Discovering Products of Ordered Sets

Packaging Monotone Maps

Before releasing the next article in the “Baby Yoneda” series, I want to do another exploration in a similar style to Discovering Topological Products, but this time for products of ordered sets. Unlike the product topology, defining the product of two ordered sets $A$ and $B$ is quite straightforward - it’s essentially just defined componentwise - but I think it’s still a useful exercise to see how we can derive it purely from the universal property!

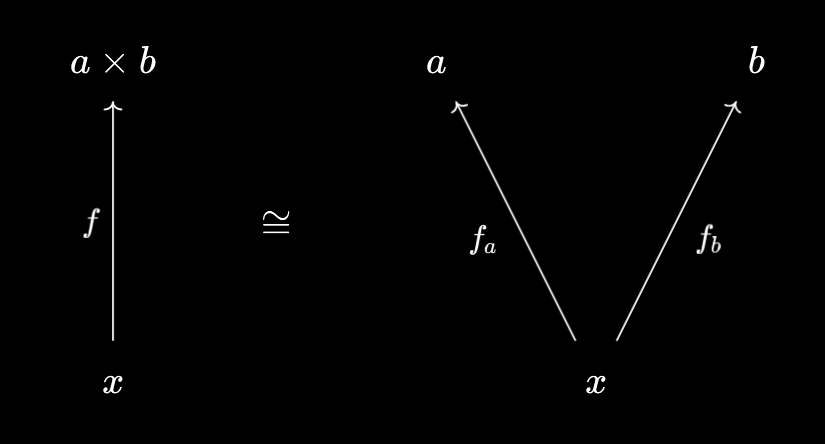

So, what should the categorical product of two ordered sets $A$ and $B$ be? Recalling Products, Categorically, we know that the role of a product $A \times^\text{cat} B$ is to allow you to package and unpackage pairs of morphisms $Z \to A, Z \to B$:

However, we haven’t yet defined what a “morphism between ordered sets” should be! The most common choice is to choose maps that respect the ordering on input and output sets. Formally, we make the following definition:

Let $(A, \leq_A)$ and $(B, \leq_B)$ be two ordered sets. A monotone map \(f : (A, \leq_A) \to (B, \leq_B)\) is a function $f : A \to B$ such that $a \leq_A a’ \implies f(a) \leq_B f(a’)$.

Often we abuse notation and just write $a \leq a’ \implies f(a) \leq f(a’)$. Thus, the goal of our categorical product will be to compress two monotone maps into a single one.

First, we should probably see some examples of monotone maps to get some intuition. Luckily, we’ve secretly been working with them for quite a few articles now - virtual objects! Specifically, let $2$ denote the ordered set \(\{0, 1\}\) with $0 \leq 1$ (together with reflexivity). Then:

- A virtual object $v$ over an ordered set $X$ is a monotone map $X^\text{op} \to 2$, where $X^\text{op}$ is the ordered set obtained from $X$ by reversing the order.

- A virtual object $w$ under an ordered set $X$ is a monotone map $X \to 2$.

Indeed, these monotone maps are precisely the “virtual comparison predicates” $x \prec v$ and $w \prec x$ respectively - monotonicity is precisely what we need to ensure $(y \leq x \text{ and } x \prec v) \implies y \prec v$, which in predicate-land becomes $y \leq x \implies p(x) \leq p(y)$. Note the reversal of the order, which is why we needed to introduce the opposite ordering, with $x \leq^\text{op} y \iff y \leq x$.

Probing the Product

Elements

Much like the case of topological products, we can exploit the universal property by using specially-chosen ordered sets $Z$. For example, in the topological space, we used the one-point space $*$ to deduce that the categorical product $X \times^\text{cat} Y$ had underlying set $X \times^\text{set} Y$.

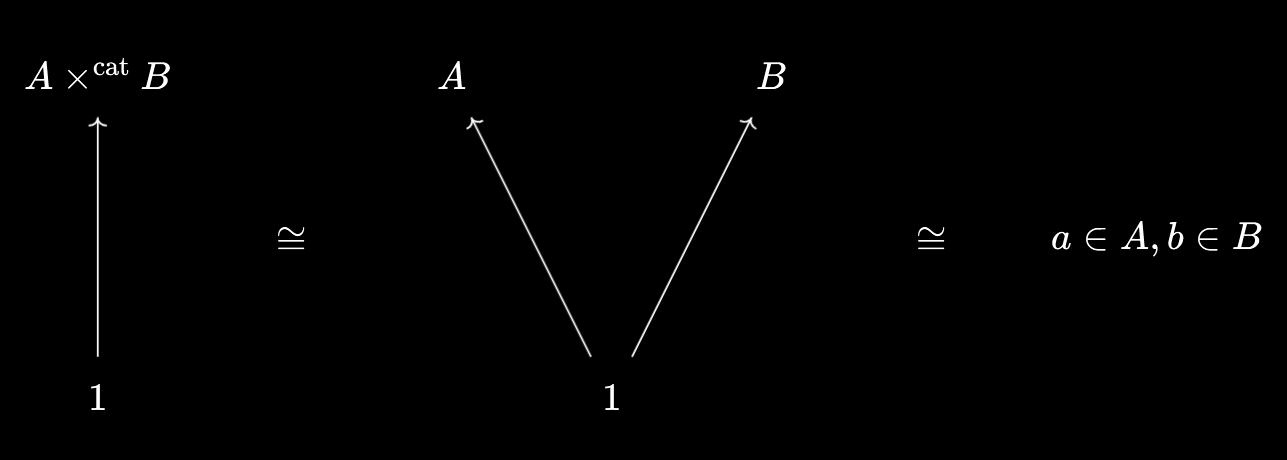

We can do something very similar here! Let $1$ denote the ordered set \(\{0\}\) with $0 \leq 0$ required by reflexivity. Then we have that:

If $X$ is an ordered set, then monotone maps $1 \to X$ correspond precisely to elements of $X$.

Indeed, a monotone map $f : 1 \to X$ sends $0 \mapsto f(0) \in X$, giving us an element of $X$. But moreover, any $x \in X$ defines a monotone map $0 \mapsto x$, since monotonicity only requires $0 \leq 0 \implies x \leq x$, which is true by reflexivity.

I like to think of this as encapsulating the “shape” of a set element in a particular ordered set, $1$, so that maps out of this set pick out “$1$-shaped elements”.

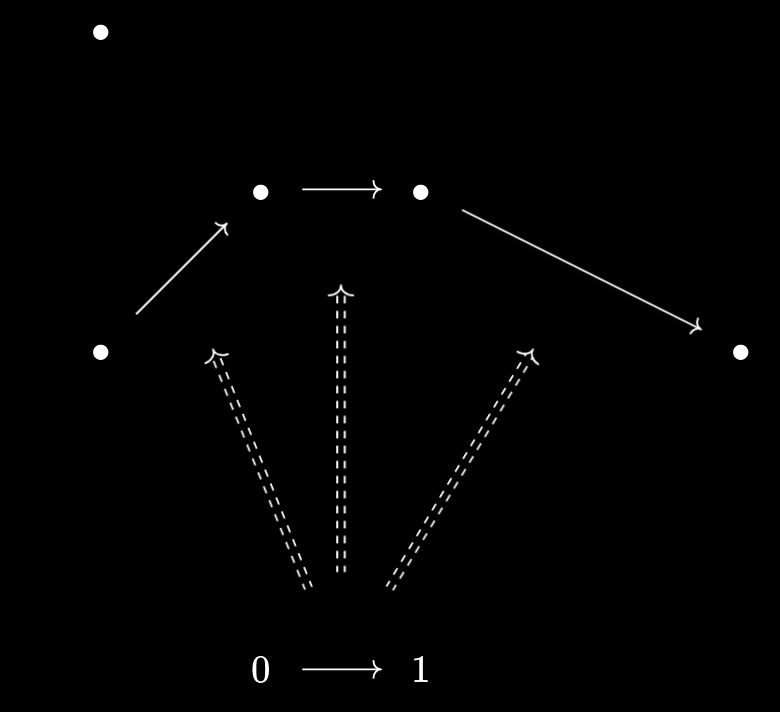

Here, the dashed arrows denote ways to map our unique element $0$ into $X$, corresponding precisely to elements of $X$. Elements are point-like, so it makes sense that the “shape” which picks them out is also point-like.

So, say we have two ordered sets $A$ and $B$. Then the elements of $A \times^\text{cat} B$ correspond to monotone maps $1 \to A \times^\text{cat} B$. But by the universal property, these correspond to pairs of monotone maps $1 \to A, 1 \to B$, i.e. pairs of elements $a \in A, b \in B$!

So, we’ll choose the set $A \times B$ for the categorical product $A \times^\text{cat} B$. All that remains is to determine the ordering…

Ordering

We saw in the last section that the universal property allowed us to find “$1$-shaped elements of $A \times^\text{cat} B$” in terms of “pairs of $1$-shaped elements of $A$ and $B$”. This was helpful because “$1$-shaped elements” of an ordered set correspond precisely to ordinary elements.

If we allow our notion of “shape” to wander, then we can interpret the universal property as saying “$Z$-shaped elements of $A \times^\text{cat} B$” correspond to “pairs of $Z$-shaped elements of $A$ and $B$”, where a $Z$-shaped element of an ordered set $A$ is just a monotone map $f : Z \to A$.

So, if we want to determine what the order on $A \times^\text{cat} B$ is, we can try to search for some ordered set $Z$ such that “$Z$-shaped elements” help determine the order. In fact, we’ve already met such an ordered set - $2$! Namely:

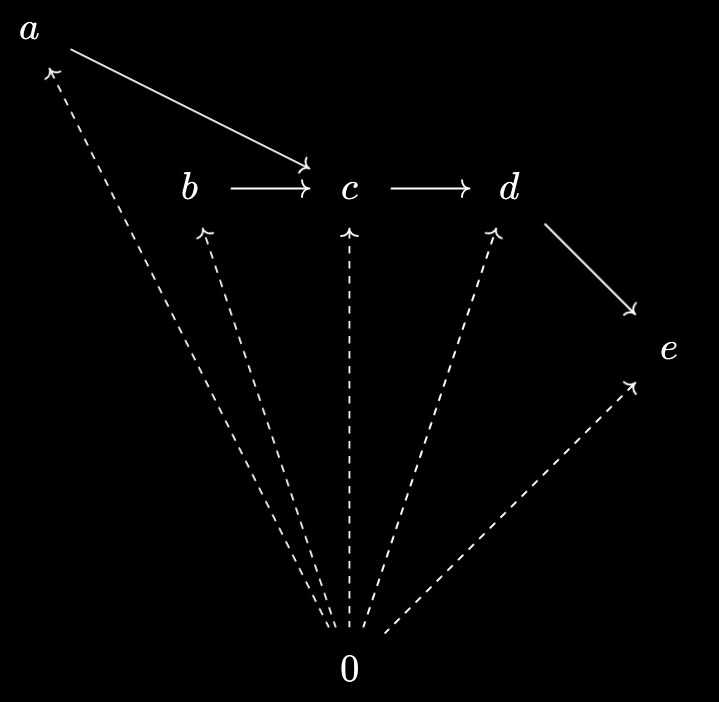

If $X$ is an ordered set, then the $2$-shaped elements of $X$ correspond precisely to pairs $x_0, x_1 \in X$ with $x_0 \leq x_1$.

I’ll leave this proof as an exercise for the reader - it’s good practice! I like to visualise this as encapsulating the shape of a “relationship” into an ordered set $2$:

Here, the dashed arrows denote ways to map our ordered set $2$ into $X$, corresponding precisely to the relationships present within $X$. Relationships are line-like and directed, so it makes sense that the “shape” which picks them out is a directed line segment.

Thus, relationships in $A \times^\text{cat} B$ correspond to monotone maps $2 \to A \times^\text{cat} B$. By the universal property, these unpackage to pairs of monotone maps $2 \to A, 2 \to B$, i.e. pairs of relationships $a_0 \leq a_1, b_0 \leq b_1$.

Finally, this gives us the order on $A \times^\text{cat} B$ - we define $(a_0, b_0) \leq (a_1, b_1)$ to mean $a_0 \leq a_1 \text{ and } b_0 \leq b_1$.

Verifying the Product

Of course, all we’ve done so far is show that if the categorical product $A \times^\text{cat} B$ exists, it must be given by $A \times B$ with componentwise ordering. Now, we should check whether this really does satisfy the universal property - can we unpackage maps $Z \to A \times B$ to pairs of maps $Z \to A, Z \to B$ and vice-versa?

For unpackaging, we can use the universal projections $\pi_A : A \times B \to A, \pi_B : A \times B \to B$, which are the same as the set-theoretic ones. You can verify that these are indeed monotone maps. So, given a $f : Z \to A \times B$, we obtain $\pi_A \circ f : Z \to A$ and $\pi_B \circ f : Z \to B$.

How about packaging? Take a pair of monotone maps $g : Z \to A$ and $h : Z \to B$. We want to define $(g, h) : Z \to A \times B$ by $(g, h)(z) = (g(z), h(z))$. All we need to check is that $(g, h)$ is monotone, and we’ll be done!

But if $z \leq z’$, then $g(z) \leq g(z’)$ and $h(z) \leq h(z’)$ by monotonicity of $g$ and $h$. Then, by the definition of $A \times B$, we have $(g(z), h(z)) \leq (g(z’), h(z’))$. Thus, $(g, h)(z) \leq (g, h)(z’)$, as required.

Bi-monotone maps

We’ve successfully found the categorical product of two ordered sets $A$ and $B$, and the universal property that determines maps into $A \times B$. Before we finish for today, I want to explore what maps out of $A \times B$ look like - given an ordered set $Z$, how do we define a monotone map $f : A \times B \to Z$?

The universal property won’t help us here, so we’ll have to dig into the details of the construction for $A \times B$. All we need is that, if $a \leq a’$ and $b \leq b’$, then $f(a, b) \leq f(a’, b’)$ in $Z$. Seems easy enough, but there’s more to see here.

Note that, by reflexivity, we have that $a \leq a’ \implies f(a, b) \leq f(a’, b)$, since we can use $b \leq b$. Similarly, we can also get $b \leq b’ \implies f(a, b) \leq f(a, b’)$. Much like bilinear maps, it appears that $f$ is “monotone in each argument” - if we fix one of the arguments, we get a monotone map in the other arugment.

This leads to the following definition:

Let $A, B$ be ordered sets. A bi-monotone map is a function $f : A \times B \to Z$ such that, for each fixed $a \in A$, $f(a, -) : B \to Z$ is a monotone map, and for each fixed $b \in B$, $f(-, b) : A \to Z$ is a monotone map.

We’ve already seen that a monotone map $A \times B \to Z$ is necessarily bi-monotone. But it turns out the converse is true too:

- Suppose $f : A \times B \to Z$ is bi-monotone. Suppose $a \leq a’$ and $b \leq b’$, we want to show $f(a, b) \leq f(a’, b’)$

- Well, since $a \leq a’$, fixing $b$ we get that $f(a, b) \leq f(a’, b)$.

- Then, fixing $a’$ and using $b \leq b’$, we get that $f(a’, b) \leq f(a’, b’)$.

- So, by transitivity, we can conclude that $f(a, b) \leq f(a’, b’)$.

So why the distinction? While these definitions are logically equivalent, it’s often easier to check in practice that a map is bi-monotone rather than monotone. You only need to keep track of monotonicity in one variable at a time, rather than all-at-once.

Indeed, this generalises seamlessly to products of many ordered sets. We can define the notion of an $n$-monotone map $A_1 \times \dots \times A_n \to Z$ that is separately monotone in each factor, and deduce a similar equivalence between $n$-monotone maps and ordinary monotone maps. This lets us decompose checking monotonicity into $n$ easier problems.

As an example, for any ordered set $X$ we get a canonical monotone map \(\text{Rel} : X^\text{op} \times X \to 2\) defined by \(\text{Rel}(a, b) := (a \leq b)\), viewed as a truth value. Checking it is bi-monotone amounts to the following:

- If $b \leq c$ then $\text{Rel}(a, b) \implies \text{Rel}(a, c)$. But this just says $a \leq b \text{ and } b \leq c \implies a \leq c$

- if $d \leq a$ then $\text{Rel}(a, b) \implies \text{Rel}(d, b)$. But this just says $d \leq a \text{ and } a \leq b \implies d \leq b$.

This will play a crucial role in the next article of the “Baby Yoneda” series, on adjunctions.

Closing Thoughts

In more general categories, the concept of using objects as “shapes” to probe other objects using morphisms is known as Lawvere’s Philosophy of Generalised Elements. A $Z$-shaped element of an object $A$ is just a morphism $Z \to A$. This technique can help turn category-theoretic proofs into ones that look essentially set-theoretic, by sticking the word “generalised” in front of all your elements and being careful to ensure you only make legal manipulations with these elements.

The notion of bi-monotone maps generalises to bifunctors, which are functors whose domain is a product category. In that case, a result called the bifunctor lemma allows you to reduce checking functoriality to “separate functoriality”, plus an interchange condition. This is at the heart of naturality, a big motivation for why the subject of category theory was invented in the first place!