Baby Yoneda 4: Adjunctions at the Function

Definition by Doing

The main idea I’ve wanted to emphasise again and again in this “Baby Yoneda” series is the concept of is-does duality:

The Yoneda Lemma is the statement that “what something is is equivalent to what something does”.

This means that, if we’re in a situation where it’s not entirely clear what something “is”, we can instead try to specify what we want it to do, a virtual object that acts as a blueprint for our desired construction. This is the philosophy behind universal properties, which specify what objects do, actively, over what they are, passively.

In Baby Yoneda 3, we saw one of the most important examples of a universal property: meets and joins. These act as “packagers” which bundle together a subset of elements from our ordered set, in a way that also allows you to bundle relationships together. And as we discussed there, they can be used to help compute representations of any virtual object!

Today we are going to meet another important kind of universal property: that of an adjunction. The overarching idea is the same - to define something by what it does - but the method by which we achieve this will be a little different. Instead of packaging a subset, we’re going to leverage existing relationships to define a family of virtual objects, and ask for these to be represented by actual objects. If you’ve done a bit of order theory before, you’ll recognise these as galois connections.

Floor and Ceiling

Some of the earliest examples of virtual objects we met were considering real numbers as virtual objects over the rationals:

In general, given a real number $r \in \mathbb{Q}$ we can define a virtual object over $\mathbb{Q}$ by $q \prec r := q \leq r$, and a virtual object under $\mathbb{Q}$ by $r \prec q := r \leq q$, where we use the ordering on $\mathbb{R}$. To have a representation of $r$ over $\mathbb{Q}$ is to find some rational $s \in \mathbb{Q}$ such that $q \leq r \iff q \leq s$, and dually for viewing $r$ as a virtual object under $\mathbb{Q}$. In this case, the density of the rationals in $\mathbb{R}$ shows us that $r$ cannot be representable unless it is already rational!

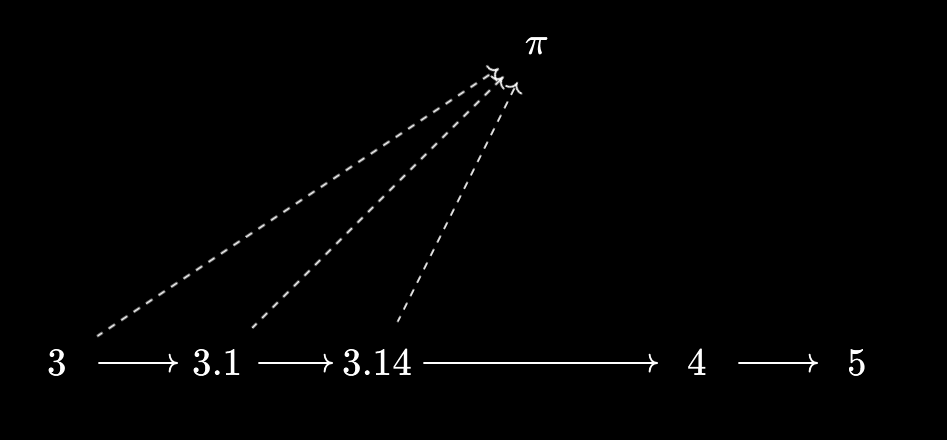

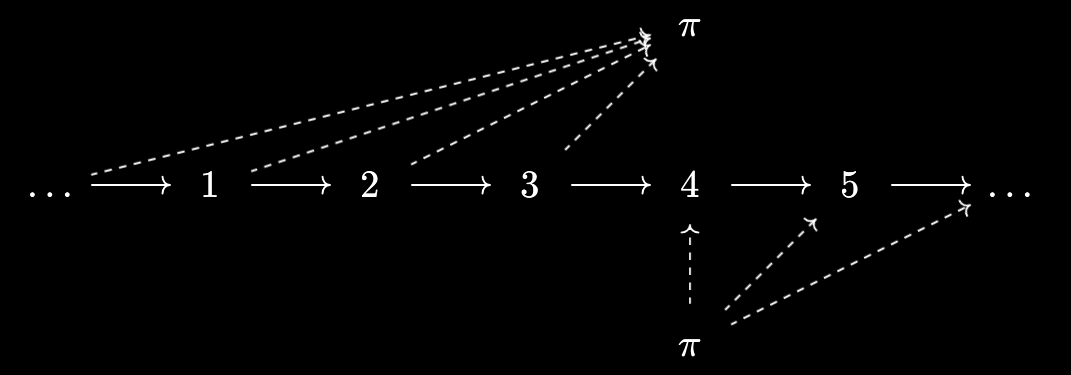

So, what happens if we restrict attention to a more “discrete” subset of the real numbers - say, the integers? We can still see $\pi$ as a virtual object over the integers, by defining $n \prec \pi := n \leq \pi$:

I’ve also illustrated viewing $\pi$ as a virtual object under the integers, defining $\pi \prec n := \pi \leq n$. Unlike the previous case, these virtual objects are indeed representable! For $n \in \mathbb{Z}$, we have $n \prec \pi \iff n \leq 3$, and $\pi \prec n \iff 4 \leq n$. We recognise $3$ as the join of all $n$ with $n \prec \pi$, and $4$ as the meet of all $n$ with $\pi \prec n$, as expected from the representation formulae we derived in Baby Yoneda 3.

For a general real number $r \in \mathbb{R}$, much the same story plays out. In this case, we find that $n \prec r \iff n \leq \lfloor r \rfloor$, and $r \prec n \iff \lceil r \rceil \leq n$. We see that what floor and ceiling “do” is represent the virtual relationships $n \prec r$ and $r \prec n$ as actual relationships!

These define monotone maps $\lfloor \cdot \rfloor, \lceil \cdot \rceil : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{Z}$. We have a natural monotone map $\iota : \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{R}$ going the other way too, by just including integers into real numbers. This sets up what’s called an adjunction:

$\iota(n) \leq r \iff n \leq \lfloor r \rfloor, r \leq \iota(n) \iff \lceil r \rceil \leq n$

Based on the direction of the arrows, we say that floor is the right adjoint of inclusion, and ceiling is the left adjoint of inclusion. Dually, inclusion is the left adjoint of floor, and is the right adjoint of ceiling. This example captures the essence of what adjunctions are - what floor and ceiling do is represent existing relationships between integers and real numbers by ordinary relationships between integers.

There are other monotone maps $f : \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{R}$ we could consider, such as a linear map $f(n) = an + b$. What would it mean to have left and right adjoints for these? Let’s say we choose $f(n) = 3n + 1$, for concreteness. Then:

- For the left adjoint $L(r)$, what we want $L(r)$ to do is represent $r \leq f(n)$, so that $L(r) \leq n \iff r \leq 3n + 1$. But $r \leq 3n + 1 \iff \frac{r - 1}{3} \leq n$, whence we can use the previous adjunction to show that’s $\iff \lceil \frac{r - 1}{3} \rceil \leq n$. So the left adjoint is $L(r) = \lceil \frac{r - 1}{3} \rceil$.

- For the right adjoint $R(x)$, what we want $R(x)$ to do is represent $f(n) \leq x$, so that $n \leq R(x) \iff 3n + 1 \leq x$. We can use similar steps as before to show that’s equivalent to $n \leq \lfloor \frac{x - 1}{3} \rfloor$. So the right adjoint is $R(x) = \lfloor \frac{x - 1}{3} \rfloor$.

The case for a general monotone map $f : \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{R}$ is quite similar. We can use the technology developed in Baby Yoneda 3 to capture this:

- For the left adjoint, we view a real number $r \in \mathbb{R}$ as a virtual object under $\mathbb{Z}$, defining $r \prec n := r \leq f(n)$.

- Following the example of $\pi$, to compute a candidate representation for $r$, we should take the meet of all $n$ above it - so, \(\inf \{n \in \mathbb{Z} \mid r \leq f(n)\}\).

- Since $f$ is monotone, this set must be of the form \(\{n \in \mathbb{Z} \mid N \leq n\}\) for some $N \in \mathbb{Z}$, unless the set is empty or all of $\mathbb{Z}$.

- So long as the set is a nonempty proper subset of $\mathbb{Z}$, we can take its minimum (same as infimum) to define the left adjoint at $r$, so that \(L(r) := \min \{n \in \mathbb{Z} \mid r \leq f(n)\}\).

A similar story holds for the right adjoint, by taking the maximal $N$ with $f(N) \leq r$. I like floor and ceiling because they’re quite simple but still illustrative examples of adjoints; in some situations, you can think of adjoints as “approximate inverses”, and floor/ceiling approximate a real number by an integer in two different ways. Floor comes “from the left”, looking at integers below your real number, while ceiling comes “from the right”, looking at integers above your real number.

It’s high time we formalised a definition of adjunction. Here’s our first try:

An adjunction between a pair of preordered sets $A$ and $X$ is a pair of monotone maps $L : A \to X$ and $R : X \to A$ with $L(a) \leq x \iff a \leq R(x)$.

Note that if $L$ and $R$ are actual inverses of each other, then $L(a) \leq x \iff R(L(a)) \leq R(x) \iff a \leq R(x)$, so they form an adjunction. Thus, adjoints generalise true inverses!

Number-Theoretic Adjunctions

Addition

Armed with our new definition, let’s see if we can try to find some other examples of adjunctions with numerical functions. Say we take $\mathbb{N}$ (including $0$) as our ordered set, and consider the monotone map $f(n) := n + 3$. What would left and right adjoints look like, if they exist?

Let’s start with a left adjoint. We want some monotone map $g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}$ such that $g(a) \leq n \iff a \leq f(n)$, i.e. $g(a) \leq n \iff a \leq n + 3$. Passing to integers, we know that $a \leq n + 3 \iff a - 3 \leq n$. Now we can split into two cases:

- If $a \geq 3$, then $a - 3 \in \mathbb{N}$, so we can just set $g(a) = a - 3$

- If $a < 3$, then notice that $a \leq n + 3$ is always true, since $n + 3 \geq 3 > a$! So $a$, viewed as a virtual object under $\mathbb{N}$, must be $\leq$ all natural numbers. But this object is representable - we just use $0$. So in this case, we set $g(a) = 0$, recognising that $0 \leq n \iff a \leq n + 3$ since both sides are always true.

Thus, in general, the formula for the left adjoint is $g(a) = \max(0, a - 3)$. We see that this defines a kind of “predecessor” operation on the naturals - we keep stepping back by $1$ if we can, and stay at $0$ once we reach there. More generally, we have that:

$a \leq b + c \iff \max(0, a - b) \leq c$

For fixed $b$, we can view this as an adjunction with $a \mapsto \max(0, a - b)$ the left adjoint and $c \mapsto b + c$ the right adjoint. If it feels strange that we need to fix $b$, hold that thought! We’ll see later that there’s a nice uniform way to make sense of “families of adjunctions” like this.

So, predecessor is a left adjoint to addition. What about a right adjoint? Can we find some $h(a)$ such that $n + 3 \leq a \iff n \leq h(a)$? Passing to integers again suggests $n \leq a - 3$, so we split into cases again:

- If $a \geq 3$ then $a - 3 \in \mathbb{N}$, so we can define $h(a) = a - 3$ without issue.

- If $a < 3$, then $n + 3 \leq a$ is always false, since $n + 3 \geq 3 > a$. This would mean we’d need $n \leq h(a)$ to be always false, too. But that’s impossible, since $n \leq h(a)$ is true for at least $n = h(a)$!

We see that the right adjoint, unlike the left adjoint, cannot be globally defined. It works on the subset of $\mathbb{N}$ from $3$ onwards, but otherwise fails to exist. Thus, strictly speaking, $f$ does not have a right adjoint, though see later for a way to interpret this “partial adjoint” situation.

Overall, we’ve seen that the left adjoint to addition does exist, and takes the form of a predecessor operation. The right adjoint fails to exist globally, requiring the input to be at least $3$. This reflects a broader trend in the way adjoints tend to work - left adjoints are more “liberal” and “free” with their approximations, while right adjoints are more “conservative” and “restrictive” with theirs.

Multiplication

How about multiplication? Again, we’ll consider $f(n) := 3 \times n$, and attempt to find left and right adjoints.

For a left adjoint, we want $g(a) \leq n \iff a \leq 3 \times n$. Passing to real numbers, we know that $a \leq 3 \times n \iff \frac a3 \leq n$. Then we can use the ceiling adjunction to show $\frac a3 \leq n \iff \lceil \frac a3 \rceil \leq n$. Thus, $g(a) = \lceil \frac a3 \rceil$ works as a left adjoint - no case splitting required!

How about the right adjoint? Now we want $n \leq h(a) \iff 3 \times n \leq a$. Passing to real numbers, we know that $3 \times n \leq a \iff n \leq \frac a3$, and using the floor adjunction that’s $\iff n \leq \lfloor \frac a3 \rfloor$. Thus, $h(a) = \lfloor \frac a3 \rfloor$ works as a right adjoint. Seems we got lucky this time around!

So, at least with respect to the usual order on $\mathbb{N}$, multiplication has both left and right adjoints. They correspond essentially to division together with a “rounding” operation. Things become a little more interesting if we instead use the divisibility order on $\mathbb{N}$, where $a \mid b \iff \exists k \in \mathbb{N}, b = ka$. Note that, under this order, $1$ is an initial object and $0$ is a terminal object.

It turns out that multiplication has a left adjoint here; more precisely, we have the following (family of) adjunctions:

$n \mid km \iff \frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, k)} \mid m$

The proof goes as follows:

- First, it’s easier to establish a weaker lemma. If $r > 0$, then $a \mid b \iff ra \mid rb$. This is because $a \mid b \iff \exists k \in \mathbb{N}, b = ka \iff \exists k \in \mathbb{N}, rb = rka \iff ra \mid rb$.

- Then, since $\text{gcd}(n, k)$ divides both $n$ and $k$, we have that $n \mid km \iff \frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, k)} \mid \frac{k}{\text{gcd}(n, k)} m$

- But $\frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, k)}$ and $\frac{k}{\text{gcd}(n, k)}$ are coprime! So we can apply Euclid’s lemma to conclude $\frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, k)} \mid \frac{k}{\text{gcd}(n, k)} m \iff \frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, k)} \mid m$

So, for each fixed $k$, multiplication by $k$ has a left adjoint, namely $n \mapsto \frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, k)}$. Though, if you’ve been paying attention, you may have noticed I’ve done a little swindle - I didn’t check that the left adjoint was monotone! Later we’ll see why this is actually unnecessary, but for now we can use some Yoneda-style tricks to show this:

- Suppose $a \mid b$. We want to show $\frac{a}{\text{gcd}(a, k)} \mid \frac{b}{\text{gcd}(b, k)}$

- By Baby Yoneda, it suffices to show $\forall m \in \mathbb{N}, \frac{b}{\text{gcd}(b, k)} \mid m \implies \frac{a}{\text{gcd}(a, k)} \mid m$. This is what such a relationship would “do”, after all.

- Using the respective universal properties, we need to show $b \mid km \implies a \mid km$. But that’s true since $a \mid b$, by transitivity!

One cute application of this is providing a formula for the lowest common multiple of two numbers in terms of their gcd:

$\text{lcm}(a, b) = \frac{ab}{\text{gcd}(a, b)}$

As always, we show this by verifying the corresponding universal property:

- $\text{lcm}(a, b) \mid m \iff a \mid m \text{ and } b \mid m$

- And that’s $\iff a \mid b (\frac mb) \text{ and } b \mid m$. We’re allowed to use $\frac mb$ since we know $b$ divides $m$.

- Using the adjunction above, that’s $\iff \frac{a}{\text{gcd}(a, b)} \mid \frac mb \text{ and } b \mid m$

- Multiplying through by $b$, that’s $\iff \frac{ab}{\text{gcd}(a, b)} \mid m \text{ and } b \mid m$. But now the second proposition is redundant, since $b \mid \frac{ab}{\text{gcd}(a, b)}$, so transitivity already guarantees $b \mid m$.

- Thus, by Baby Yoneda, $\text{lcm}(a, b) = \frac{ab}{\text{gcd}(a, b)}$.

There’s also a cool application of this to group theory! For this, we’ll need the universal property of order:

Let $G$ be a group and $g \in G$. Then the order of $g$, $o(g)$, satisfies $o(g) \mid n \iff g^n = e$.

The fact we can prove with the above adjunction is then:

Let $G$ be a group, $g \in G$, and $k \in \mathbb{N}$. Then $o(g^k) = \frac{o(g)}{\text{gcd}(o(g), k)}$.

Proof - again, we use the universal property. $o(g^k) \mid n \iff (g^k)^n = e \iff g^{kn} = e \iff o(g) \mid kn \iff \frac{o(g)}{\text{gcd}(o(g), k)} \mid n$. The result then follows by Baby Yoneda.

Finally, we can show that multiplication by $k$ does not have a right adjoint, using the example of $k = 3$. Suppose there was some $h(n)$ such that $3m \mid n \iff m \mid h(n)$. Following the identity from right to left, we deduce $3 h(n) \mid n$, so that in particular $3 \mid n$. Thus, $h(n)$ can only be defined if $n$ is already a multiple of $3$, in which case we can use $h(n) = \frac n3$. But otherwise, it doesn’t exist!

Relators and the Parameter Theorem

In a few of the examples above, I seemed to cheat by not explicitly checking monotonicity of the adjoint map. There also appeared to be a few examples of parametrised adjoints, where by varying some parameter $p$ we got a whole family of adjunctions. Perhaps surprisingly, these results can be unified under what’s known as the Parameter Theorem - but, before getting to that, we need to take a short diversion into the world of relators.

As the name suggests, a “relator” is to ordinary monotone maps as relations are to ordinary set functions. We don’t specify a unique output for each input, but instead focus on the ways in which elements of one ordered set may be compared to another.

In fact, we’ve met something a little like this before - virtual objects! Back in Discovering Products of Ordered Sets, I explained how a virtual object over an ordered set $X$ may be viewed as a monotone map $X^\text{op} \to 2$, while a virtual object under $X$ can be viewed as a monotone map $X \to 2$. These have virtual relationships $x \prec v$ and $w \prec x$ respectively to elements $x \in X$, with the left side of the relationship getting an “op”. We also saw the canonical monotone map $X^\text{op} \times X \to 2$ sending $(a, b) \mapsto (a \leq b)$, evaluated as a truth value.

Generalising these examples, we make the following definition:

A relator between ordered sets $A$ and $X$ is a monotone map $R : A^\text{op} \times X \to 2$. We can view it as a “virtual comparator” $R(a, x) = a \prec x$ defined for each $a \in A, x \in X$.

Monotonicity ensures we get transitivity of these virtual relationships - $a’ \leq a \text{ and } a \prec x \implies a’ \prec x$, and $a \prec x \text{ and } x \leq x’ \implies a \prec x’$, where I’ve viewed the relator as a bi-monotone map.

A common way to obtain such relators is by starting with a monotone map $f : A \to X$. In that case, we can compare elements of $A$ to those of $X$ by defining $R(a, x) := f(a) \leq x$ to get a relator $R : A^\text{op} \times X \to 2$. And we can also define $S(x, a) := x \leq f(a)$ to get a relator $S : X^\text{op} \times A \to 2$. In this way, any monotone map naturally defines two relators.

Note that our previous examples of adjunctions all involved relators in the background. For example, there is a natural relator $R : \mathbb{Z}^\text{op} \times \mathbb{R} \to 2$ defined by $R(n, x) := n \leq x$. If we fix $x$, we get a virtual object $R(-, x) : \mathbb{Z}^\text{op} \to 2$ over $\mathbb{Z}$, represented by $\lfloor x \rfloor$. And if we fix $n$, we get a virtual object $R(n, -) : \mathbb{R} \to 2$ under $\mathbb{R}$, represented by $\iota(n)$, producing the adjunction $\iota(n) \leq x \iff R(n, x) \iff n \leq \lfloor x \rfloor$.

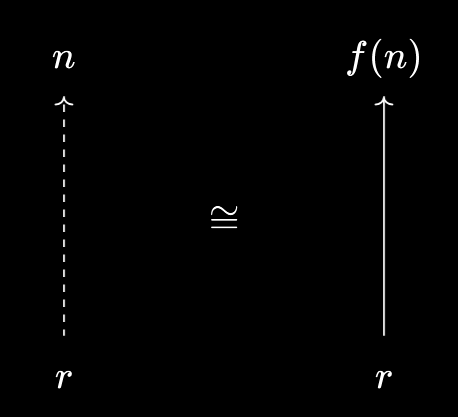

This appears to suggest adjunctions can be thought of as “bi-representable” relators; those relators $R(a, x)$ such that the corresponding virtual objects $R(a, -)$ under $X$ and $R(-, x)$ over $A$ are always representable, by $f(a)$ and $g(x)$ respectively. We then obtain an adjunction since $f(a) \leq x \iff R(a, x) \iff a \leq g(x)$, but with one caveat - we haven’t checked that $f$ and $g$ are monotone! However, as you may be beginning to suspect, this never needs to be checked explicitly. Indeed, this is the content of the Parameter Theorem:

(Parameter Theorem) Let $R : A^\text{op} \times X \to 2$ be a relator, and suppose for each fixed $x \in X$, the corresponding virtual object $R(-, x) : A^\text{op} \to 2$ is representable. By choosing representations $g(x)$ for each of these, we obtain a monotone map $g : X \to A$ with $R(a, x) \iff a \leq g(x)$.

In other words, a relator that is “pointwise representable” automatically defines a monotone map! I find the proof of this quite lovely:

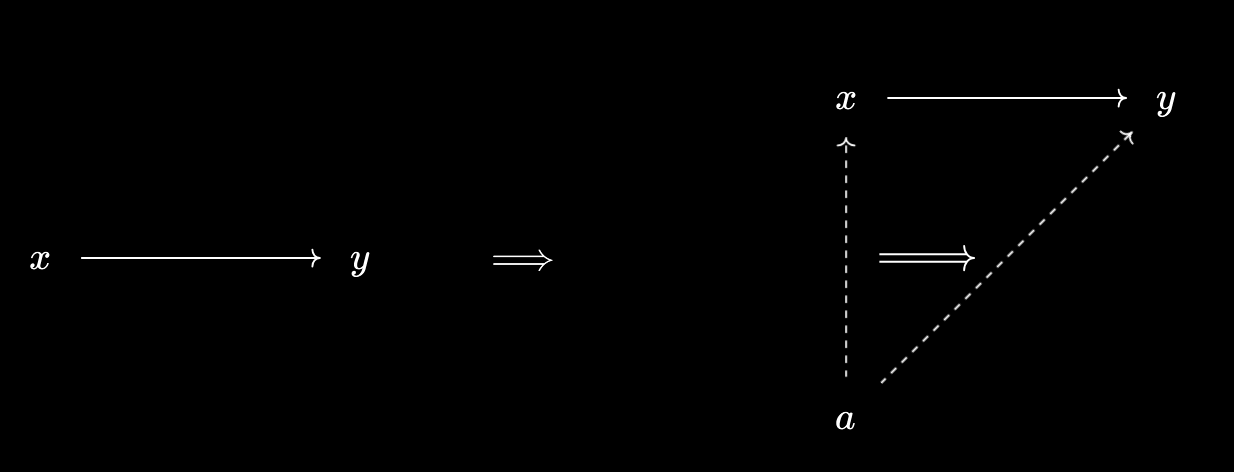

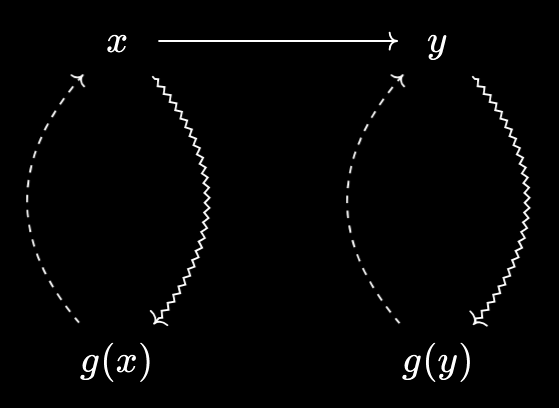

- Take two objects $x, y \in X$, where we know $x \leq y$.

- Using the relator, we know that what $x \leq y$ “does” is allow us to transform $a \prec x$ to $a \prec y$. In other words, $x \leq y \implies \forall a \in A, a \prec x \implies a \prec y$.

. Note that, unlike Baby Yoneda, this isn’t an equivalence, since we can’t just set $a = x$.

. Note that, unlike Baby Yoneda, this isn’t an equivalence, since we can’t just set $a = x$. - Now, by assumption, $x$ and $y$ as virtual objects over $A$ both have representations $g(x)$ and $g(y)$:

- But we can follow these arrows to conclude $g(x) \leq g(y)$! Or, if you prefer, we use Baby Yoneda - $\forall a \in A, a \leq g(x) \iff a \prec x \implies a \prec y \iff a \leq g(y)$, whence following the identity $g(x) \leq g(x)$ allows us to conclude $g(x) \leq g(y)$.

$R(a, x)$ being representable for each fixed $x \in X$ can be thought of as being “representable in the $A^\text{op}$ argument”. Here, I’m borrowing terminology from multilinear algebra - a multivariable function is linear in an argument when, with all other arguments fixed, the corresponding function is linear. Similarly here - $R : A^\text{op} \times X \to 2$ is representable in the first argument when, with $x \in X$ fixed, the corresponding virtual object $A^\text{op} \to 2$ is representable.

What if it’s representable in the $X$ argument? Viewing $A^\text{op} \times X$ as $(X^\text{op})^\text{op} \times A^\text{op}$, we obtain a monotone map $A^\text{op} \to X^\text{op}$, i.e. a monotone map $f : A \to X$ with $f(a) \leq x \iff R(a, x)$. This allows us to give an alternative “lightweight” definition of adjunction:

An adjunction between $A$ and $X$ consists of a relator $R : A^\text{op} \times X \to 2$ that is birepresentable, meaning representable in each argument.

This implies the existence of monotone maps $f : A \to X$ and $g : X \to A$ with $f(a) \leq x \iff R(a, x) \iff a \leq g(x)$. But monotonicity of $f$ and $g$ doesn’t need to be checked explicitly - it follows from the monotonicity intrinsic to $R$ together with the Baby Yoneda lemma.

Now we can interpret the “partial adjoints” we saw beforehand - given a relator $R : A^\text{op} \times X \to 2$, we can form a new relator $R’ : A^\text{op} \times X’ \to 2$ by restricting to the subset $X’ \subset X$ on which $R(-, x) : A^\text{op} \to 2$ is representable. This gives us a monotone map $X’ \to A$. So, even if we don’t get a globally-defined adjoint, we get about the next best thing - a monotone map defined on the “maximal domain” of representability.

We also get a nice way to talk about “parametrised adjunctions”, like we saw with $n \mid km \iff \frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, k)} \mid m$. In this case, we see that $n \mid km$ is a relator in 3 variables, $R : \mathbb{N}^\text{op} \times \mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N} \to 2$ defined by $R(n, k, m) := (n \mid km)$. To prove this, we need only check it is “separately monotone” in each variable:

- $n’ \mid n\text{ and } n \mid km \implies n’ \mid km$, so we do have $n’ \mid n \text{ and } R(n, k, m) \implies R(n’, k, m)$

- $k \mid k’ \text{ and } n \mid km \implies n \mid k’ m$ since we get $km \mid k’ m$. So we do have $k \mid k’ \text{ and } R(n, k, m) \implies R(n, k’, m)$.

- $m \mid m’ \text{ and } n \mid km \implies n \mid k m’$ for the same reason, so it is also monotone in this argument.

In our case, the $k$ value was a “parameter” that we used to get a family of adjunctions. As expected, $R$ is representable in the first and third arguments:

- For each fixed $(k, m)$ the map $n \mapsto R(n, k, m) = (n \mid km)$ is representable by… $km$ itself!

- For each fixed $(n, k)$ the map $m \mapsto R(n, k, m) = (n \mid km)$ is representable by $\frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, k)}$, since $\frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, k)} \mid m \iff n \mid km$

So, we can view a “parametrised” adjunction as a relator $R : P \times A^\text{op} \times X \to 2$ that is representable in its second and third arguments. By the parameter theorem, these automatically give monotone maps $f : P \times X \to A$ and $g : P \times A^\text{op} \to X^\text{op}$ with $R(p, x, a) \iff a \leq f(p, x) \iff g(p, a) \leq x$.

In fact, the example $n \mid km$ is a little stronger than a two-variable adjunction, since it is also representable in the $k$ argument!

- For each fixed $(n, m)$, the map $k \mapsto R(n, k, m) = (n \mid km)$ is representable by $\frac{n}{\text{gcd}(n, m)}$.

This is an example of what’s known in the business as a two-variable adjunction - a relator in three variables that is representable in each variable separately. Of course, you can generalise to relators in many variables representable in some or all of your arguments - the parameter theorem ensures that checking “pointwise” representability is enough to get monotonicity.

An Intermission

This article is getting quite long, so I’ll split it off into another part. While I went into detail with a few adjunctions today, next time I’ll try to cover:

- A lot more examples of them.

- Right adjoints preserve meets, left adjoints preserve joins.

- The Adjoint Functor Theorem, for ordered sets.

- Contravariant adjunctions, including the OG Galois connection of Galois theory!

- Why call these adjoints? The relation to the concept in Linear Algebra.

Looking back on that list, it’s a wonder I ever thought this would fit in a single article. Perhaps I need to get a little better at splitting these up… Anyway, stay tuned!