Subset Images, Categorically

Intersecting Problems

In my recent article on Why Preimages Preserve Subset Operations, I explained that taking preimages of subsets can be viewed simply as function composition with predicates. The preservation of operations like intersection, union, complement, symmetric difference follows simply from the fact that precomposition commutes with postcomposition, i.e. associativity.

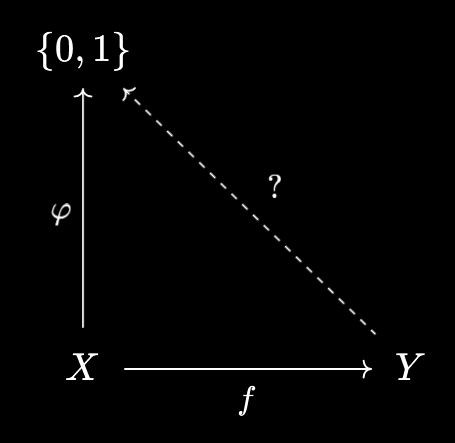

But what about direct images, which, given a function $f : X \to Y$, map subsets of $X$ to subsets of $Y$? These don’t have as nice an interpretation on predicates. If we have \(\varphi : X \to \{0, 1\}\), the direct image operation is supposed to produce a new predicate \(\psi : Y \to \{0, 1\}\):

The arrows just don’t match up! So, in predicate-world, direct image is far less of a “natural” operation.

This is also reflected in how direct image interacts with subset operations. It’s always true that $f(A \cap B) \subseteq f(A) \cap f(B)$, but the reverse implication generally does not hold. For a counterexample, take $f$ to be a constant map, and $A, B$ to be nonempty disjoint subsets. Then $f(A \cap B) = f(\emptyset) = \emptyset$, while $f(A) \cap f(B)$ is a singleton. Direct image does preserve unions though, in that $f(A \cup B) = f(A) \cup f(B)$.

The goal of today’s article is to try and organise these facts under a single framework, to get a better idea of why they’re true. Along the way, we’ll meet generalised “exists” and “forall” quantifiers, discover set-theoretic “interior” and “closure” operators, and get a taste of adjoint functors. To start, we need to take a step back and ask not what the direct image is, but what it does.

The Universal Property

By what it “does”, I mean the following. Suppose you have a function $f : X \to Y$, and a subset $A \subset X$. What we want to understand is how $f(A) \subset Y$ relates to and interacts with other subsets of $Y$. Since these are subsets, the natural way to relate this is inclusion. Thus, given a subset $B \subset Y$, we can investigate whether there’s some characterisation of when $f(A) \subset B$ or $B \subset f(A)$.

If we think about the former, we might notice the following. In order for $f(A) \subset B$ to be true, we need to ensure that the image of any $a \in A$ lies in $B$. In symbols, we want $a \in A \implies f(a) \in B$. But we know an equivalent way to phrase $f(a) \in B$ - by definition, it’s $a \in f^{-1}(B)$.

So, if $f(A) \subset B$, then we know that $\forall a \in A, a \in f^{-1}(B)$. In fact, this is sufficient to deduce that $f(A) \subset B$. Given any $y \in f(A)$, we know $y = f(a)$ for some $a \in A$. And since we know $f(a) \in B$ always, we necessarily have $y \in B$.

This gives us a characterisation of when $f(A) \subset B$. It’s precisely when $\forall a \in A, a \in f^{-1}(B)$. Said differently, we have the following universal property:

$A \subset f^{-1}(B) \iff f(A) \subset B$

As promised, this tells us the way in which $f(A)$ relates to a generic subset $B \subset Y$. Namely, it’s exactly the same as the way in which $A$ relates to the preimage $f^{-1}(B)$, at least from the perspective of subset inclusion.

You can think of this as saying direct image is a “pseudo-inverse” to preimage. To be an actual inverse, we’d want $f(f^{-1}(B)) = B$ and $f^{-1}(f(A)) = A$, but these are not generally true. An alternative way to write these is saying $f(A) = B \iff A = f^{-1}(B)$. Thus, we see that the universal property is a kind of “weakening” of the requirements for a true inverse, where we replace $=$ by $\subset$.

Interior and Closure operators

As you may be familiar with from Products, Categorically, once you have a universal property it’s often helpful to try “following the identity”. Doing this for products allowed us to obtain the universal projections, via unpackaging the identity map.

Say we start with $f^{-1}(B) \subset f^{-1}(B)$, which is always true. Then the universal property lets us deduce $f(f^{-1}(B)) \subset B$. We can think of $f(f^{-1}(B))$ as a set-theoretic interior of $B$. Explicitly, it consists of all $y \in Y$ such that there exists some $x \in f^{-1}(B)$ with $f(x) = y$. Obviously we need $y \in B$ for this to be possible, but we also need $y \in \text{Im}(f)$, the image of $f$. And in fact this is sufficient - if $y \in B \cap \text{Im}(f)$, then there’s some $x \in X$ with $f(x) = y \in B$, meaning necessarily $x \in f^{-1}(B)$.

Thus, the “interior” of a subset $B \subset Y$ is $f(f^{-1}(B)) = B \cap \text{Im}(f)$. It consists only of those elements of $B$ that are accessible by applying $f$. Note that, much like the topological interior operation, this is idempotent - $(B \cap \text{Im}(f)) \cap \text{Im}(f) = B \cap \text{Im}(f)$.

In this case, a subset $B$ equals its interior if and only if $B \subset \text{Im}(f)$. This identity holds for all subsets of $Y$ if and only if $f$ is surjective, therefore. So, surjective functions are precisely those for which $f(f^{-1}(B)) = B \forall B \subset Y$, so that the direct image is a left inverse to preimage.

What about the other direction? We can start with $f(A) \subset f(A)$, which is always true. Then the universal property lets us deduce $A \subset f^{-1}(f(A))$. By analogy, we can think of $f^{-1}(f(A))$ as a set-theoretic closure of $A$. In fact, we’ve secretly seen this before in Three Perspectives on Equivalence Relations!

Explicitly, $f^{-1}(f(A))$ consists of all $x \in X$ such that $f(x) \in f(A)$, i.e. such that there exists some $a \in A$ with $f(x) = f(a)$. What we’ve done is taken the kernel pair of $f$, meaning the equivalence relation $\sim$ defined by $x \sim x’ \iff f(x) = f(x’)$, and then taken the closure of $A$ under this equivalence relation. We simply throw in all $x \in X$ that are related to some element of $A$. Thus, we can also view $f^{-1}(f(A)) = \bigcup_{a \in A} [a]$, where $[a]$ is the equivalence class corresponding to $a \in A$.

In this case, a subset $A$ equals its closure if and only if it’s already a union of such equivalence classes. By considering singletons, this identity holds for all subsets of $X$ only if $f$ is injective, since we need the closure of a singleton to be a singleton. But this is actually sufficient - if $f$ is injective, then $f(x) = f(a) \implies x = a$, so $f(x) \in f(A)$ already implies $x \in A$, meaning $f^{-1}(f(A)) = A$. So, injective functions are precisely those for which $f^{-1}(f(A)) = A \forall A \subset X$, so that the direct image is a right inverse to preimage.

Of course, if $f$ is bijective, then direct image is a two-sided inverse to preimage. In this case, taking the preimage along $f$ is identical to taking the direct image along $f^{-1}$, so that the notation $f^{-1}(B)$ has a consistent interpretation, thankfully.

The Correspondence Theorem

As an application of these ideas, I’d like to illustrate a theorem which gave me a little trouble in undergrad - the correspondence theorem for normal subgroups:

Let $G$ be a group, and $N$ be a normal subgroup. Then subgroups of $G / N$ naturally correspond to subgroups of $G$ containing $N$.

Conceptually, the theorem is pretty cool; it says that the lattice of subgroups of $G / N$ can be identified with the lattice of subgroups “above $N$” in $G$. My main issue at the time was that the proof seemed to be, for lack of a better word, “symbol soup”. I was never fully confident I could reproduce it from scratch.

Let’s see if the work we’ve done so far can help. There’s a canonical projection homomorphism $\pi : G \to G/N$ sending $g \mapsto gN$, and the idea is to use this to set up the correspondence. Specifically:

- Given a subgroup $H \leq G$, $\pi(H)$ is a subgroup of $G / N$, since the image of a subgroup under a homomorphism is a subgroup.

- Given a subgroup $K \leq G / N$, the preimage $\pi^{-1}(K)$ is a subgroup of $G$. This is a general fact - the preimage of a subgroup under a homomorphism is a subgroup. For example, the preimage of the trivial subgroup is precisely the kernel of your homomorphism!

Now we need to investigate which subgroups this produces a bijective correspondence between - we’ll need the subgroups of $G$ to be equal to their closures, and the subgroups of $G/N$ to be equal to their interiors.

However, $\pi$ is surjective, being a quotient map. So the “interior” of any subset of $G / N$ is equal to that subset! That means every subgroup of $G/N$ is part of our correspondence, as expected.

How about taking the closure? The equivalence relation on $G$ we get is $g \sim g’ \iff \pi(g) = \pi(g’)$, which is $\iff g N = g’ N$, which is $\iff g^{-1} g’ \in N$. So, if we start with a subgroup $K \leq G$ that we want to equal its closure, we need to ensure that $\forall g \in G, \forall k \in K, k^{-1} g \in N \implies g \in K$. For this to work, we want $g \in kN \implies g \in K$. Taking $k = e$ forces $N \subset K$, and this is sufficient since $K$ is closed under multiplication.

The upshot is that the subgroups of $G$ equal to their “closures” are precisely the subgroups of $G$ containing $N$. Thus we obtain the correspondence theorem, where images/preimages under $\pi$ form the correspondence.

A Triple Threat

We’ve seen nice descriptions of $f, f^{-1}, f(f^{-1}(-)), f^{-1}(f(-))$. What about strings of length $3$ or higher? It turns out these actually collapse - we have the equalities:

$f(f^{-1}(f(A))) = f(A)$, and $f^{-1}(f(f^{-1}(B))) = f^{-1}(B)$

Here’s one way to see why:

- $f(f^{-1}(f(A)))$ is $f$ applied to the “closure” of $A$, so we know that $f(A) \subset f(f^{-1}(f(A)))$. But it’s also the interior of $f(A)$, meaning $f(f^{-1}(f(A))) \subset f(A)$. Since we have inclusions both ways, we obtain an equality.

- Similarly, $f^{-1}(f(f^{-1}(B)))$ is the closure of $f^{-1}(B)$, so we know that $f^{-1}(B) \subset f^{-1}(f(f^{-1}(B)))$. But it’s also $f^{-1}$ applied to the interior of $B$, so that $f^{-1}(f(f^{-1}(B))) \subset f^{-1}(B)$. Again, since we have inclusions both ways, we obtain an equality.

Images and Subset Operations

Let’s see if we can use this to show why direct image preserves unions. We want $f(A \cup A’) = f(A) \cup f(A’)$. It turns out that, in the spirit of universal properties, it’ll be easier to show these subsets do the same thing, in terms of how they relate to other subsets - we’ll then be able to conclude the equality. Specifically, we’ll show:

$f(A \cup A’) \subset Z \iff f(A) \cup f(A’) \subset Z$

The equality then follows from “following the identity” on each side, by setting $Z = f(A \cup A’)$ and then $Z = f(A) \cup f(A’)$ in turn. Here’s how it’s done:

- $f(A \cup A’) \subset Z \iff A \cup A’ \subset f^{-1}(Z)$, using the universal property of direct image.

- $A \cup A’ \subset f^{-1}(Z) \iff A \subset f^{-1}(Z) \text{ and } A’ \subset f^{-1}(Z)$, using the “packaging” property of unions, which we saw in Products, Categorically.

- $A \subset f^{-1}(Z) \text{ and } A’ \subset f^{-1}(Z) \iff f(A) \subset Z \text{ and } f(A’) \subset Z$, using the universal property of direct image.

- $f(A) \subset Z \text{ and } f(A’) \subset Z \iff f(A) \cup f(A’) \subset Z$, using the packaging property of union.

This argument worked because both direct image and union have a nice description of their supersets. On the other hand, we only have a nice description of subsets of an intersection, so this doesn’t follow through for showing $f(A \cap A’) = f(A) \cap f(A’)$ - indeed, this is false in general. We can package the relations $f(A \cap A’) \subset f(A)$ and $f(A \cap A’) \subset f(A’)$ into $f(A \cap A’) \subset f(A) \cap f(A’)$, though, so at least this holds in general.

In fact, the failure of the equality $f(A \cap A’) = f(A) \cap f(A’)$ implies that we can’t find a “pseudo-inverse” for direct image, in the following sense. Suppose there was some other operation $f^\sharp$ such that $B \subset f(A) \iff f^\sharp(B) \subset A$. Then we could run the following argument:

- $Z \subset f(A \cap A’) \iff f^\sharp(Z) \subset A \cap A’$

- Then, $f^\sharp(Z) \subset A \cap A’ \iff f^\sharp(Z) \subset A \text{ and } f^\sharp(Z) \subset A’$, using the “packaging” property of intersection.

- $f^\sharp(Z) \subset A \text{ and } f^\sharp(Z) \subset A’ \iff Z \subset f(A) \text{ and } Z \subset f(A’)$.

- $Z \subset f(A) \text{ and } Z \subset f(A’) \iff Z \subset f(A) \cap f(A’)$, using the “packaging” property of intersection.

This would then imply $f(A \cap A’) = f(A) \cap f(A’)$, which is false in general. It is true when $f$ is injective, though, by a direct argument, and injectivity is necessary by taking $A, A’$ to be singletons.

When would such an $f^\sharp$ exist? Certainly $f$ would need to be injective. Taking $A = X$, we need $B \subset f(X) \iff f^\sharp(B) \subset X$. But the latter is always true, so we’d need $B \subset f(X)$ to hold for every subset of $Y$. In particular, it holds for $Y$, meaning $f(X) = Y$, so $f$ would need to be surjective. Thus, such an $f^\sharp$ exists only when $f$ is bijective, in which case one can take the direct image along $f^{-1}$.

Direct Image of a Predicate

So far we’ve focused on subsets, since it’s unclear how to interpret “direct image” for predicates. We can adopt the strategy from the previous article, by converting a predicate to a subset, taking the direct image, and then converting back to a predicate.

Let’s start with a predicate \(\varphi : X \to \{0, 1\}\), and a function $f : X \to Y$. We can form the subset $A \subset X$ defined by \(A = \{x \in X \mid \varphi(x) = 1\} = \varphi^{-1}(1)\). Then we take the direct image $f(A) \subset Y$. Finally, we take the membership predicate, to obtain:

$y \in f(A) \iff \exists x \in A, f(x) = y \iff \exists x \in f^{-1}(y), x \in A \iff \exists x \in f^{-1}(y), \varphi(x) = 1$

This, then, is the “direct image” of $\varphi$. We get a new predicate \(\psi : Y \to \{0, 1\}\) which, for each $y \in Y$, looks at the fibre $f^{-1}(y)$, and “sums” the truth values of $\varphi$. If there’s any $x \in f^{-1}(y)$ with $\varphi(x) = 1$, then $\psi(y) = 1$, otherwise it’s $0$.

In fact, the standard existential quantifier is a special case of this, by taking \(Y = \{0\}\), a singleton set. In that case every $x \in X$ is in $f^{-1}(0)$, so we get a truth value of $\exists x \in X, \varphi(x) = 1$, viewed as a function \(\{0\} \to \{0, 1\}\). We’ve summed/integrated the truth values of $\varphi$ to produce a single one.

More generally, if we have a projection $\pi_Z : X \times Z \to Z$, then $\exists (x, z) \in \pi^{-1}(z), \varphi(x, z) = 1$ is equivalent to $\exists x \in X, \varphi(x, z) = 1$. Thus, we integrate over the truth values $\varphi(x, z)$ for a fixed $z$ in order to produce the truth value at $z$.

This also suggests a “universal quantification” operation, giving a new predicate \(\alpha : Y \to \{0, 1\}\) defined by $\forall x \in f^{-1}(y), \varphi(x) = 1$. Again, we look at the fibre $f^{-1}(y)$, but this time we “multiply” together all the truth values of $\varphi$. The result is $1$ if and only if every truth value in this fibre is $1$, otherwise we get $0$. Clearly this is different from direct image; this operation is sometimes called the kernel image. As an exercise, try to see what it looks like on subsets!

It’s much rarer to see this in practice, but there’s one application which comes to mind. Suppose $f : M \to N$ is a smooth map between smooth manifolds. We say that $n \in N$ is a regular value if and only if, for every $m \in M$ with $f(m) = n$, $df_m$ is surjective. This is precisely the “universal quantification” operation applied to the predicate \(\varphi : M \to \{0, 1\}\) with $\varphi(m) := (df_m \text{ is surjective})$.

Further Reading

- The concepts we’ve discussed today are a special case of what’s called a galois connection - specifically, direct and inverse image form a monotone galois connection between the posets of subsets of the domain and codomain.

- In turn, this is a special case of the notion of adjoint functor - the fact that direct image preserves unions is then an instance of “left adjoints preserve colimits”.

- The idea of treating quantifiers as adjoints to substitution appears quite a lot in the internal logic of topoi.

- In this article we’ve focused on preimages, since they behave the nicest with respect to subset operations. Direct images don’t behave as well, but they do at least preserve unions. I discuss this more in Subset Images, Categorically