Baby Yoneda 2: Representable Boogaloo

Matching Blueprints

Before embarking on a large construction project, it helps to have a blueprint of the structure you want to build. This gives you an idea of what materials are required, how much time and money are needed, and how you might organise the process of constructing the building. Blueprints are also significantly easier to change than actual physical structures; so if you’re in more of an exploratory phase, where you need the freedom to update ideas and specifications on-the-fly, blueprints are the way to go.

In many ways, the virtual objects we met in The Baby Yoneda Lemma play the same role. They can serve as “blueprints” for actual objects you want to build, guiding the construction process for these objects, and giving you a better idea what these constructions are meant to do. In today’s article, we’ll explore this in more detail, learning precisely what it means to represent a virtual object by an actual object.

Let’s remind ourselves of the relevant definitions.

A preorder is a set $X$ together with a relation $\leq \space \subset X \times X$ that is reflexive and transitive, meaning $\forall x \in X, x \leq x$ and $\forall x, y, z \in X, [x \leq y \text{ and } y \leq z] \implies x \leq z$.

We will refer to these as “ordered sets” in what follows.

A virtual object over an ordered set $X$ consists of a predicate $p$ on $X$ such that $[y \leq x \text{ and } p(x)] \implies p(y)$. We may denote $p(x)$ by $x \prec v$ to write this condition as $[y \leq x \text{ and } x \prec v] \implies y \prec v$

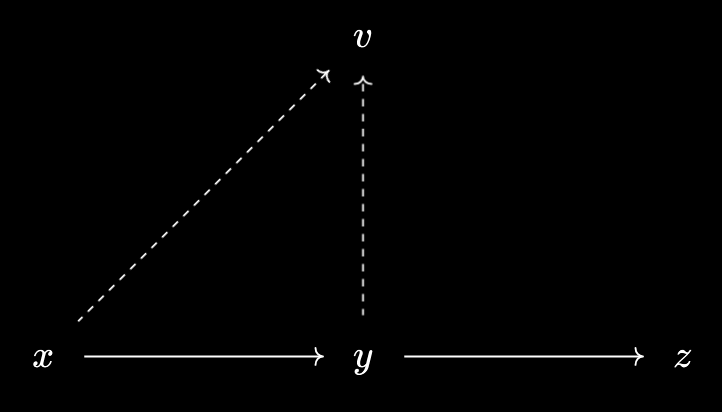

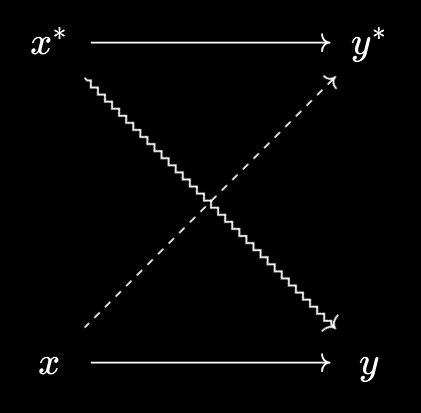

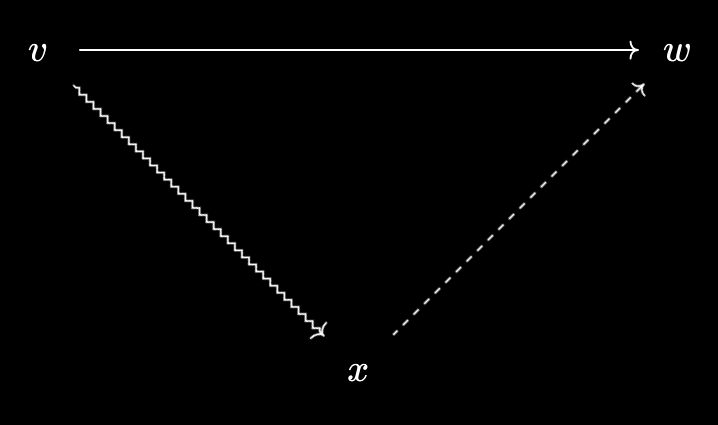

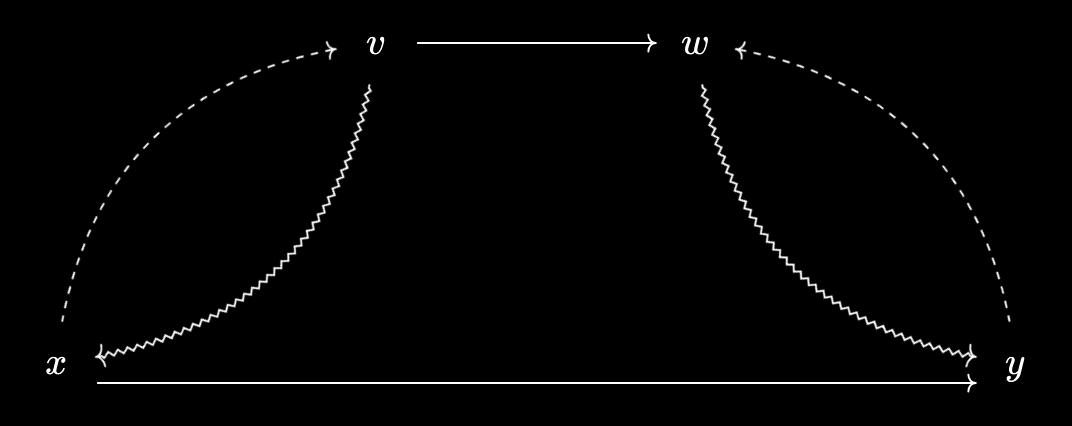

These also have a natural visualisation, where we represent the relation $a \leq b$ by an arrow from $a$ to $b$, and $x \prec v$ by a dashed arrow from $x$ to $v$:

There is also a corresponding dual definition:

A virtual object under an ordered set $X$ consits of a predicate $q$ on $X$ such that $[q(x) \text{ and } x \leq y] \implies q(y)$. We may denote $q(x)$ as $v \prec x$ to write this condition as $[v \prec x \text{ and } x \leq y] \implies v \prec y$.

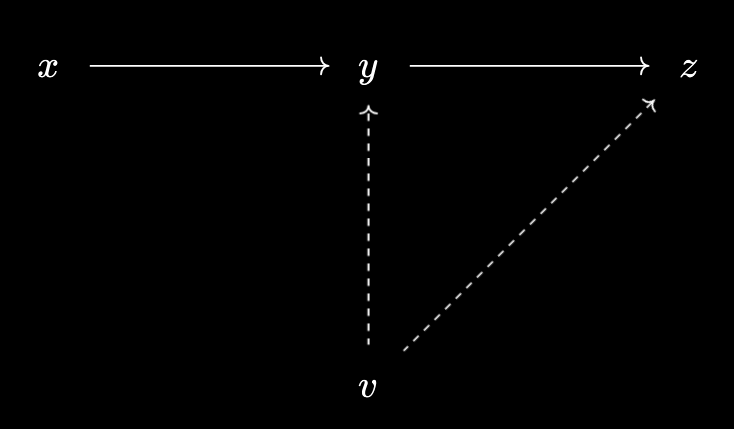

And a corresponding dual visualiation:

Raising and Lowering (Virtual) Objects

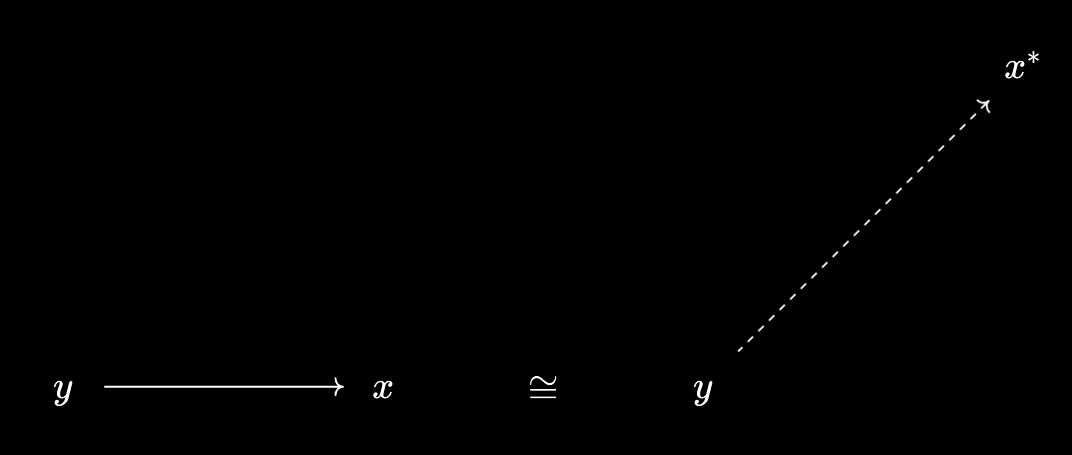

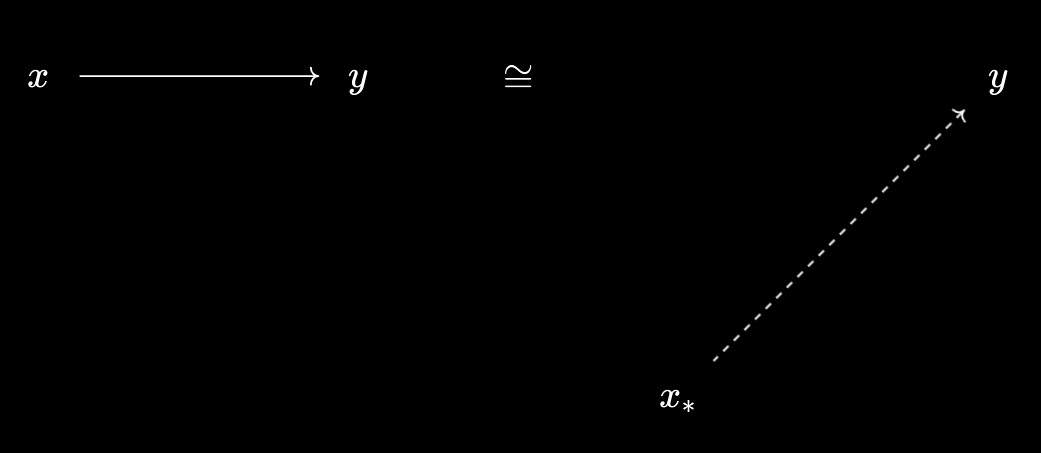

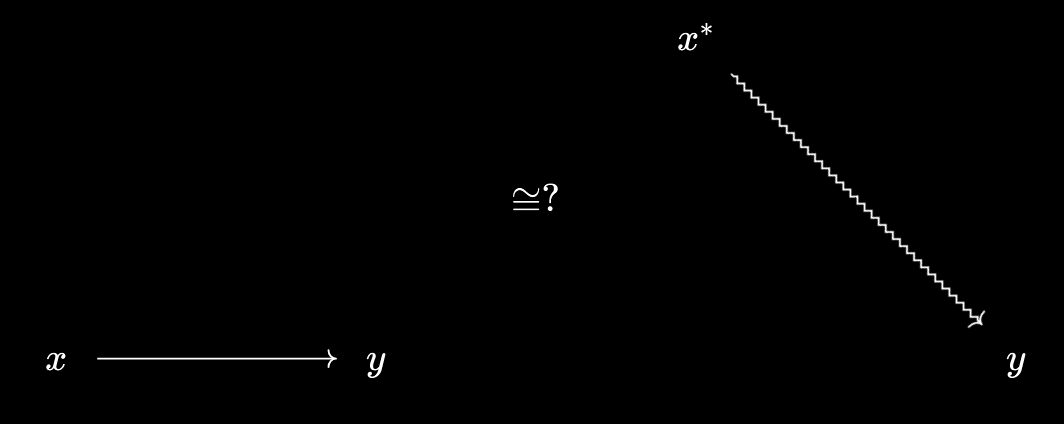

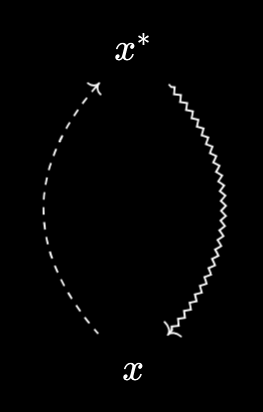

As we saw in the previous article, it’s possible to “raise” an element $x \in X$ of our ordered set to become a virtual object \(x^*\) over $X$, or “lower” it to become a virtual object \(x_*\) under $X$, with any relationships coming along for the ride:

As the pictures demonstrate, we define \(y \prec x^* := y \leq x\), and \(x_* \prec y := x \leq y\). However, you may have noticed that I’ve cheated slightly in saying that any relationships can come along for the ride! What happens if we try to raise $x$ in this diagram?

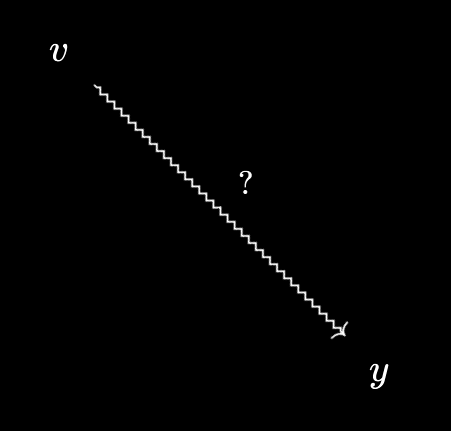

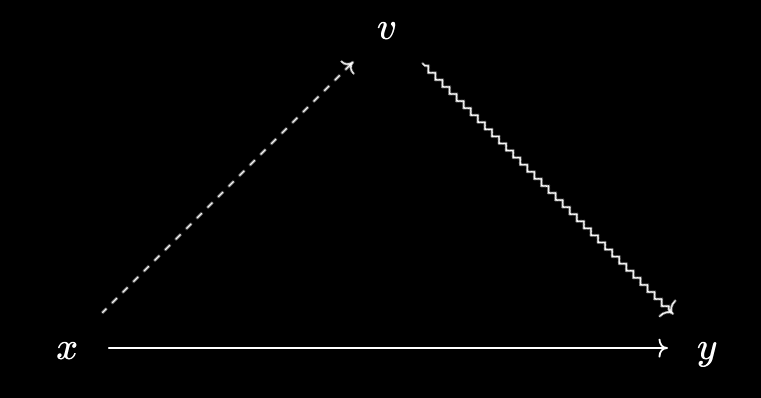

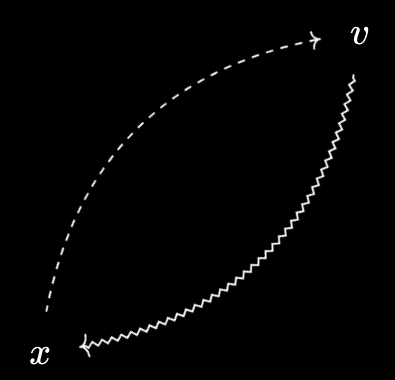

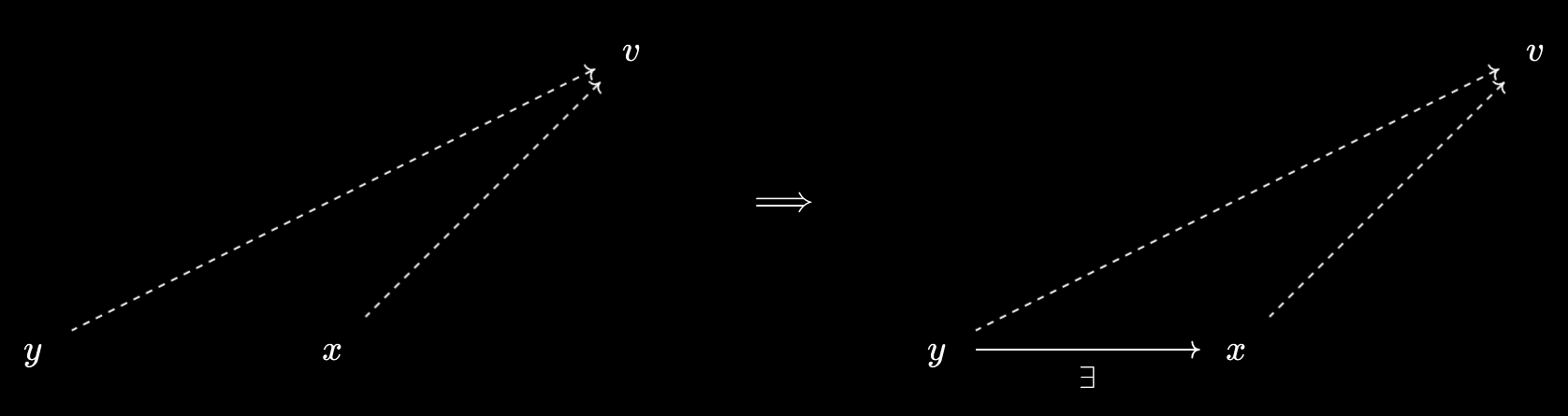

Now we have an arrow from a virtual object over $X$ to an element of $X$. If you comb through my last post, you’ll see I carefully avoided having to define such a notion! We know what it means to have an arrow between elements of $X$, or from an element of $X$ to a virtual object over $X$, or between two virtual objects over $X$. This last case, however, is not quite as clear:

This is where the Yoneda philosophy can help. Currently, it’s not so clear what an arrow from $v$ to $y$ “is”. So instead, we can try to investigate what it should do, and define it in terms of that!

As suggested by the diagram, whatever such an arrow “is”, it should still allow transitivity to hold. So, if we have an arrow from $v$ to $y$, and we also know that $x \prec v$, then we should be able to conclude $x \leq y$. Thus, what this relationship does is let us conclude $\forall x \in X, x \prec v \implies x \leq y$.

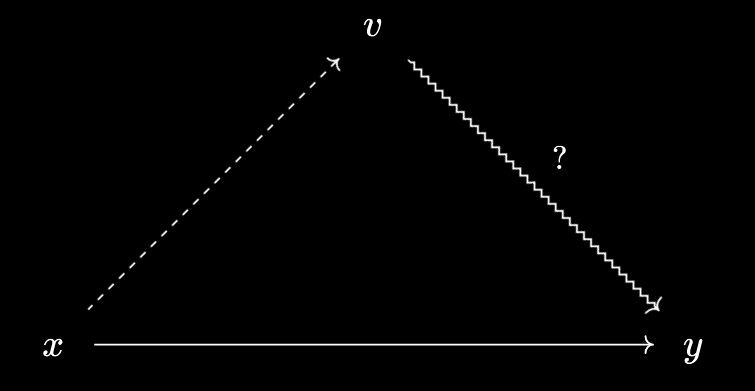

But that looks a little familiar - it seems like a relationship between virtual objects! In fact, it’s precisely the relationship $v \prec y^*$:

You can visualise this as “raising” $y$ from the previous diagram to correct the direction of the relationship. (Of course, if I was better at animation, you’d be able to actually see this rather than just being asked to visualise it…)

So, if $v$ is a virtual object over $X$, we define $v \prec y$ to mean $v \prec y^*$. There are two important things to notice about this definition:

- This allows you to regard any virtual object over $X$ as a virtual object under $X$. We turn $v$ into \(v_*\) under $X$ defined by \(v_* \prec y := v \prec y^*\). In fact, we’ve glimpsed a toy example of a much grander duality, known as Isbell Duality.

- This is also consistent with the existing order on the elements of $X$. Raising $x$ to \(x^*\), we have \(x^* \prec y\) defined to be \(x^* \prec y^*\), which by Baby Yoneda is if and only if \(x \prec y^*\), which by definition is if and only if \(x \leq y\). So all 4 “versions” of this relationship are equivalent to each other.

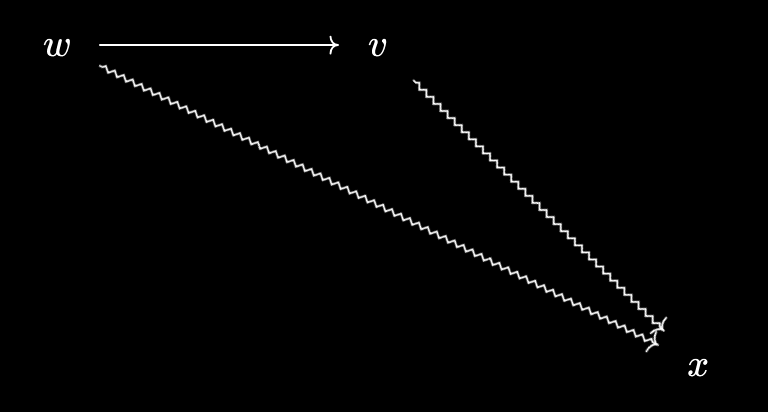

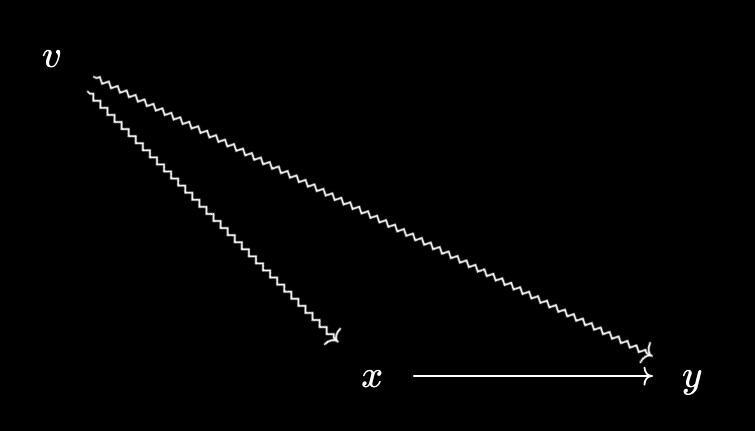

We now have full freedom in raising and lowering objects of $X$. It’s also important to check these new relationships don’t break transitivity. There are four diagrams for this we should check:

- If $v$ is a virtual object over $X$, then $[x \prec v \text{ and } v \prec y] \implies x \leq y$. To prove this, note that \(v \prec y := v \prec y^*\), so \([x \prec v \text{ and } v \prec y] \implies x \prec y^*\) by transitivity. But by definition, this means $x \leq y$, as required.

- If $w, v$ are virtual objects over $X$, then $[w \prec v \text{ and } v \prec x] \implies w \prec x$. To prove this, note that \(v \prec x := v \prec x^*\), so \([w \prec v \text{ and } v \prec x] \implies w \prec x^*\) by transitivity. But by definition, this means $w \prec x$, as required.

- If $v$ is a virtual object over $X$, then $[v \prec x \text{ and } x \leq y] \implies v \prec y$. To prove this, note that \(v \prec x := v \prec x^*\). We can then chain this with \(x^* \prec y^*\) to conclude \(v \prec y^*\). But by definition, this means $v \prec y$, as required.

- If $w, v$ are virtual objects over $X$, then $[w \prec x \text{ and } x \prec v] \implies w \prec v$. To prove this, note that \(w \prec x := w \prec x^*\). Moreover, by Baby Yoneda, $x \prec v$ implies \(x^* \prec v\). So we can chain these together to conclude $w \prec v$, as required.

Finally, this gives us a new mechanism to interpret the Baby Yoneda Lemma, in a way that rather explicitly exhibits the “is-does duality” I was talking about last article. Namely, with these new relationships, $x$ and \(x^*\) are equivalent objects!

The relationship \(x \prec x^*\) comes from “reflexivity”, i.e. lifting the identity $x \leq x$. And the relationship \(x^* \prec x\) comes from the same identity, just by lifting the other side!

As you may recall, Baby Yoneda says that \(x \prec v \iff x^* \prec v\). We can now interpret this as a natural consequence of $x$ and \(x^*\) being equivalent objects, and applying transitivity accordingly. Thus, one can really view the Baby Yoneda Lemma as the statement “what an object is is equivalent to what an object does”, in a perfectly rigorous sense!

Representing Virtual Objects

The definition of a representation of a virtual object is now pretty straightforward, although the notions we developed in the previous section will end up helping extensively with working with and interpreting it.

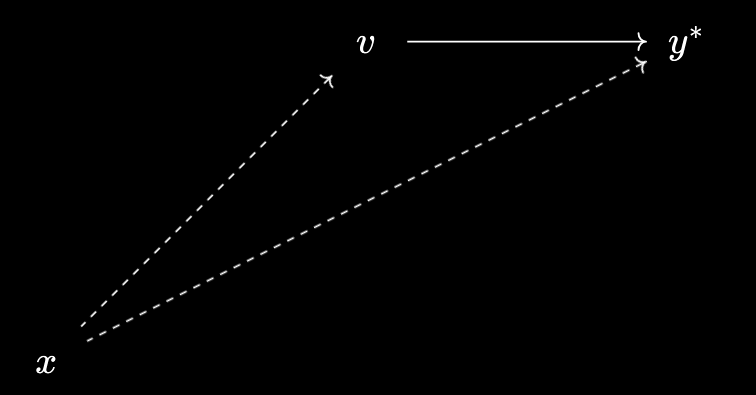

A representation for a virtual object $v$, either over or under $X$, consists of an object $x \in X$ with $v \prec x$ and $x \prec v$, i.e. an actual object it is equivalent to. A virtual object is representable if it has at least one representation.

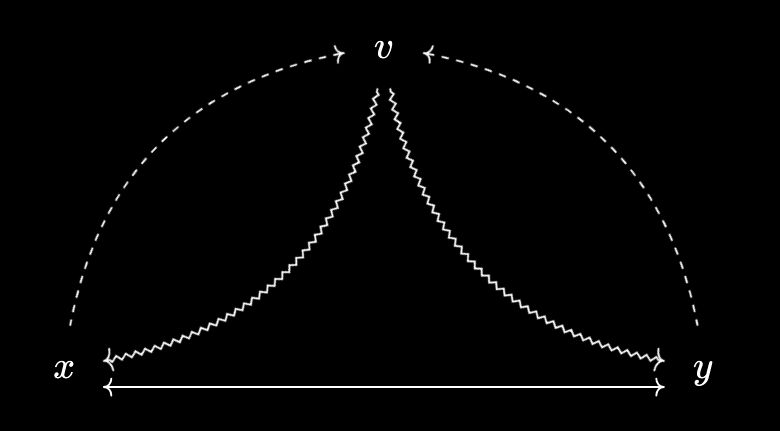

For virtual objects over $X$, we have the following diagram:

As an example, for every $x \in X$, \(x^*\) is representable by $x$ - indeed, this is a rephrasing of Baby Yoneda. Dually, \(x_*\) is also representable by $x$.

There are a few important properties of such representations:

- Representations are unique up to equivalence. That is, if both $x, y \in X$ work as representations for a virtual object $v$, then $x$ and $y$ are equivalent in the sense that $x \leq y \text{ and } y \leq x$. (In a partial order, this would imply $x = y$, so that representations are strictly unique.)

This is easy to see from the diagram by simply following the arrows.

This is easy to see from the diagram by simply following the arrows. - Representations respect relationships. That is, if $x$ is a representation for $v$ and $y$ is a represention for $w$, then $v \prec w \iff x \leq y$. Again, this is easy to see visually - the equivalences let us interconvert relationships involving a virtual object and its representation.

- Representations are universal relationships. We can alternatively view a representation of a virtual object $v$ over $X$ as an object $x \in X$ such that $x \prec v$ and whenever $y \prec v$, we must have $y \leq x$. In this sense, $x$ has a universal arrow into $v$ - every other such arrow differs from a standard arrow into $x$. This connects the notion of representation with the usual formulation of universal properties!

Compare the last bulletpoint with the definition of $\sup S$ as “an upper bound of $S$ such that, if $u$ is any other upper bound of $S$, then $\sup S \leq u$”.

Closing Thoughts

Hopefully you’re a bit more convinced that “is-does duality” is at the heart of the Yoneda Lemma, or at least the baby version (for now). The diagrams I’ve used in this post carry over almost seamlessly to the full yoneda lemma, with a few important modifications - the arrows obtain labels, and we start needing to worry about naturality. But that’ll be a story for another day!

I’m planning to continue this “Baby Yoneda” series with a few more articles. I want to do one explaining some of the most important representable virtual objects - joins and meets. Adjunction and Kan Extensions also have interesting interpretations even at the level of ordered sets, so it may be useful to explain these more thoroughly in this context.