. We may denote $q(x)$ by $v \prec x$ to write this condition as $[v \prec x \text{ and } x \leq y] \implies v \prec y$.

Virtual Relationships

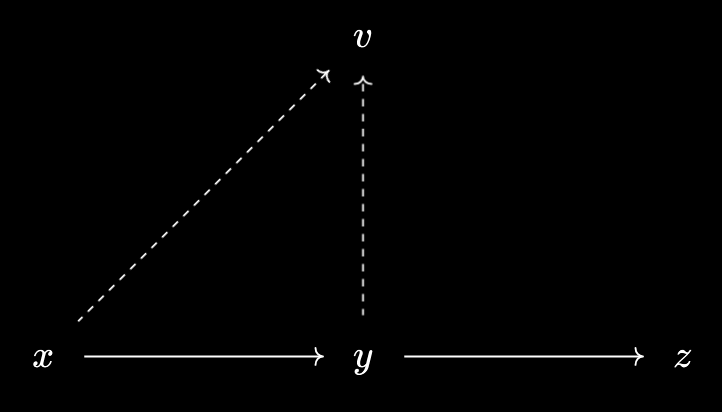

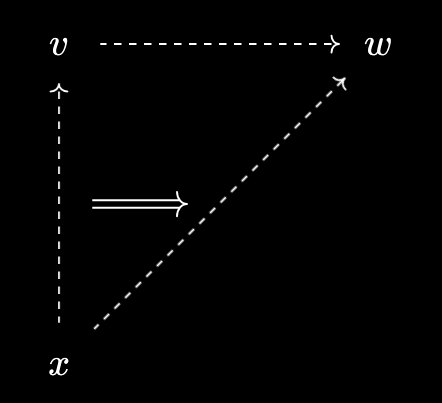

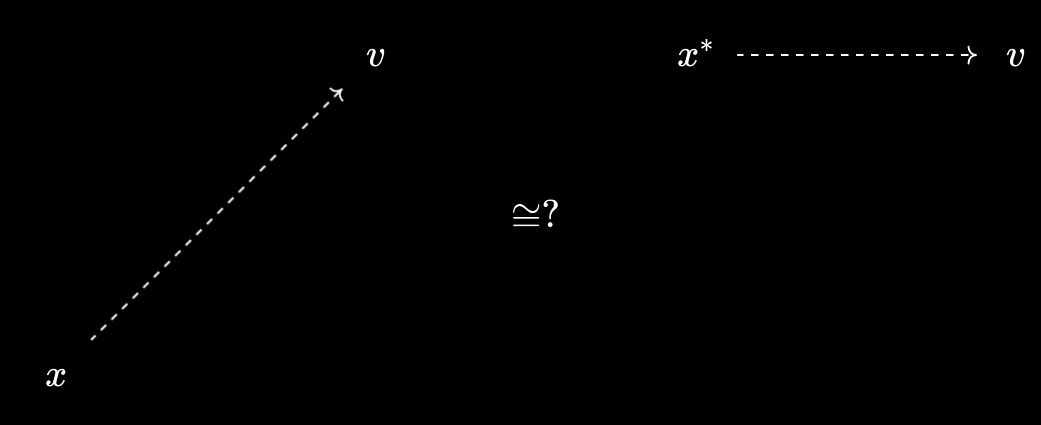

What might it mean to have a relationship between two virtual objects $v$ and $w$ over $X$? Say that we know what it means to say $x \prec v$ and $x \prec w$. While it’s unclear what $v \prec w$ “is”, it’s clearer what it should do - it’ll ensure that $x \prec v \implies x \prec w$, for $x$ an element of our base ordered set $X$:

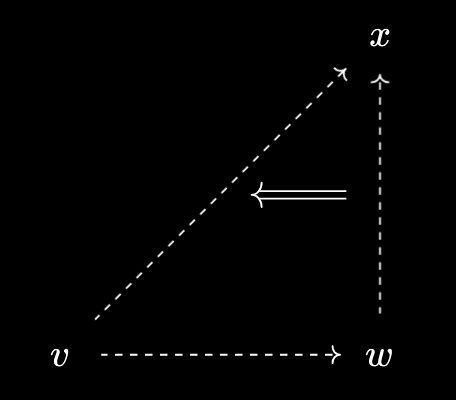

Thus, we define relationships between such virtual objects via implication of predicates. If $p_0, p_1$ are the predicates for $v, w$ respectively, then $v \prec w$ is defined to mean $p_0(x) \implies p_1(x)$. A dual statement holds for virtual objects under $X$:

In this case, if $q_0, q_1$ are the predicates for $v, w$ respectively, then $v \prec w$ is defined to mean $q_1(x) \implies q_0(x)$.

This new ordering on virtual objects (either over or under $X$) is then reflexive and transitive, which you can verify as an exercise. Thus, it “extends” the original ordered set by adding in all virtual objects. But where are the elements of our original ordered set? Well, it turns out we can also view them as virtual objects!

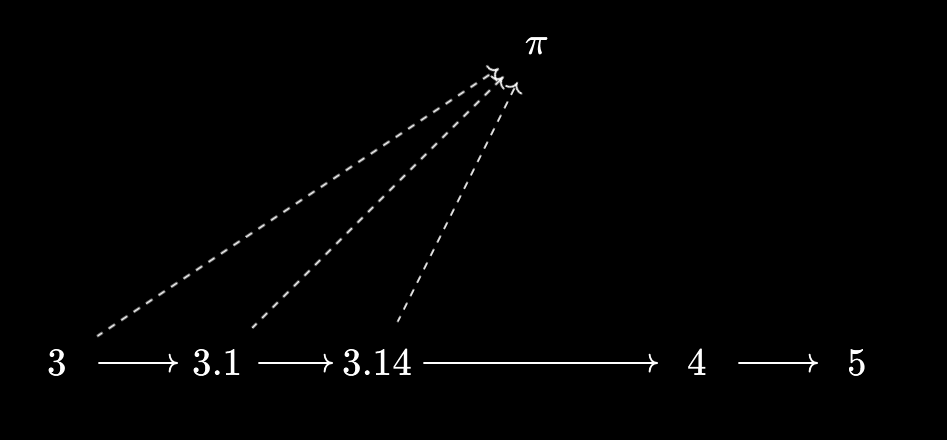

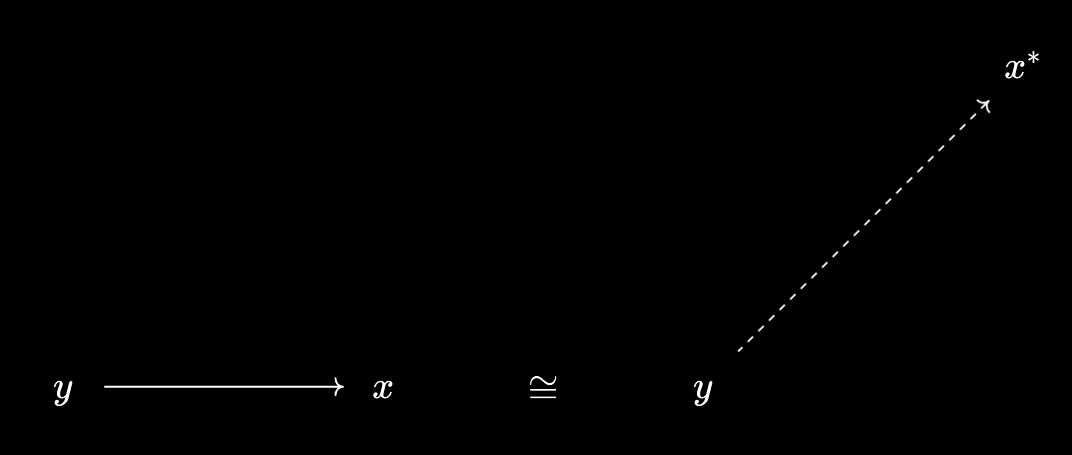

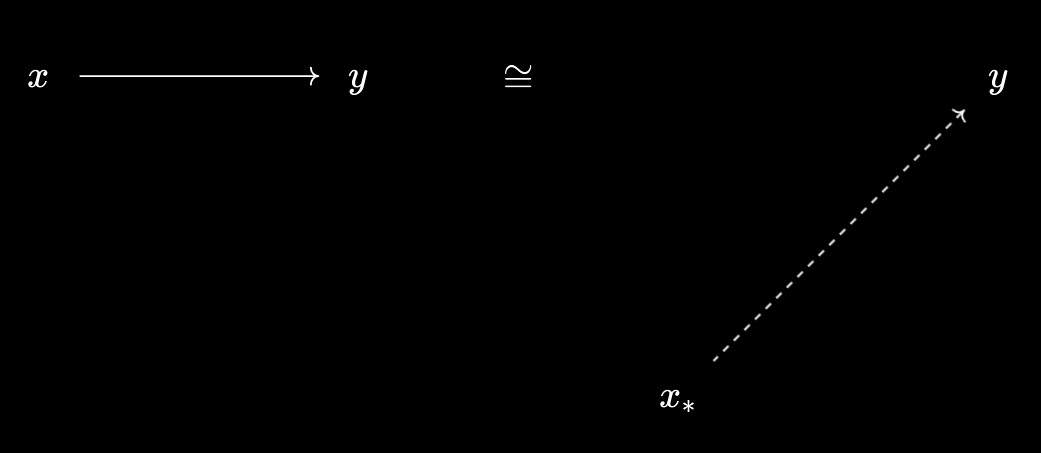

Namely, any $x \in X$ defines a virtual object \(x^*\) over $X$ just with its comparison predicate, with \((y \prec x^*) := y \leq x\). Dually we get a virtual \(x_*\) under $X$ with \((x_* \prec y) := x \leq y\). I like to think of these as “raising” and “lowering” the objects of $X$ to promote them to virtual objects over/under $X$, with any relationships coming along for the ride:

Now, though, we appear to have a potential for confusion. Given an object $x$ and a virtual object $v$ over $X$, we can compare them directly by $x \prec v$, or indirectly by $x^* \prec v$:

However, it turns out that, thankfully, these are equivalent! Continuing the visual metaphor, we may “raise” and “lower” the relationships that $x$ has with other virtual objects. In fact, this statement is precisely the Baby Yoneda Lemma.

(Baby Yoneda Lemma): Let $X$ be a preorder, $x \in X$, and $v$ a virtual object over $X$. Then $x \prec v$ if and only if $x^* \prec v$. Dually, if $w$ is a virtual object under $X$, then $w \prec x$ if and only if $w \prec x_*$.

The proof is simple. $x^* \prec v$ is equivalent to the statement $\forall y \in X . (y \prec x^*) \implies (y \prec v)$, by definition. And that’s equivalent to $\forall y \in X. (y \leq x) \implies (y \prec v)$. Transitivity guarantees that $x \prec v$ is sufficient for this to hold - it’s what the relationship $x \prec v$ “does”, after all! Conversely, if this implication holds, then we can “follow the identity” by substituting $y = x$ to conclude $x \prec v$, so $x \prec v$ is also necessary.

So we see that, at least for preorders, the yoneda lemma is just a manifestation of “is-does duality”. We can view the relationship $x \prec v$ passively, or we can view it actively as $x^* \prec v$, and these are completely equivalent perspectives.

Applications

Let’s take the implication $x \leq \min(a, b) \implies x \leq a \land x \leq b$. Viewing $(a, b)$ as a virtual object over our preorder, we see that this is just the statement $\min(a, b)^* \prec (a, b)$. By Yoneda, this is equivalent to saying $\min(a, b) \prec (a, b)$ i.e. $\min(a, b) \leq a$ and $\min(a, b) \leq b$! Note that we also have $(a, b) \prec \min(a, b)^*$, which we can’t apply Yoneda to since it’s the “wrong direction”.

Now for floor and ceiling. Instead of viewing a real number $r$ as a virtual object on $\mathbb{Q}$, we can also view it as a virtual object on $\mathbb{Z}$, with the predicates $n \prec r$ and $r \prec n$ defined using the inclusion of $\mathbb{Z}$ into $\mathbb{R}$. So, $n \prec r$ is defined as $\iota(n) \leq r$, and $r \prec n$ as $r \leq \iota(n)$, for $\iota : \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{R}$ the inclusion. These realise $r$ as a virtual object over/under $\mathbb{Z}$, respectively.

It turns out that we can always represent these virtual objects by actual objects! Taking $\pi$ as an example, $n \prec \pi \iff n \leq 3$, and $\pi \prec n \iff 4 \leq n$. Thus, if we view $\pi$ as a virtual object over $\mathbb{Z}$, we may identify it with $3$, since we have \(\pi^* \prec 3^*\) and \(3^* \prec \pi^*\), which by yoneda says \(3 \prec \pi^*\). On the other hand, if we view $\pi$ as a virtual object under $\mathbb{Z}$, we can identify it with $4$, since we have \(4_* \prec \pi_*\) and \(\pi_* \prec 4_*\), which by yoneda says \(\pi_* \prec 4\).

For a general real number $r$, these correspond to “floor” and “ceiling”. Viewing $r$ as a virtual object over $\mathbb{Z}$ identifies it with $\lfloor r \rfloor$, and viewing it as a virtual object under $\mathbb{Z}$ identifies it with $\lceil r \rceil$.

A similar story happens for “interior” and “closure” operations. We can view an arbitrary subset $S$ of a topological space as a virtual object over the collection of open sets, defining $U \prec S$ if and only if $\iota(U) \subset S$, where $\iota$ is the inclusion of open subsets into all subsets. The point of the interior is to represent $U \prec S$ by an ordinary open set $\text{Int}(S)$, so that $\iota(U) \subset S \iff U \subset \text{Int}(S)$. You can then apply Yoneda by “following the identity” to show $U \subset \text{Int}(\iota(U))$ and $\iota(\text{Int}(S)) \subset S$.

Similarly, taking the inclusion of closed sets into all subsets, we can view $S$ as a virtual object under the collection of closed sets, defining $S \prec C$ if and only if $S \subset \iota(C)$. Then the point of the closure is to represent $S$ by an ordinary closed set $\bar S$, so that $S \subset \iota(C) \iff \bar S \subset C$.

We’ve seen a similar construction relating image and preimage, in fact. Given a function $f : X \to Y$, we get a monotone preimage map $f^{-1} : P(Y) \to P(X)$. This lets you view a subset $A \subset X$ as a virtual object under $P(Y)$, defining $A \prec B \iff A \subset f^{-1}(B)$ for $B \subset Y$. The direct image then lets you represent this virtual object by an actual object - the direct image $f(A) \subset Y$! Since we know $f(A) \subset B \iff A \subset f^{-1}(B)$. As an exercise, can you represent the virtual object $B \prec A := f^{-1}(B) \subset A$ of $A$ over $P(Y)$ as an actual object $f^\sharp(A) \in P(B)$? I.e. such that $f^{-1}(B) \subset A \iff B \subset f^\sharp(A)$.

Finally, here’s a trick you can use to compute the actual object corresponding to a virtual object, if it exists. For the closure of $S$, we want $S \subset \iota(C) \iff \bar S \subset C$, for $C$ a closed set. How about $C \subset \bar S$? Using yoneda, we can view this “actively” as saying $\forall C’ \text{ closed }, \bar S \subset C’ \implies C \subset C’$. This is equivalent to $\forall C’ \text{ closed }, S \subset \iota(C’) \implies C \subset C’$. Thus, if $C \subset \bar S$ is equivalent to saying $C$ is contained within every $C’$ with $S \subset \iota(C’)$.

But we can “package” all those inclusions together into a single inclusion! It’s the same as saying $C \subset \bigcap_{C’ \text{ closed, such that } S \subset \iota(C’)} C’$. And indeed, the right-hand side is the usual construction of the closure of a subset.

The same sort of construction works for “closures” of subsets to subgroups, or to subspaces, or to topologies, by taking the intersection of all subgroups/subspaces/topologies containing your object. A dual construction works for “interior” operators - this is how we obtain the characterisation of $\lfloor x \rfloor$ as the largest integer $\leq x$, and $\lceil x \rceil$ as the smallest integer $\geq x$. They all come from taking the universal property the “wrong way”, and then using Yoneda to view it “actively”.

Closing Thoughts

The paper “How to Represent Non-Representable Functors” was a big influence for this post.

I’ve been wanting to make this post for a while. As far as I can tell, there’s no other resource which seems to explain Yoneda via the perspective of “is-does duality”, at least not this explicitly. Of course, it is a term I made up, so that might be a part of it…

Still, my hope is that this more “physicsy” way to view Yoneda can help you to understand it. In a strong sense, Yoneda is about the equivalence of the “is” and “does” perspectives - and much like physics, category theory tends to care a lot more about what objects “do” than what they “are”. That’s the whole idea behind universal properties, for example - instead of specifying what the object “is” directly, they give you a blueprint for what you want your object to do! Then you can investigate whether there actually is any object matching the specified blueprint, representing the virtual object by a real one.