Why Preimages Preserve Subset Operations

Preimages beat Images

Soon after being introduced to sets and functions, you might come across the notion of the image and preimage of a subset. Given a function $f : X \to Y$, the image $f(A)$ of a subset $A \subset X$ is \(\{f(a) \mid a \in A\} = \{y \in Y \mid \exists a \in A, y = f(a)\}\). And the preimage $f^{-1}(B)$ of a subset $B \subset Y$ is \(\{x \in X \mid f(x) \in B\}\).

When I was first introduced to these, they seemed roughly equal in importance; we’ve got a way of turning subsets of $X$ into those of $Y$, and subsets of $Y$ into those of $X$. But, as anyone who’s studied topology knows, preimages seem to be far more common when subsets are involved! Continuous functions are those for which the preimage of an open subset is open, not the image; measurable functions are those for which the preimage of a measurable subset is measurable. The “contravariant” nature of more geometry-flavoured fields is one aspect that distinguishes them from more algebra-flavoured areas, where we’re concerned with preservation of algebraic operations by homomorphisms in the forward direction.

One reason for this is that preimages turn out to play much better with subset operations than direct images. $f^{-1}(A \cup B) = f^{-1}(A) \cup f^{-1}(B)$ and $f^{-1}(A \cap B) = f^{-1}(A) \cap f^{-1}(B)$, so preimages preserve both unions and intersections. Direct images do preserve unions, but in general $f(A \cap B) \subset f(A) \cap f(B)$, and we don’t have an equality. Personally, though, I found the usual “symbol-chasing” proofs of these statements to be unilluminating; they told me that preimage preserved subset operations, but I still wasn’t clear on why preimage did so.

That’s the subject of today’s article! Using ideas from category theory, we’ll understand why preimage is a particularly “natural” operation to consider on subsets, and also discover a single uniform proof that preimage preserves any subset operation.

Preimage as Substitution

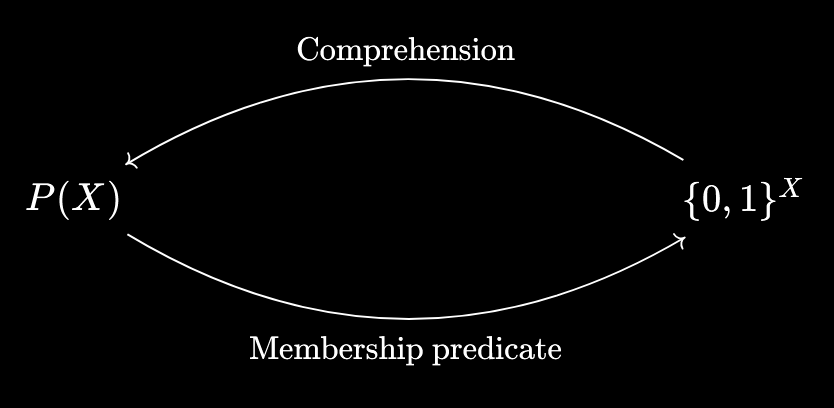

As I mentioned in my Indexed-Fibred Duality article, an alternative way to think of subsets of a set $X$ is as predicates on $X$. Namely, given a subset $S \subset X$, we can form the predicate $\varphi(x) := (x \in S)$ as a map \(\varphi : X \to \{0, 1\}\), where $0$ represents “false” and $1$ represents “true”. Conversely, given a predicate \(\psi : X \to \{0, 1\}\), we can form the subset \(A = \{x \in X \mid \psi(x) = 1\} = \psi^{-1}(\{1\})\). These operations are mutual inverses of each other, which we may represent diagrammatically:

Here $P(X)$ is the powerset of $X$, so the collection of subsets of $X$, while \(\{0, 1\}^X\) is the set of functions \(X \to \{0, 1\}\), i.e. predicates on $X$.

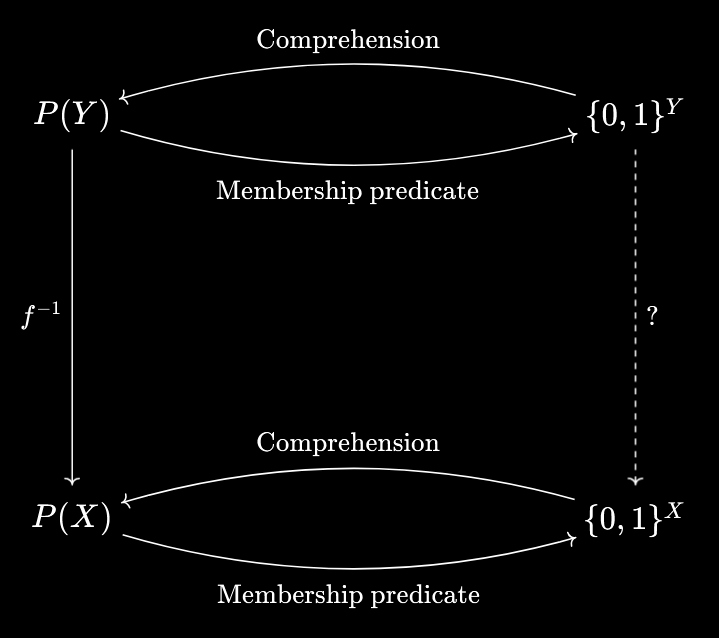

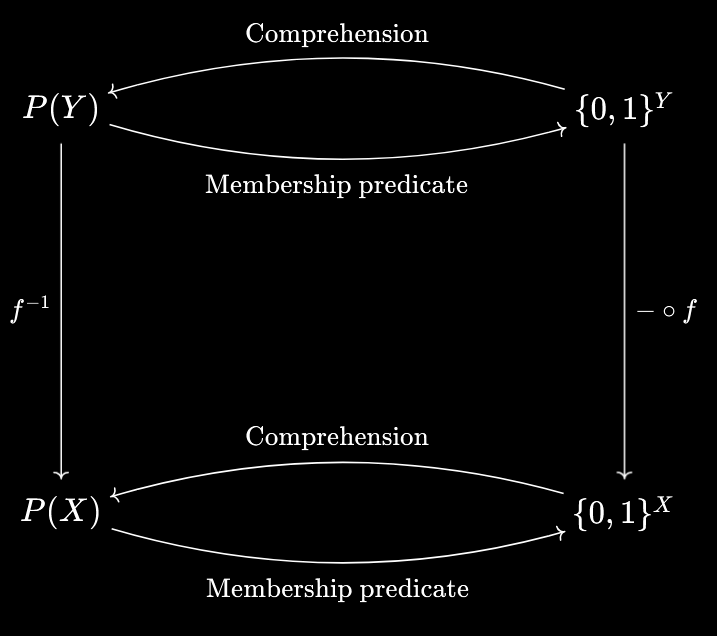

Now, if we’ve got a function $f : X \to Y$, we get a preimage map $f^{-1} : P(Y) \to P(X)$. So one question to ask is - what does this map look like in predicate-world?

The diagram gives us a strategy for determining this. We start with a predicate \(\alpha : Y \to \{0, 1\}\). Then, we comprehend it to get \(S = \{y \in Y \mid \alpha(y) = 1\}\) as a subset of $Y$. Then, we take the preimage under $f$ to obtain \(f^{-1}(S) = \{x \in X \mid f(x) \in S\} = \{x \in X \mid \alpha(f(x)) = 1\}\). Finally, we take the membership predicate \(\beta : X \to \{0, 1\}\) defined by $\beta(x) := (x \in f^{-1}(S))$.

Now, $\beta(x) = 1$ if and only if $x \in f^{-1}(S)$, which is if and only if $\alpha(f(x)) = 1$. So in fact, we have a much simpler expression for $\beta$ - it is just $\alpha \circ f$!

So, in predicate-world, preimage just takes the form of function composition. We have $f : X \to Y$ and \(\alpha : Y \to \{0, 1\}\), so we just compose these to get \(\alpha \circ f : X \to \{0, 1\}\). In some sense, the reason why preimage is such a natural operation on subsets is that it’s natural on predicates - given the predicate $\alpha(y)$, we substitute $y = f(x)$ to obtain a new predicate $\alpha(f(x)) = (\alpha \circ f)(x)$.

Packaging Predicates

Ok, preimage can equivalently be viewed as pure function composition. But how does that help us show it commutes with subset operations? To do that, we’ll also need to transport subset operations into predicate-world.

Let’s start with the unary operation of taking complements. Given a subset $A \subset X$, the complement $A^c$ is defined to be \(\{x \in X \mid x \not \in A\}\). From this, we can see that the corresponding operation on predicates is “NOT”. So, given a predicate \(\varphi : X \to \{0, 1\}\), we obtain a new predicate \(\neg \varphi : X \to \{0, 1\}\) defined by \(\neg \varphi(x) = \begin{cases} 1 \text{ if } \varphi(x) = 0 \\ 0 \text{ otherwise } \end{cases}\).

Again, we can view this simply as function composition. If we define \(\text{NOT} : \{0, 1\} \to \{0, 1\}\) by $\text{NOT}(0) = 1$ and $\text{NOT}(1) = 0$, then $\neg \varphi = \text{NOT} \circ \varphi$.

So, how do we interpret the equality $f^{-1}(A^c) = [f^{-1}(A)]^c$ in predicate-world, given a map $f : Z \to X$? Well, preimage is precomposition with $f$, and complementation is postcomposition with $\text{NOT}$. So, it becomes $(\text{NOT} \circ \varphi) \circ f = \text{NOT} \circ (\varphi \circ f)$. But that’s just associativity! In other words, associativity tells us that the operations of precomposition and postcomposition are completely orthogonal/independent processes - the order in which we do them doesn’t matter. And since complementation can be viewed as postcomposition, while preimage can be viewed as precomposition, they necessarily commute with each other.

This gives us a strategy for providing a “uniform” proof that preimage preserves every subset operation. We convert our subsets into predicates, so that subset operations become logical operations; $\text{AND}$ is a map \(\text{AND} : \{0, 1\}^2 \to \{0, 1\}\), as is every other binary logical operation. Then taking the subset operation corresponds to postcomposition with the logical operation, while taking the preimage corresponds to precomposition with $f$. So these commute because of associativity!

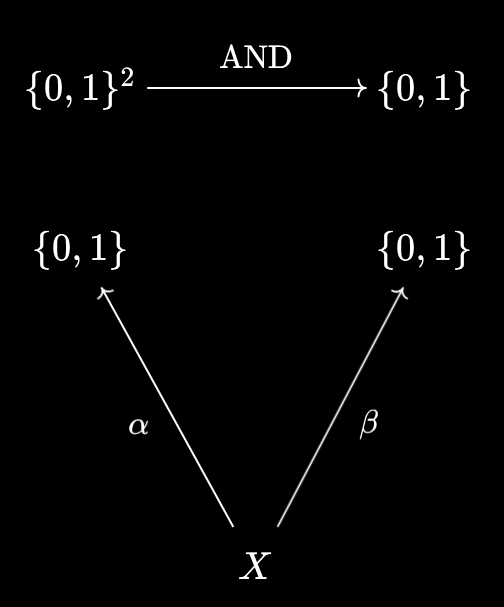

This is… almost correct, but we’re missing a crucial piece of the puzzle. Let’s try showing that $f^{-1}(A \cap B) = f^{-1}(A) \cap f^{-1}(B)$ explicitly to see the issue. We start by converting to their membership predicates \(\alpha, \beta : X \to \{0, 1\}\). However, it doesn’t seem like we can “stick” these together with $\text{AND}$ just yet…

The title of this subsection provides the answer - we first need to package the pair of predicates into a single \((\alpha, \beta) : X \to \{0, 1\}^2\). Only then can we apply $\text{AND}$ to form the predicate $(\alpha \land \beta)(x) := \text{AND}(\alpha(x), \beta(x))$.

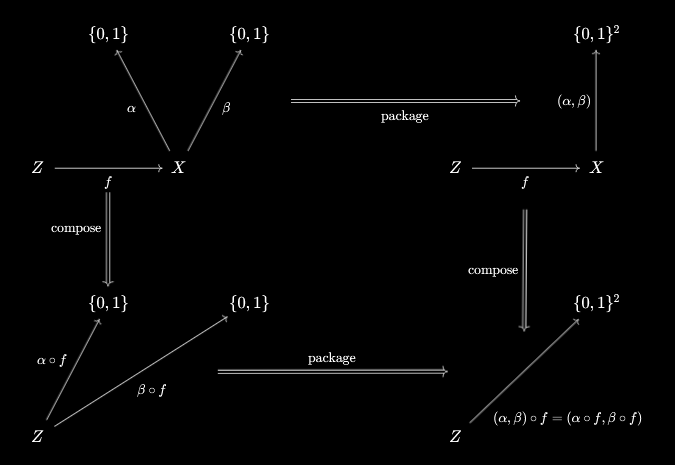

So, in order to apply the argument above, we need to show that packaging is also an orthogonal/independent process to precomposition. Explicitly, for any $f : Z \to X$, we need $(\alpha \circ f, \beta \circ f) = (\alpha, \beta) \circ f$ as functions \(Z \to \{0, 1\}\):

It doesn’t matter if we first package and then compose, or compose and then package, is what we need to verify. For this, we can use the definition of function equality. For any $z \in Z$, we have \([(\alpha, \beta) \circ f](z) := (\alpha, \beta)(f(z)) := (\alpha(f(z)), \beta(f(z)))\) using the definitions of function composition and packaging. On the other hand, $(\alpha \circ f, \beta \circ f)(z) := ((\alpha \circ f)(z), (\beta \circ f)(z)) := (\alpha(f(z)), \beta(f(z)))$ using these definitions. And these expressions are equal! Thus, \(\forall z \in Z, (\alpha \circ f, \beta \circ f)(z) = [(\alpha, \beta) \circ f](z)\), which establishes the equality $(\alpha \circ f, \beta \circ f) = (\alpha, \beta) \circ f$.

Now we can properly complete the proof of $f^{-1}(A \cap B) = f^{-1}(A) \cap f^{-1}(B)$. In predicate-world, we need $(\text{AND} \circ (\alpha, \beta)) \circ f = \text{AND} \circ (\alpha \circ f, \beta \circ f)$. But since packaging is orthgonal to/independent of precomposition, the expression on the RHS is equal to $\text{AND} \circ ((\alpha, \beta) \circ f)$, and we’ve reduced the equality to associativity!

Finally, we have a uniform proof that preimage commutes with any subset operation you can think of - union, intersection, complement, set difference, symmetric difference, indexed union, indexed intersection… all of them. The strategy is:

- Encode the subsets as predicates.

- Encode the subset operation as a logical operation, so a map \(\{0, 1\}^J \to \{0, 1\}\) for $J$ the “arity” of the operation. For complementation we had $J = 1$, and for intersection we had $J = 2$. This also takes care of the case of indexed unions like $\bigcap_{j \in J} A_j$, where $J$ is now an index set.

- Then, preimage preserves this subset operation since preimage takes the form of precomposition, while the subset operation takes the form of packaging and postcomposition, both of which are orthogonal to/independent of precomposition.

To me, at least, this provides a satisfactory answer as to why preimage plays so nicely with all subset operations!

Closing Thoughts

When I’ve searched up this question before, the usual category-theoretic response I’ve seen is to appeal to the notion of adjoint functors. Specifically, it turns out that preimage has both a left and right adjoint, and so preserves both limits and colimits. This ensures it preserves intersections and unions respectively.

While I used to like that answer, I found it unsatisfying that it didn’t explain why preimage preserved other subset operations like complements, or symmetric differences. It seemed like I still had to do a “manual” proof for these, which felt unenlightening.

I figured out this alternative perspective a while ago, in terms of packaging predicates, and these days I much prefer it to the adjoint explanation. Preimage being precomposition and subset operations being postcomposition feels like it gives a much stronger reason why the preservation result is true, without needing to appeal to the machinery of adjunctions. These are still useful for showing that, for example, direct image preserves unions. But I hope you’ll agree with me that the “packaging” explanation is both easier than the symbol-chasing proofs, and more conceptually satisfying!