Discovering Topological Products

A Pointwise Puzzle

Here’s a question from my undergrad which was much harder than I anticipated at the time:

Let $X$ be a topological space, and $f, g : X \to \mathbb{R}$ be continuous functions. Show that $h(x) = f(x) \times g(x)$, their pointwise product, is continuous.

If I was in the setting of metric spaces, this would’ve been straightforward; metric continuity is equivalent to sequential continuity, so it’s enough to check that $x_n \to x \implies h(x_n) \to h(x)$. But since $f, g$ are continuous, we know that $x_n \to x \implies f(x_n) \to f(x) \land g(x_n) \to g(x)$, whence we can use “limit of product is product of limits” to conclude $f(x_n) g(x_n) \to f(x) g(x)$, as required. In fact, this proof can be adapted to work for the general topological case using nets, but I was wholly unaware of those at the time.

The only thing I could think of, then, was to check continuity “manually”. Take an open set $U \subset \mathbb{R}$, try to compute $h^{-1}(U)$, and show this is open in $X$ using continuity of $f$ and $g$. It’s… doable, but not especially pleasant.

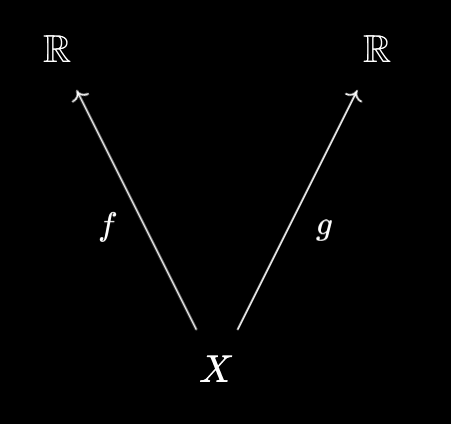

Using ideas from our recent article on Products, Categorically, however, we can solve this question more easily. We visualise the pair of functions $f, g$ diagramatically:

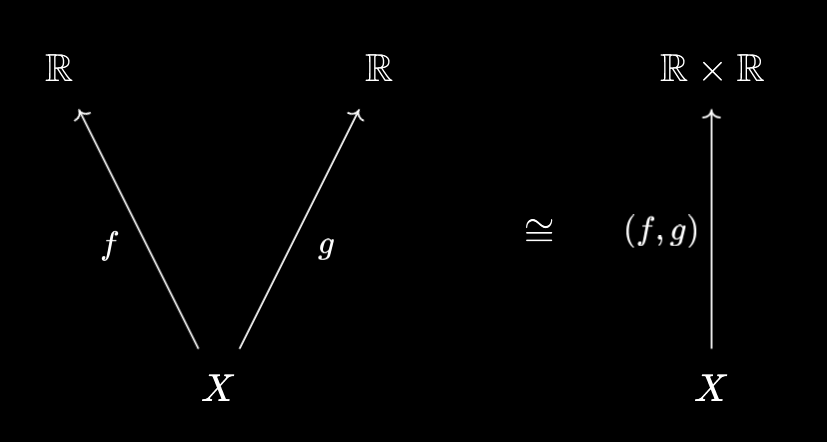

Then, viewing the product as a packager, we can compress these into a single continuous function:

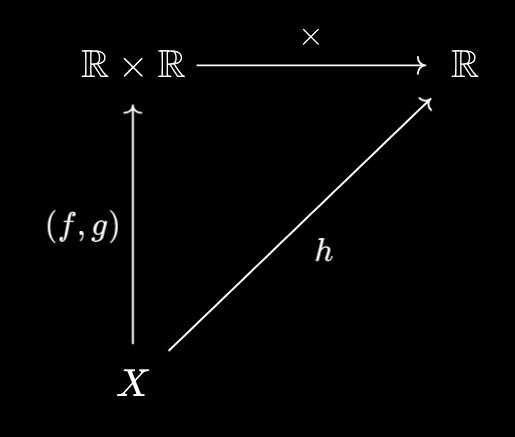

Then, we can construct $h = (\times) \circ (f, g)$, where $\times : \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ is just multiplication viewed as a binary operation:

Since we already know the packaged $(f, g)$ is continuous, it suffices to show that $\times : \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ is continuous. But now the domain and codomain are metric spaces, so we can just use the metric space sequential characterisation of continuity!

This was the solution presented by my supervisor, though not expressed as explicitly in categorical language, and it left quite an impression on me. It seemed really elegant, and the kind you could definitely come up with yourself so long as you knew this “packaging” property of products!

On that note, why does the product topology allow you to package continuous maps, anyway? This is the subject of today’s article - starting just from the universal property, we’ll derive the definition of the product topology, both for finite and infnite collections!

A Sanity Check

Before proceeding, we should check that the categorical product of two topological spaces $X$ and $Y$ really will involve putting a topology on their cartesian product as sets, $X \times^\text{set} Y$. Most examples of products do take this form, but it’s illuminating to see how we can derive this purely from the universal property.

The key observation is that, just using continuous maps, we can recover the underlying set of a topological space! There is a unique topology on any one-point space \(*\), and it’s such that any map $* \to A$ is continuous, for $A$ any topological space. Such a map is entirely determined by the image of the single point, which is some element $a \in A$. The upshot is that elements of $A$ naturally correspond to continuous maps $* \to A$.

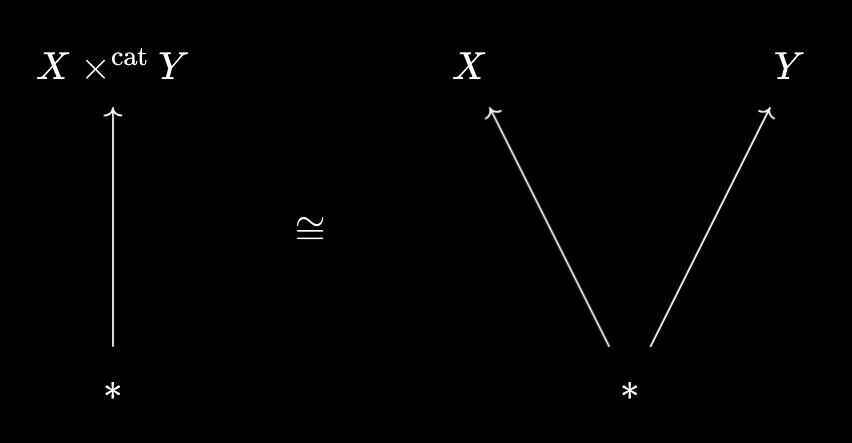

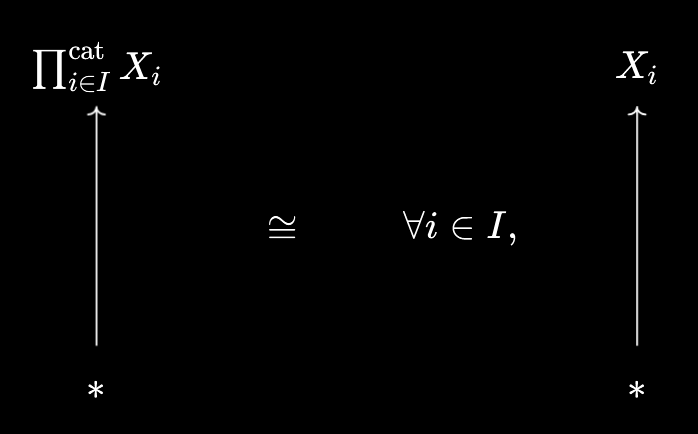

So, what will elements of the categorical product $X \times^\text{cat} Y$ correspond to? Using the above observation, they’ll be continuous maps $* \to X \times^\text{cat} Y$. But now we can use the universal property to “unpackage” this map:

So, these correspond to pairs of continuous maps $* \to X, * \to Y$, i.e. to pairs $(x, y) \in X \times^\text{set} Y$! Thus, even if we don’t know everything about the topological space $X \times^\text{cat} Y$ yet, we’ve managed to deduce that its underlying set should be $X \times^\text{set} Y$, via probing it with the one-point space $*$.

An entirely analogous argument shows that, for an arbitrary collection of topological spaces \((X_i)_{i \in I}\), the underlying set of the categorical product $\prod_{i \in I}^\text{cat} X_i$ should be $\prod_{i \in I}^\text{set} X_i$:

The Universal Projections

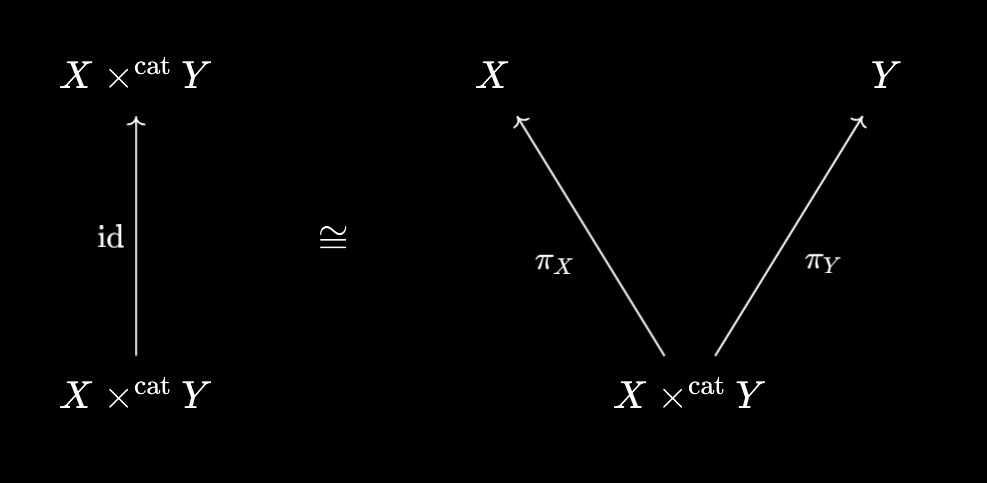

As we’ve seen in Products, Categorically, it’s helpful to consider the result of “unpackaging” the identity map. Doing this gives us the universal projections for the product:

Since we’re taking the underlying set of $X \times^\text{cat} Y$ to be the cartesian product as sets, we can take these projections to be the set-theoretic projections. This also lines up with what we want the categorical product to “do” - given a function $f : Z \to X \times^\text{cat} Y$, we want to write it as $f(z) = (g(z), h(z))$ and unpackage to $g : Z \to X, h : Z \to Y$. For this we need $g = \pi_X \circ f, h = \pi_Y \circ f$, which forces the familiar projection functions.

So, whatever topology we have on $X \times^\text{set} Y$, it must be so that these projections are indeed continuous maps. But there are lots of topologies that would make this work - at the extreme end, the discrete topology! How do we pick out the correct one, $\sigma$, for the categorical product?

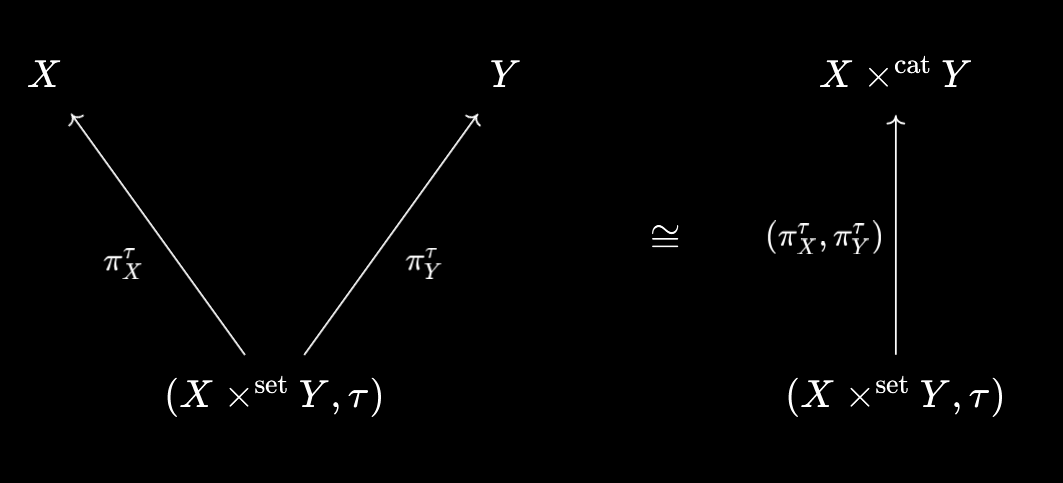

If you play around with the problem a little, you might make the following observation. Suppose $\tau$ is a topology on $X \times^\text{set} Y$ that makes the set-theoretic projections continuous - we denote the associated topological space $(X \times^\text{set} Y, \tau)$. Then we should be able to “package” these projections together:

Now, set-theoretically, this map is just the identity $X \times^\text{set} Y \to X \times^\text{set} Y$ - the universal property guarantees this is a continuous map from $(X \times^\text{set} Y, \tau)$ to $X \times^\text{cat} Y$.

If we apply the preimage definition of continuity, then this says that, if $U \subset X \times^\text{set} Y$ is open in $X \times^\text{cat} Y$, then $\text{id}^{-1}(U)$ is open in $(X \times^\text{set} Y, \tau)$. In more elementary terms, any subset which is open in the categorical product topology must necessarily be open in $\tau$, so that $\sigma \subset \tau$. Thus, the categorical product topology is coarser than any topology on $X \times^\text{set} Y$ making the projections continuous, containing the minimal number of open sets to ensure this holds.

Building the topology

From this point, the argument shifts from a categorical to a topological flavour - still, for completeness, I’ll include it. In order for the projection $\pi_X$ to be continuous, we need $\pi_X^{-1}(U) \subset X \times Y$ to be open for any $U \subset X$ open.

But we can compute $\pi_X^{-1}(U)$ explicitly - it’s just $U \times Y$. So, we know that sets of the form $U \times Y$ will be open in our categorical product topology. Similarly, sets of the form $X \times V$ will be open, for $V \subset Y$ open.

Can we take just those sets? In general, no - for example, the intersection of $U \times Y$ and $X \times V$ must be open, but is also $U \times V$, which isn’t included in our collection if both $U$ and $V$ are nonempty proper subsets.

However, this is easily fixed - we just take the topology generated by the open sets we’ve been “forced” to include in $X \times Y$! This will consist of arbitrary unions of finite intersections of our “basic” open sets, which you can verify satisfy the axioms of a topology. Explicitly, these turn out to be arbitrary unions of sets of the form $U \times V$ for $U \subset X, V \subset Y$ open.

How about the infinitary version? In order for the projection $\pi_{X_i}$ to be continuous, we need $\pi_{X_i}^{-1}(U) \subset \prod_{j \in I} X_j$ to be open for any $U \subset X_i$ open.

And again, we can compute that preimage explicitly - it is $\prod_{j \in I} Y_j$ where \(Y_j = \begin{cases} U \text{ if } j = i \\ X_i \text{ otherwise } \end{cases}\). These are precisely the open sets we’re “forced” to include in our topology to ensure the projections are continuous.

Then, taking the topology generated by these gives the product topology on $\prod_{i \in I} X_i$ - arbitrary unions of finite intersections of “basic” open sets. The finiteness is important, since a finite intersection of our basic opens is a subset of the form $\prod_{j \in I} Z_j$ where only finitely many $Z_j$ are not equal to $X_j$ (with the other factors being open subsets).

Thus, the product topology on an infinitary product consists of arbitary unions of these subsets, which reproduces the familiar definition. Note that the “box” topology, which consists of unions of any subset $\prod_{j \in I} U_j$, is (in general) strictly finer, and so won’t satisfy the universal property.

Checking the universal property

So far we’ve only shown that if there is a categorical product topology, it must take the form of the usual product topology. But does this actually work as a categorical product?

Since it’s been constructed to have the projections continuous, we know that “unpackaging” is guaranteed to work. Thus, it suffices to check that “packaging” works. So, take a family of continuous maps $f_i : Z \to X_i$, and package these (set-theoretically) into a map $f : Z \to \prod_{i \in I} X_i$. We just need to check that $f$ is actually continuous.

So, we take an open subset $U \subset \prod_{i \in I} X_i$, and check that $f^{-1}(U)$ is open. But since preimages preserve unions, it suffices to check this only for finite intersections of our “basic” opens.

Moreover, preimages preserve intersections, and a finite intersection of open subsets of $Z$ is open. So in fact, it suffices to check this for our “basic” opens, i.e. $\prod_{j \in J} Y_j$ where \(Y_j = \begin{cases} V \text{ if } j = i \\ X_i \text{ otherwise } \end{cases}\), with $V \subset X_j$ open.

Then, $f^{-1}(Y_j)$ can be computed to be $f_i^{-1}(V)$. But we know this is open, since $f_i : Z \to X_i$ is continuous! Thus, $f$ is continuous, and “packaging” works with this definition of the product topology, as required.

Bases for topologies

The last section is actually an instance of a more general principle (what do you expect from a category theory article??). Suppose $(X, \tau)$ is a topological space, and that a family of open subsets $\mathcal{B}$ of $X$ is a sub-basis for this topology - meaning that every open subset of $X$ may be written as a union of a finite intersection of elements of $\mathcal{B}$. Or equivalently, that $\tau$ is precisely the topology generated by the family $\mathcal{B}$.

Then, to check continuity of maps into $X$, it suffices to check that the preimage of any $B \in \mathcal{B}$ under your map is open. The preimage of an arbitrary open set will then be a union of a finite intersection of known open sets, thus open. So, bases give you a nice way to check continuity of maps into a topological space!